Fenway Park (30 page)

Authors: John Powers

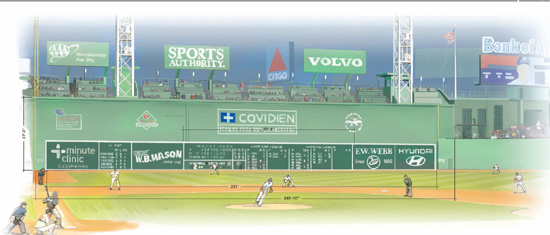

FISK POLE:

The pole on the left-field foul line atop the Green Monster is known as the Fisk Foul Pole, in honor of Carlton Fisk’s game-winning homer that struck the pole in the 12

th

inning of Game 6 of the 1975 World Series.

310:

At the foul pole, the Wall is only 309 feet, 3 inches from home plate, but for most of the century the Red Sox posted a sign that read “315.” Club officials refused to allow an independent measurement of the distance, but when a Boston

Globe

reporter snuck into Fenway and came up with the new figure, the Sox grudgingly changed the sign to read 310 feet in 1995. Major League rules today stipulate that no fence in any new park be closer than 325 feet to home plate.

96:

Metric distances were added to the outfield walls in 1976, when it was thought that the U.S. would adopt the metric system; thus the 315-foot marker had a smaller accompanying 96-meter marking in yellow. The metric figures were painted over during the 2002 season.

THE LADDER:

A ladder runs from above the scoreboard to the top of the Wall. It was once used to retrieve home-run balls, but it is no longer needed with the advent of the Monster seats. A ball is in play if it hits it.

CITGO SIGN:

Every time a player hits a home run over the Green Monster, the CITGO sign is seen by fans at the ballpark and on television. The computer-operated sign is double- faced and measures 60 feet by 60 feet. In early 2005, the sign received a major restoration and technology upgrade from neon light to LEDs.

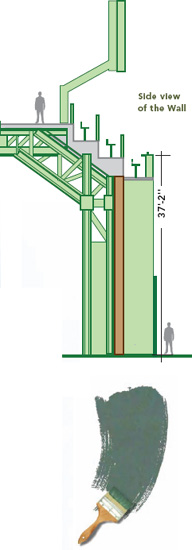

“FENCE GREEN”

The green paint used on the wall is a 100 percent acrylic made by California Paints, which was founded in Cambridge, Mass. in 1926 and is now based in Andover, Mass. The color, called “Fence Green,” is considered proprietary by the Red Sox; it is not sold publicly, and the formula of colorants is a secret. The hue of Fence Green has apparently been the same since the wall was first painted in 1947, although California Paints didn't start producing the color until the 1970s. It takes about 35 gallons of paint to cover the wall. Other green hues are used around Fenway Park, including Scoreboard Green, Box Green, and Special Green.

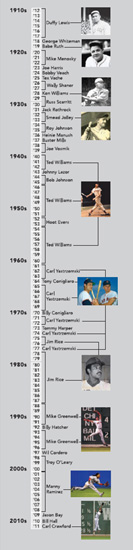

FENWAY’S LEFT FIELDERS

Red Sox players who played most games in left field for each of the last 100 years.

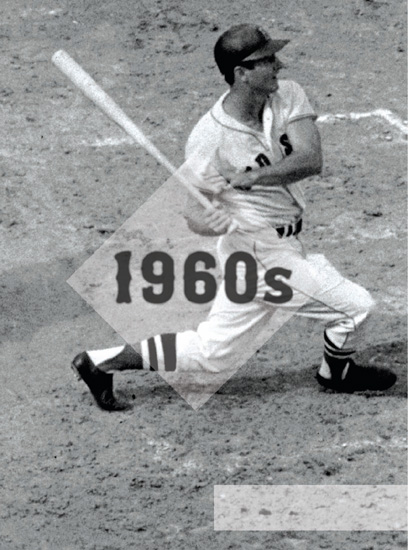

Carl Yastrzemski follows the flight of his second home run of Game 2 of the 1967 World Series, a 5-0 Red Sox victory. Yaz supplanted Ted Williams in left field for the Red Sox and created his own legacy, including an MVP season in ’67 and his stature as the first American League player to have at least 400 home runs and 3,000 hits.

I

n the early 1960s, the fledgling Boston Patriots of the American Football League began playing at Fenway Park. While there would also be soccer games and wrestling matches played at Fenway during the 1960s, what the ballpark didn’t have for the first part of the decade was much of a baseball club. When Ted Williams retired after hitting a home run in his final at-bat in 1960, he took most of the drama surrounding the team with him. The Red Sox weren’t just a boring club, they were also inept. The Sox of the 1960s echoed the franchise’s teams of the 1920s by finishing in the second division for eight straight seasons, including ninth-place finishes in 1965 and 1966. Little wonder that owner Tom Yawkey ceded to the Patriots’ wishes to play in his park, lifting a ban on football at Fenway partly so that he could derive some income from the newcomers, since Sox fans were staying away in droves. The nadir for the Red Sox came on September 28 and September 29 of 1965, with the team en route to a 100-loss season; the attendance for consecutive games was 461 and 409 fans, respectively. The Sox changed things up in 1967, hiring a brash new manager named Dick Williams and giving its young nucleus a chance to play, and to flourish. Everything changed for Boston and the Red Sox in that Summer of Love; while young people throughout the country flush with “Flower Power” were being warned not to trust anyone over 30, New Englanders were learning to count on a man in his late 20s called Yaz. The Sox captured one of the most exciting pennant races in history, jostling past the White Sox, Twins, and Tigers for their first AL title in 21 years. And Boston baseball would never be the same.

UPDIKE HIT IT OUT OF THE PARK, TOO

BY BOB RYAN

On September 28, 1960, John Updike, 28 years old and, though raised in Pennsylvania, a Ted Williams fan since childhood, decided it was a good idea to attend the afternoon game between the Red Sox and Baltimore Orioles. He, like all members of the public, knew only that it would be the final home game of Ted’s career. Not until the game was concluded did people learn that it would be Ted’s last game, period, that he had decided before the game he would not be making a season-ending trip to Yankee Stadium.

The times were different. The word “hype” had barely entered the language. Today, there would be special editions, minted coins, and live shots galore.

“The world was a simpler place,” Updike noted.

But Wednesday, September 28, 1960, was a dank, dreary day. And the Red Sox, Ted Williams aside, were a dank, dreary team on their way to a 65-89 record and a seventh-place finish. Accordingly, a mere 10,454 fans showed up. And it could very easily have been 10,453. Updike’s first choice that day was to visit a lady on Beacon Hill. Fortunately, the lady was not home.

Updike explained in a 1977 epilogue: “I took a taxi to Beacon Hill and knocked on a door and there was nothing, just a basket for mail hung on the door. So I went, as promised, to the game and my virtue was rewarded.”

The resulting “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu,” published in the October 22, 1960 edition of the

New Yorker

, is the most spellbinding essay ever written about baseball. Some, like critic Roger Dean, go even further. “It is simply the greatest essay I have ever read,” he said.

“It influenced me in a big way,” said Roger Angell, who would become the foremost baseball writer of the late 20

th

century, but in 1960 had yet to publish a word about it. “And it has influenced just about every sportswriter who followed. The great thing is that he went expecting something amazing and incredible—and it happened. Only baseball provides in any number those totally unexpected turns.”

“My one effort as a sportswriter,” explained Updike. “It’s had a longer life than I would have expected.”

We all know how the story ends. In the eighth inning, battling horribly adverse weather conditions that had already cost him one shot at a homer, Williams hit a 1-1 pitch from Jack Fisher onto the canopy covering a bench in the Red Sox bullpen. He ran the bases hurriedly amid relentless applause and did not tip his cap. He took his place in left field at the start of the ninth and was replaced by Manager Mike Higgins with Carroll Hardy, in the hopes that Williams would acknowledge the crowd, and again he did not tip his cap. He had not tipped his cap since 1940 and he had no remote intention of deviating from his policy.

Wrote Updike, “No other player visible to my generation concentrated within himself so much of the sport’s poignance, so assiduously refined his natural skills, so constantly brought to the plate that intensity of competence that crowds the throat with joy.”

Williams liked the piece. At least, that’s what was conveyed to Updike by a third party. And Ted even suggested Updike be a collaborator on a biography, an offer that Updike, a longtime resident of Boston’s North Shore who died in 2009, politely declined.

“I’d said all I had to say on the subject,” he said in the epilogue.

Of Ted’s stubborn refusal to tip his cap that day, despite being given three separate opportunities to do so (coming to the plate, rounding the bases, and trotting in after being removed from the field), Updike sagely noted, “Gods do not answer letters.”

But they sometimes leave behind epic accounts of epic events.