Fenway Park (34 page)

Authors: John Powers

The annual Bat Day promotion at Fenway Park was just one more reason to love 1967.

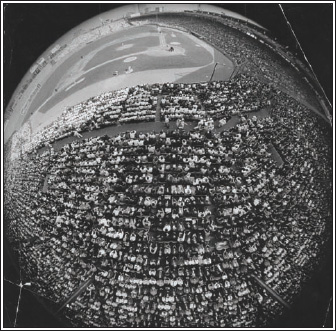

October ’67, as seen through a fish-eye lens.

For one terrifying moment on August 18 at Fenway, when Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton hit Tony Conigliaro in the face with a fastball that left him motionless in the dirt, the magic vanished. “I thought I was going to die,” said Conigliaro, who suffered a fractured cheekbone, a dislocated jaw, and a damaged retina that prevented him from playing again until 1969. “Death was constantly on my mind.”

Yet his shaken teammates won, 12-11, that night and swept the Sunday doubleheader, coming from eight runs down to claim the nightcap, 9-8. From then until the end of the season, Boston was never more than a game out of the lead. “We were doing the impossible,” said Petrocelli, “and we were doing it together.”

It was the Impossible Dream, a quixotic adventure that swept up all of New England in its giddy unlikelihood. No ball club ever had come from ninth place to finish first in one season. But as Boston remained in contention into September, the possibility created both anticipation and anxiety. “I can remember people saying, ‘How can you stand the pressure?’” said Yastrzemski, who found himself on the cover of

Life

magazine. “I’d say, ‘Pressure? This is fun. This is what the game is about.’”

“The Yaz Song,” radio humorist Jess Cain’s ditty, became the summer’s refrain as the slugger defied the game’s laws of probability. “I was in the zone,” Yaz recalled decades later. “You usually stay in it for 10 days, but I was in it for a month.”

As the season came down to its final week, the Sox still were very much in the chase with Minnesota, Detroit, and Chicago. The standings shuffled by the hour. “You were in first place or fourth, depending on the time of day,” said Williams.

Scoreboard-watching became an obsession, particularly in the home dugout. “At Fenway we had the best way of keeping score—the guy in the Wall,” ace pitcher Jim Lonborg noted. “You would see that number disappear and wait for the next one to come up. It wasn’t like it was being blurted out on a Jumbotron.”

Even the improbable numbers worked for Boston in the last few days. After the club was beaten, 6-3 and 6-0, by Cleveland at home, the players figured they were out of the race. “We thought it was over,” conceded Yastrzemski. “Everyone was saying, ‘Well, we had a great year.’”

But when the Twins lost at home to the Angels that same day and the Athletics swept the White Sox in a doubleheader, the Red Sox realized they were still alive, tied with the Tigers and only a game behind Minnesota, with the Twins coming to town for the final two games. “We got up the next morning and said, ‘You know, we still have a chance,’” Yastrzemski said.

What the hosts needed was for Detroit to lose two of its four at home to the Angels while Boston took both games from a Minnesota club that had beaten them in 11 of 16 meetings and that had aces Jim Kaat and Dean Chance scheduled to pitch. The Sox won the first meeting, 6-4, on a three-run homer by Yastrzemski, and then pinned their hopes on the gentlemanly and scholarly Stanford grad who’d won 21 games for them.

“This is the first big game of my life,” Lonborg mused Saturday evening. “I haven’t seen a big one until tomorrow. Never.” To prepare for it, he borrowed teammate Harrelson’s room at the Sheraton-Boston and fell asleep reading

The Fall of Japan

.

After such an enchanted campaign, it was inconceivable that the finale would be without drama or quirkiness. With his team trailing, 2-0, in the sixth, Lonborg began the comeback with a leadoff bunt that ignited a five-run rally marked by a two-run single by Yastrzemski, two wild pitches, and an error. With victory imminent, Fenway organist John Kiley played “The Night They Invented Champagne” and after Rich Rollins popped up to Petrocelli to end things, Fenway erupted in joyous disbelief. As youngsters tried to scale the backstop screen, the crowd rushed the diamond and hoisted Lonborg atop its shaky shoulders on a hero’s ride, ripping off parts of his uniform for souvenirs.

Since Detroit had won the opener of its doubleheader, the celebration in the clubhouse was exuberant yet restrained as the Sox drank beer and smeared each other with shaving cream. If the Tigers won the nightcap, there would be a one-game playoff at Detroit for the pennant.

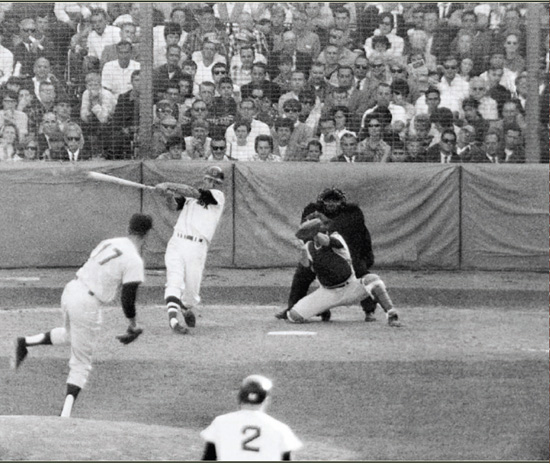

Carl Yastrzemski launched a three-run homer off Minnesota Twins pitcher Jim Merritt in the seventh inning of the penultimate game of the 1967 season. The Sox won their first pennant in 21 years the next day.

YAZ MANAGED TO OUTLAST HIS DREAM SEASON

BY BOB RYAN

“Tris Speaker may have done it, or Duffy Lewis, or some other Red Sox giant of long ago, but Ted Williams didn’t, nor Jimmie Foxx. If any player in baseball history ever had a two-week clutch production to equal Carl Yastrzemski’s, let the historians bring him forth.”

—Harold Kaese

Most baseball careers are measured in years. Carl Yastrzemski’s was measured in epochs. He was in left field the day Roger Maris hit his 61st homer in 1961. He was still playing the day

M*A*S*H

aired its final episode in 1983 (not that there was much chance he had ever heard of Hawkeye Pierce).

No one has ever played as long for one team, and one team only, as Carl Yastrzemski. He is one of the select few with 3,000 hits and 400 home runs. He was handed the thankless task of replacing Ted Williams in left field in 1961, and by the time he retired 22 years later, he had found a way to create his own distinct legend.

But perhaps Yastrzemski’s most significant achievement was that he managed to overcome the bizarre handicap of having that one transcendent season. He could have been Orson Welles, never able to top

Citizen Kane

. He could have been Don McLean, still waiting for the appropriate follow-up to “American Pie.” He could have let 1967 engulf him, but in due time, he allowed it to define him.

1967. If you weren’t there, you’ll just never know. You won’t understand what Boston was like, when every night in June, July, August, and September you could follow every pitch with Ken Coleman and Ned Martin from stoplight to stoplight and front porch to front porch and business to business, because the entire city was recaptured by baseball and the Red Sox, thanks to Yaz and his teammates. Before Yaz won the Triple Crown in 1967, before the Impossible Dream season, you could pretty much have any Fenway seat you wanted at any time.

In 1967, Carl Yastrzemski showed us what grace and determination under athletic pressure could produce, and while he never again had an all-around season like that, neither has anyone else. With his bat, glove, arm, and will, he personified the idea of the Most Valuable Player.

Hyperbole? OK, you judge. In the final 12 games of a sizzling four-team pennant race, Yaz was 23 for 44 (.523), with five homers, 16 RBI, and 14 runs scored. Throw in the Gold Glove Award and underline the 7 for 8 hitting in the final two games of the season, and then put the exclamation point on the performance by throwing out Bob Allison trying to stretch a single to squelch an eighth-inning Minnesota rally on the season’s final day. In the ensuing years, we have not seen a more valuable Most Valuable Player.

Manager Billy Herman told him after the 1966 season, “You can’t be a leader the way you played this year. You can be a great ballplayer if you’ll work at it.”

Yaz hired a Hungarian immigrant fitness trainer named Gene Berde and said, “I’m yours.” No baseball player had ever done such a thing. He reported to training camp with a new body and a new sense of purpose in 1967 to play for Dick Williams, a new, energetic, no-nonsense manager. But as heroic as Yaz was in leading the Sox to the pennant, he could not win the World Series all by himself. He certainly did his part, batting .400 with three home runs, but the Sox lost in seven games to Bob Gibson and the St. Louis Cardinals.

Yaz would go on to have good years, but never anything like 1967. What he did was last long enough at a high enough level to construct a new image, that of the ultimate grinder. His toughness, his consistency, and his unmatched work capacity—along with that unforgettable 1967 campaign—remain his legacy.

So the players waited several more hours, listening to the play-by-play from Michigan. “For us to be sitting around a radio instead of a TV, it reminded me of an old-time movie where you were listening for news of some important event,” Lonborg said. When the Tigers grounded into a double play with the tying run at the plate to complete an 8-5 loss, Williams leaped up. “It’s over, it’s over,” the skipper proclaimed. “It’s unbelievable!”

Now it was time for champagne and tears. “This is the happiest moment of my life,” declared Yawkey as he sipped Great Western from a paper cup, relishing the end of two desiccated decades. “THE SMELL OF THE PENNANT . . . THE ROAR OF THE CROWD” declared the headline on the front page of Monday’s

Globe

.

Just getting to the World Series was such a miracle that few fans had time to ponder the upcoming challenge—the formidable St. Louis Cardinals club of Lou Brock, and Bob Gibson, Curt Flood, and Orlando Cepeda that had won the National League flag by a mile over the San Francisco Giants. Gibson, its glaring ace, had missed nearly two months after his right leg was broken by a line drive in July, but he was overpowering in the opener at Fenway, yielding only a solo homer to counterpart Jose Santiago in the third inning while holding hitless Yastrzemski, Petrocelli, and Harrelson, all of whom took batting practice after the 2-1 loss.

Yastrzemski responded with two homers and four RBI the next day, but his team needed just the bare minimum as Lonborg befuddled the Cardinals, taking a perfect game into the seventh inning and coming within four outs of a no-hitter before Julian Javier smacked a double, in a 5-0 whitewash. “I hope we can end the Series on Monday,” Williams said with brash optimism.

On Monday, though, his club was teetering on the edge of extinction after St. Louis had administered 5-2 and 6-0 tutorials at Busch Stadium. It was left to Lonborg to bring the Sox back home alive and he delivered with a 3-1 decision. “Same lineup, same result,” Williams decreed for the sixth game in Boston. But his pitching choice was startling. Gary Waslewski had started only four games all season and had been sent down twice to the minors.