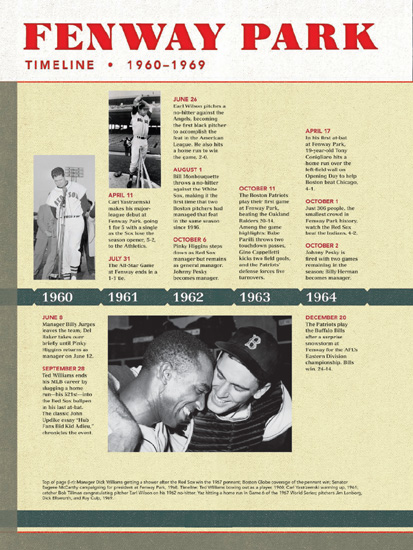

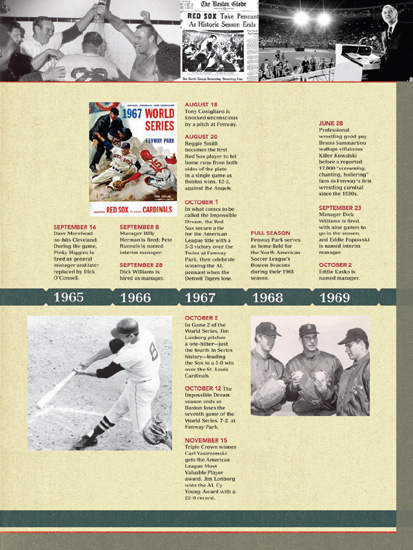

Fenway Park (35 page)

Authors: John Powers

Nobody with that little experience had ever been tapped for a decisive World Series game, but Waslewski performed superbly until the sixth inning and Boston hitters worked over eight St. Louis hurlers. The Sox set a post-season record with three homers in the fourth as Yastrzemski, Reggie Smith, and Petrocelli chased starter Dick Hughes. Boston then broke things up with four more runs in the seventh for an 8-4 triumph.

The outfield wall got a thorough scraping in March 1968.

REMEMBERING TONY C

Mike Higgins, the general manager, thought he was too young. But Johnny Pesky, the manager, had already seen enough of Tony Conigliaro in spring training in Arizona in 1964 to know he had a natural power hitter in camp, and he brought him up to stay at age 19.

On Opening Day at Fenway Park that season, Conigliaro, a year out of St. Mary’s High School of Lynn, Massachusetts, stepped to the plate and in his first at-bat unloaded a home run off White Sox pitcher Joel Horlen.

Conigliaro went on to become the youngest American League player to reach the 100-homer mark, and the youngest ever to lead the majors in homers (with 32 in 1965, at age 20). At the height of his popularity, the handsome, dark-haired Tony C also did a little singing, and he performed on

The Merv Griffin Show

, among other places.

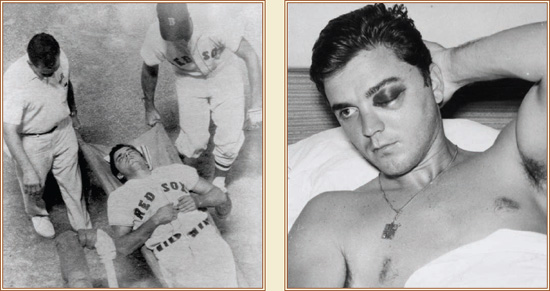

Conigliaro was hitting .287 with 20 homers and 67 RBI in 1967 as the Red Sox chased their first pennant in 21 years. But on Friday, August 18, at Fenway, his life changed forever. Conigliaro “was never one to back off from an inside pitch,” said Pesky, and Tony C was struck in the face by a fastball from Angels pitcher Jack Hamilton.

The ball shattered Conigliaro’s cheekbone and cracked the orbital bone encasing his left eye. The impact also severely damaged the retina of his left eye. The beaning was so severe that Conigliaro dropped to the ground face first, bleeding from the nose and eye.

Later, Conigliaro described the impact: “His first pitch came in tight. I jumped back and my helmet flew off. There was this tremendous ringing noise. I couldn’t stand it. . . . I kept saying to myself, ‘Oh, God, let me breathe.’ I didn’t think about my future in baseball. I just wanted to stay alive.”

Conigliaro sat out the entire 1968 season, and after two comeback attempts, he retired in 1975 at age 30. Teammate Rico Petrocelli remembered the comebacks, the first of which produced a remarkable 36-homer, 116-RBI season in 1970, before Conigliaro was traded to the Angels.

“He wouldn’t quit. He made the greatest comeback, I think, in the history of baseball. He was the most courageous player I ever saw,” said Petrocelli.

Tony C remained a popular figure in Greater Boston, running a nightclub with his brother Billy, who had also played for the Red Sox. While he was being driven to the airport by his brother on January 3, 1982, Conigliaro suffered a massive heart attack; his heart stopped for several minutes, and he suffered a stroke and lapsed into a coma.

Conigliaro remained in a vegetative state until his death on February 24, 1990. He was 45 years old.

The Tony Conigliaro Memorial Award is presented annually by the Boston Baseball Writers Association to the major-league player who has overcome adversity with the spirit and courage demonstrated by Conigliaro.

On August 18, 1967, Tony Conigliaro’s life changed forever when he was struck in the face by a pitch from the Angels’ Jack Hamilton. “Tony C” had led the league in home runs in 1965 with 32, at age 20 the youngest to do so at the time. His injuries from the beaning kept him out of baseball for almost two years, and after two comeback bids, he retired from the game in 1975.

Nuns’ Day, which was a park tradition in the ’60s, brought an added dimension to the term “Fenway faithful.” Boston Archbishop Richard Cardinal Cushing (seated) was often in attendance.

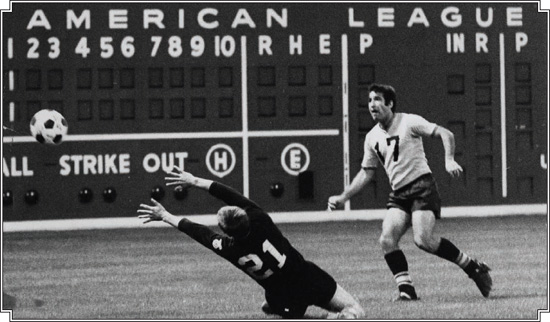

Fenway has played host to lots of soccer matches. In this 1968 contest, Ruben Sosa (17) of the North American Soccer League’s Boston Beacons fired on Chicago Mustangs goalkeeper Gerd Langer.

“Lonborg and champagne,” Williams predicted for the finale even though his ace would be dueling Gibson on two days’ rest. “CINDERELLA TRIES ON THE SLIPPER,” read the

Globe

headline on the morning of Game 7 as all of New England anticipated a fairy-tale finish. “This is a story that has to have a happy ending,” Kaese declared. If the Sox lose “it will be the wolf gobbling up Little Red Riding Hood.”

The wolf licked its chops.

The Sox couldn’t solve Gibson, who struck out 10 and hit a homer off the depleted Lonborg, who departed after six innings with St. Louis leading by six runs. “Lonborg and champagne, hey!” the Cardinals chanted in the clubhouse after they’d claimed their second world championship in four years by a 7-2 count. “Now it’s our turn to pop off,” shouted outfielder Flood as he pried open a bottle of Mumm’s. “Pop this.”

As the club packed for the winter, hundreds of Red Sox fans lingered in their seats, unwilling to let go of the most enthralling season of their lives. “The laurels all are cut, the year draws in the day, and we’ll to the Fens no more,” Roger Angell wrote in his

New Yorker

account.

While the Dead Sox days were over, it would be another eight years before the Sox suited up for a playoff game. Even before the club convened for spring training in 1968, the chances for a reprise had lessened markedly when Lonborg tore up his knee skiing at Lake Tahoe before Christmas. That was the prelude to a procession of problems that sabotaged the season. Lonborg returned, but posted a losing record. Santiago hurt his arm and never won another game. Scott saw his average plummet from .303 to .171 and failed to hit a homer at Fenway. And Conigliaro’s comeback bid ended before it began, undone by blurred vision.

The Sox, who never were in first place after Opening Day, were out of contention by Flag Day. “We’ll win it next year,” declared Yastrzemski, after Boston had finished fourth, 17 games behind the Tigers. “There’s no doubt in my mind about that.”

When Conigliaro smashed a two-run homer and scored the winning run in the 12

th

inning of the opener at Baltimore in 1969, Boston fans saw it as a harbinger of a restoration. But nobody that year was going to catch the Orioles, who won 109 games and claimed the East Division in the first season of baseball’s four-division format. When Boston slipped from second to third in August, player discontent grew with Williams and his whip-hand ways. The friction peaked in Oakland when the skipper yanked Yastrzemski after the first inning for not hustling, bawled him out, and fined him $500.

With nine games to go in the season, Yawkey dumped Williams, who went on to win two championships with Oakland and be enshrined in the Hall of Fame. Memories of the Impossible Dream had been soured by an irremediable dyspepsia. “The days of wine and roses didn’t last long, which should have been predictable,”

Globe

columnist Ray Fitzgerald mused.