Fenway Park (26 page)

Authors: John Powers

Birdie Tebbetts, Mel Parnell, and Vern Stephens posed in the Fenway clubhouse after a game in 1950.

A clubhouse attendant tidied up the home team locker room in ‘53.

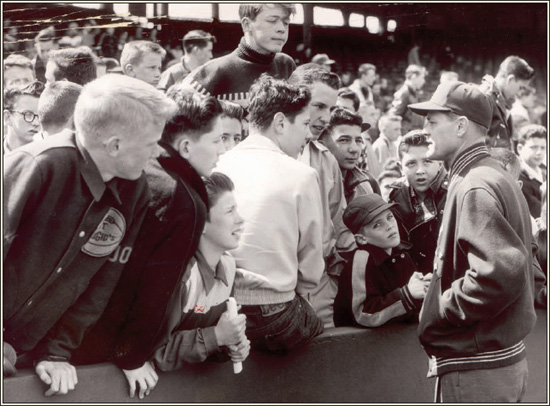

YOUTH BASEBALL CLINICS

Over more than two decades, between 1952 and 1974, tens of thousands of youngsters attended baseball clinics with Red Sox coaches and players at Fenway Park. The clinics—billed as a one-day “spring training” for players from Little League to high school age—were sponsored by the Red Sox and the Boston

Globe

. Said Red Sox General Manager Joe Cronin on the announcement of the inaugural clinic in 1952, “Who knows but someday one of the pupils may be wearing a major-league uniform.”

Indeed, at least two players who attended clinics as high school students went on to become instructors: Bill Monbouquette of Medford and Wilbur Wood of Belmont. In May 1960, Monbouquette threw a one-hit shutout for the Red Sox over the Tigers in front of thousands of youths who had attended a clinic earlier in the day.

The first clinic, in April 1952, featured players from the Red Sox and the Boston Braves, who would leave town a year later for Milwaukee. The event brought an estimated 5,000 young ballplayers and coaches into the park, and they stayed for the fourth game of the exhibition city series between the Red Sox and Braves. The youngsters were treated to a display of new Red Sox skipper Lou Boudreau’s famous pickoff play, and instruction from the Braves’ Tommy Holmes on hitting to the opposite field.

In a

Globe

article promoting the first clinic, Boudreau directed clinic attendees: “If you get your heart set on becoming a Major League Baseball player, nothing will stop you. . . . Don’t shirk your work. No manager likes a loafer. Play hard and for keeps, even if it’s only a practice game.”

Among the players who participated in the youth clinics over the years were Warren Spahn, Dom DiMaggio, Johnny Pesky, Jackie Jensen, Jimmy Piersall, Frank Malzone, Carl Yastrzemski, Tony Conigliaro, George Scott, and Carlton Fisk. In later years, some of the youngsters were brought out to work with the players on the field, and the clinic always concluded with a crowd-pleasing home-run contest.

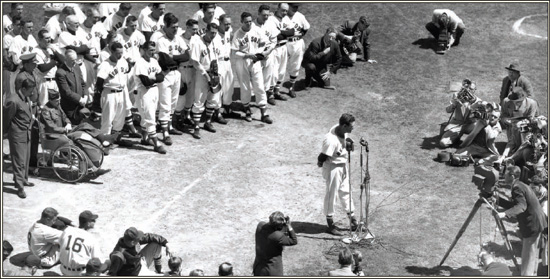

THE KID BIDS ADIEU FOR THE FIRST TIME

In 1960, Ted Williams closed out his career at the age of 42 with a home run in his last at-bat, a moment celebrated by John Updike in his essay, “Hub Fans Bid Kid Adieu.” But more than eight years earlier, Williams had batted for what many then thought would be his final time, on April 30, 1952—the day before he left for active duty as a fighter pilot in the Korean War. Ted was nearly 34 years old, and no one knew how long his military duty would last, or whether he would return.

Williams was brash and outspoken, and he had a tempestuous relationship with the Boston press. But he knew better than to complain when he was called to active military duty in early 1952. In 1941 Williams had been classified 3-A by his draft board, due to the fact that his mother was totally dependent on him. When his classification was changed to 1-A following U.S. entry into World War II, Williams appealed to his draft board, and the board agreed with him. He announced that he intended to enlist once he had built up his mother’s trust fund, but the press and some fans were merciless in their complaints that Williams was ducking his duty. He enlisted in the Navy in 1942, and unlike many wartime ballplayers who played for service teams while in uniform, Williams was awaiting orders as a Marine pilot when the war ended.

Fast-forward to early 1952: Williams was now 33 years old, married with a child, and had not flown in eight years. But the Korean War was raging and he was called to active duty. After completing refresher training, he returned to the military service that would cost him almost five seasons of his career and very nearly take his life. He flew 39 combat missions over Korea, including one that ended in a crash landing and escape from the flaming wreckage of his crippled aircraft after it was hit by enemy fire. Soon after that, he contracted pneumonia and developed an inner-ear infection. He was discharged in July 1953.

The pregame stories on that April day in 1952 called it Williams’s Fenway farewell, and the Globe’s Jack Barry wrote the following day, “Fittingly climaxing a 14-year career, in what may have been his last appearance at bat . . .”

The Red Sox had declared it “Ted Williams Day” and the 24,764 fans, the Tigers players, and Ted’s teammates joined hands and sang “Auld Lang Syne” during a pregame ceremony in which Williams received a new Cadillac. A day later, he would report to Willow Grove, Pennsylvania, for training, but not before putting an exclamation point on his career to that point.

The Red Sox and Tigers were tied, 3-3, in the bottom of the seventh inning when Teddy Ballgame came to the plate. Barry wrote, “In this most dramatic and tense moment, with every fan in the ballpark cognizant of what Williams has done under pressure in the past, the amazing Kid delivered.”

Williams ripped a curveball from the Tigers’ Dizzy Trout eight rows deep into the right-field grandstand. It was his 324

th

career homer.

After the game, former teammate Rick Ferrell, then a coach with the opposing Detroit Tigers, speculated that Williams could come back, even if he missed two seasons, because “he keeps in great shape.”

Although Williams would miss nearly all of the next two seasons, he would return to hit nearly 200 more home runs. And before his third and final “curtain call” at-bat in 1960, he had a second one. In April 1954, Williams told the

Saturday Evening Post

that the coming season would be his last, as most of his contemporaries had retired and the team was emphasizing its younger players. On September 26, in the season’s final game, Williams came up in the seventh inning and homered into the right-field stands. However, the Sox batted around and he came up again in the eighth, this time popping out. Sure enough, after the game he confirmed his plan to retire, saying, “That’s it.”

But by May of 1955, he was back again, returning for six more seasons and a final adieu.

But the Browns were convinced that the zany provocateur was unbalanced. “Want to know something? I believe that man’s plumb crazy,” said catcher Clint Courtney. “Yuh, he’s nuts altogether.” A few weeks earlier, Piersall had brawled in the dugout at Fenway with Billy Martin, the Yankees’ own time bomb. Sox Manager Lou Boudreau worried that Piersall was becoming unhinged and forbade photographers to take posed photos of him without the skipper’s consent.

By the end of the month, the club had sent Piersall to its minor-league team in Birmingham, where his erratic behavior continued. “He just got worse every day,” Cronin observed. A month later, Piersall was being treated in a Massachusetts hospital for what was described as nervous exhaustion, but, in fact, was mental illness. He recovered, returned the next season and played six more in Boston and 15 more years in the majors. But his teammates faded without him during the 1952 stretch run, losing 20 of 27 games in September and finishing sixth, 19 games behind the Yankees.

That was enough for the front office, which decided to go with bonus babies in 1953. Except for Williams, who was on sabbatical above the 38

th

parallel, the 1946 pennant winners were gone. Doerr had retired after the 1951 season and Johnny Pesky had been dealt to Detroit. When Boudreau elected to go with rookie Tom Umphlett in center, Dom DiMaggio called it a career in early May after playing only three games that season. “After all the good years I’ve had,” said the 36-year-old, “I’m not going to be sitting on the bench.”

Boston had finished in the second division for the first time since the war, attendance had dropped by nearly a half-million in three years and the Yankees had won four more rings. Investing in the past was a losing proposition, Yawkey concluded. “We take the long view,” said Boudreau. “We can’t expect to be a pennant contender for at least two years.”

Yet the “Green Sox”—the league’s youngest bunch in 1953—still managed to be entertaining, winning 35 one-run games and clubbing the Tigers by 16 and 20 in a two-day June outburst at Fenway. In the second bashing, Boston rolled up a record 17 runs in the seventh inning alone, batting around twice. “Who made the three outs?” cracked pitcher Skinny Brown in the wake of the 23-3 victory.

Not that the sound-and-light show counted for much. The Sox already were in fourth place, 14 games behind New York, and were still there when Williams returned from Korea at the end of July and promptly whacked a pinch-hit homer against the Indians. “There’s no doubt about it—flying jet planes improves the eyesight,” Yankees Manager Casey Stengel cracked after Williams knocked in four runs during a Labor Day weekend doubleheader at Fenway. “Baseballs now look as big as grapefruits to Williams.”