Fenway Park (36 page)

Authors: John Powers

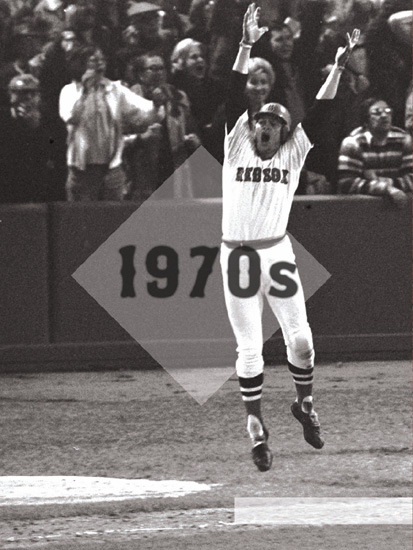

It is one of the most famous images in all of sports: Carlton Fisk willing (and waving) his fly ball to stay fair for a walk-off home run in Game 6 of the 1975 World Series.

B

y the time the 1970s began, a new attitude pervaded baseball in Boston. Smiley faces were everywhere, and not just on those ubiquitous T-shirts. Fans no longer hoped for a team that could play meaningful games after the Fourth of July, they had suddenly come to expect it. In the 1970s—through Vietnam, Watergate, the oil embargo, and the Bicentennial—the Red Sox had a winning record every season, extending their streak of consecutive winning seasons that began in 1967 to 13 by the end of the decade (then ultimately to 16—the most in their history). With that success, however, came seemingly inevitable heartache. They performed heroically in a World Series that many proclaimed the best ever played, which helped to take Bostonians’ minds off divisive court-ordered school busing. However, the Sox lost in the ninth inning of Game 7 on a bloop single to what many considered one of the best teams ever assembled, the 1975 Cincinnati Reds. Fenway got a facelift after that series, as an electronic message board—a first for baseball—and a padded, resurfaced left-field wall debuted in 1976. Two years later, the Sox seemed poised to run away with a pennant, only to have it all come crashing down in the most wrenching fashion. Getting 99 wins in the regular season—their second-highest victory total in 63 years—only got them into a one-game playoff with the Yankees at Fenway, where they lost by a run with the tying man on third in the bottom of the ninth. The Green Monster, which had given them so much during a teamrecord display of home–run hitting the previous year, took from them this time, in the form of a seeming pop fly ball by a light-hitting shortstop. The sage who had spray-painted “No hope!” in foot-high letters across the street from the ballpark in late September 1978 had been right, but barely.

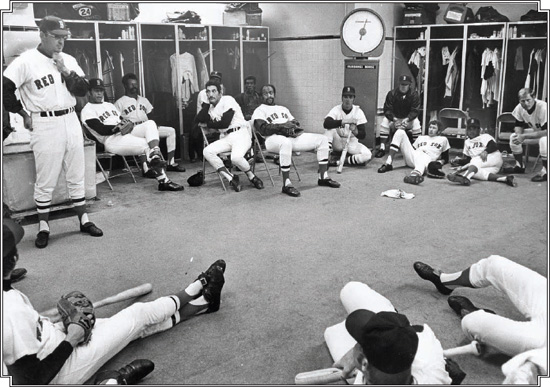

Manager Eddie Kasko had a few words for his team in the clubhouse on April 5, 1973.

A

fter his vocal and volatile predecessor, the bespectacled Eddie Kasko seemed decidedly buttoned-down and dialed-back. But the new Red Sox manager was not averse to the occasional outburst if provoked. “I’ve been known to throw furniture around,” he said. Since most of the key members of the 1967 squad still were in place, the clubhouse mood was optimistic going into the 1970 season. “We’ll win the pennant,” Carl Yastrzemski declared during spring training.

They did win the opener at New York. But the Sox never spent another day in first place. After they went 9-17 in May, they were stuck in fifth. The low point came on June 25 when the club lost, 13-8, to Baltimore in 14 innings at home, despite having led, 7-0. They gave up six runs with none out in the final inning. Before long even Yastrzemski, the team’s only All-Star starter, was being booed at Fenway.

Kasko’s Mr. Chips mien was fraying, too. One day in Anaheim, he stormed into the press box after the organist had played “Tiptoe Through the Tulips” during one of his mound visits.

“We need players,” general manager Dick O’Connell told Tom Yawkey in the press room one August evening when the Sox were stuck in fourth. “We’ve only got eight players.”

“We do?” the owner replied. “Who are they?”

After Boston finished almost exactly as it had in 1969—21 games behind in third place, with an 87-75 record—changes were inevitable. The most startling was a trade that sent Tony Conigliaro, who had led the team in RBI the previous season, to the Angels for three players. “Honest, I never thought I’d be traded. [I thought] that being a hometown boy meant something,” said Conigliaro, who’d spent all of his previous seven major-league seasons in Boston.

Mike Andrews was shipped out, too, dealt to the White Sox for Luis Aparicio. “The fans want a winner and I think we’ve got one now,” Kasko declared before the 1971 season. The club was in first place by the end of April, and won 13 of 15 in late April and early May, putting them up by four games. But the Memorial Day weekend was followed by a slump in which they dropped 11 of their next 14 outings to fall five games off the pace. A lifeless 6-1 loss at New York in early June prompted Kasko to close the clubhouse door and upbraid his underperforming crew. “I’m sick of watching guys hang their heads around here just because we’re in a rut,” he barked.

A vendor sold popcorn and ice cream on Van Ness Street outside Fenway Park in August 1974.

THE SPACEMAN COMETH

William Francis Lee once told Bowie Kuhn, the commissioner of baseball, that he sprinkled marijuana on his pancakes. Lee was an outspoken nonconformist who famously called his Red Sox manager, Don Zimmer, a gerbil. He jogged five miles to the park on the days he was scheduled to pitch, and he once staged a 24-hour walkout when the Red Sox released friend and teammate Bernie Carbo. He said, “Baseball’s a very simple game. All you have to do is sit on your butt, spit tobacco, and nod at the stupid things your manager says.”

Lee also won 119 games over his 13-year career, appearing in the most games ever by a Sox left-hander (321), and recording the third-most victories (94) by a Sox lefty.

Lee won 17 games in three consecutive seasons for the Red Sox and started two games in the 1975 World Series. Lee’s loathing for the Yankees endeared him to Sox fans. In 1976, a collision at home plate resulted in a bench-clearing brawl and Yankee third baseman Graig Nettles threw Lee to the ground in the melee. After the game, Lee called Yankee manager Billy Martin “a Nazi” and the team “Steinbrenner’s Brown Shirts.” Lee missed two months with torn ligaments in his shoulder.

For much of his time in Boston, Lee also feuded with Zimmer, as Lee’s attitude and lack of respect for authority clashed with Zimmer’s old-school personality. Zimmer relegated Lee to the bullpen, and at the end of 1978, the Sox traded Lee to the Montreal Expos for Stan Papi, a utility infielder. The furious Lee bade farewell to the Red Sox by saying, “Who wants to be with a team that will go down in history alongside the ‘64 Phillies and the ‘67 Arabs?” Lee went on to win 16 games for the Expos in 1979, but the team tired of his antics as well, releasing him in 1982 after he staged a one-game walkout over the release of infielder Rodney Scott.

As

Globe

columnist Ray Fitzgerald once said, “He marches to a drummer no one else would let into the ballpark.”

As for himself, Lee said he was either long before or long after his time. He tried to keep the game in perspective. “I think about the cosmic snowball theory,” Lee explained. “A few million years from now, the sun will burn out and lose its gravitational pull. The earth will turn into a giant snowball and be hurled through space. When that happens it won’t matter if I get this guy out.”

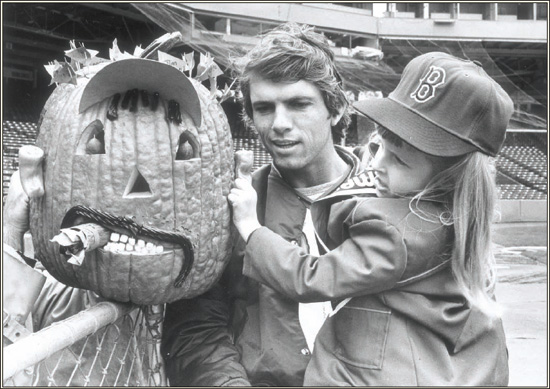

Bill Lee and young fan Tammy Patterson surveyed a pumpkin carved in the likeness of Luis Tiant.

Still, the Sox lost to the Royals for the fifth straight time in mid-June, and slipped into third place. They never regained the lead, finishing 18 games behind Baltimore. That gave management the green light to clean house and by the time the team convened for spring training in 1972, only four players remained from the Impossible Dream team.

The biggest part of the exodus came with a 10-player deal that sent six Boston players, most notably Jim Lonborg and George Scott and Billy Conigliaro (younger brother to Tony), to Milwaukee. “I’m sick of listening to some of those people,” said general manager Dick O’Connell, who’d been annoyed by clubhouse grumbling.

When the season started, Tommy Harper was in center, Danny Cater at first and imposing rookie Carlton Fisk behind the plate. It took until late summer for the new group to coalesce and after losing 10 of their first 14 games, the Sox were buried in fourth place and had slipped to fifth as June was coming to an end. But as the pitching improved with Luis Tiant and Marty Pattin, Boston won 19 of its next 25, including a dozen in a row at Fenway.

The midsummer run peaked with two extra-inning home victories over the Athletics, both wins coming from Oakland miscues. After A’s skipper Dick Williams intentionally (and inexplicably) had Doug Griffin walked to load the bases in the 11

th

inning so that Darold Knowles could face Yastrzemski, his pitcher walked in the winning run to give Boston a doubleheader sweep. The next night, with 1967 notable Gary Waslewski on the mound for Oakland in the 14

th

inning, Yastrzemski bounced a grounder off the glove of A’s third baseman Sal Bando to score Griffin from first base.

By Labor Day, the Sox had taken over first place, beating the Yankees, 10-4, on three-run homers by Harper and Rico Petrocelli as the fans chanted “We’re Number One!” The season came down to a three-game series on the final weekend in Detroit after the Tigers had swept the Brewers (bashing ex-Sox Lonborg in the opener). “I wish the Red Sox a lot of luck and hope they win,” said former Sox team-mate Joe Lahoud after Detroit had run up a 30-10 aggregate on Milwaukee over three games. “But God help them.”