Fenway Park (21 page)

Authors: John Powers

Several players who had enlisted as naval aviation cadets joined Lt. Cmdr. E.S. Brewer at Fenway Park on April 27, 1943, before the Red Sox-Yankees game. Front row, from left: Johnny Pesky of the Red Sox, Brewer, Buddy Gremp of the Boston Braves, and Joe Coleman of the Philadelphia Athletics. Back row, from left: Ted Williams, and Johnny Sain of the Boston Braves.

FDR’S ROAD SHOW

When U.S. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s motorcade arrived at Fenway Park on the night of November 4, 1944, there wasn’t a bare patch of ground between Kenmore Square and the ballpark, or for blocks around. It was three days before the presidential election, and FDR’s race against Governor Thomas Dewey of New York had taken a nasty turn. Factor in that Roosevelt was preceded on stage by two enormous talents of music and film, and the ballpark and the surrounding neighborhood were rollicking in a boisterous but far different fashion than if the Red Sox were staging a ninth-inning rally.

Sound wagons blared campaign tunes and patriotic songs, and hawkers sold buttons promoting Roosevelt and Maurice J. Tobin, the Democratic candidate for governor of Massachusetts. Inside the park, red, white, and blue bunting and banners were draped along the infield wall, around uprights, and along the edge of the grandstand roof. More than 250 newspaper reporters were instructed by Secret Service men to meet in a garage on Ipswich Street, and they entered the park in columns of three at 8 p.m., an hour ahead of Roosevelt’s entrance.

One of the key questions in voters’ minds was the health of the three-term president, compelling Roosevelt to undertake a whirlwind tour of several cities, including a four-hour appearance in New York City a couple of weeks earlier in bitterly cold temperatures. When he got to Boston on this Saturday night, the estimated 40,000 people inside the park and thousands more outside were treated to opening acts by Frank Sinatra, who sang the national anthem, and writer-director Orson Welles. Just three years removed from Citizen Kane, Welles boomed out an oratory as only he could. “The audience delightedly applauded each at frequent intervals,” wrote

Globe

reporter Leslie G. Ainley.

When FDR’s open car entered the park and he took the stage at the center of the field, the crowd was in a frenzied state. Announcers tried to still the tumult as he began to speak, but audience members continued their roaring welcome until the president himself reminded them in a shout over the loudspeakers that radio time costs money. He spoke for 36 minutes, firing back at charges leveled by Dewey, the Republican candidate, that Roosevelt had sold out to communists. FDR accused his opponent of “a shocking lack of faith in America.”

The

Globe

’s Louis M. Lyons called the appearance “a thundering windup” to FDR’s campaign for reelection and reported that the crowd was “almost delirious in their wild cheering” for him. Just over five months later, after winning an unprecedented fourth term handily, FDR died of a cerebral hemorrhage in Hot Springs, Georgia, on April 12, 1945, at the age of 63. The appearance at Fenway Park turned out to be the final campaign speech of his life.

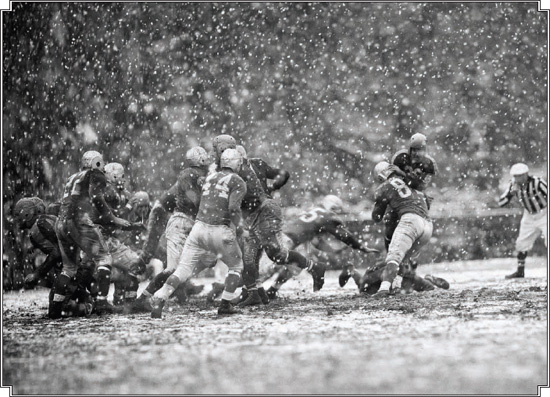

Jack Matheson of the Detroit Lions (right) stopped Johnny Grigas of the Boston Yanks for no gain in the second quarter of a November 4, 1945, game at Fenway Park. The Lions eked out a 10-9 victory in the game played during a heavy snowstorm.

Robinson went on to play in six World Series with the Dodgers and was elected to the Hall of Fame; Jethroe was Rookie of the Year for the Boston Braves. But the Sox didn’t suit up a black player for another 14 years and went on to finish seventh that year, 17½ games behind the Tigers. By then the war had ended and Williams and his fellow veterans would be coming home, ready for a renaissance.

Once their stars had exchanged one uniform for another, the Sox enjoyed a spring flowering in 1946. The return of Williams, DiMaggio, Doerr, and Pesky revitalized the lineup, which was further bolstered by the arrival from Detroit of slugging first baseman Rudy York, who knocked in 119 runs.

Williams, who’d missed three full seasons since enlisting, dramatically announced his return with a homer in his first at-bat against the Braves in spring training. From Opening Day until the season finale, Boston owned the league, spending all but one day in first place. The Sox won their first five games and 21 of 24, including a 15-game streak that began with a 12-5 belting of the Yankees at Fenway.

When their tally reached a major-league record 41-9, the pennant race essentially was over. But the Fenway turn-stiles kept spinning as attendance more than doubled to over 1.4 million. One of the attendees, an Albany construction engineer named Joseph A. Boucher, found himself sitting in what became the most famous seat in the park on June 9 when Williams cracked a 450-foot homer that drilled a bulls-eye through his straw hat. “How far away must one sit to be safe in this park?” wondered Boucher, who was sitting in the 33rd row of the right-field bleachers, where the ball’s landing place later was memorialized by a red seat.

Williams hit 38 homers that season, not counting his two in the All-Star Game at Fenway. But the most important and least expected was his unorthodox round-tripper at Cleveland on Friday the 13

th

of September, the day the Sox won the pennant. Williams had been frustrated yet challenged by Cleveland manager Lou Boudreau’s “Williams Shift” that stationed everyone but the left fielder to the right of second base. “I’ve been planning for weeks to beat the crazy shift that Cleveland used against me,” he said. So Williams knocked the ball deep to left and legged it out for the only inside-the-park homer of his career and the only run of the game.

IN RIGHT FIELD, A SEAT OF POWER

BY DAN SHAUGHNESSY

It sits in a sea of green, a single red chairback in the outer limits of Fenway Park’s right-field bleachers. It is Seat 21 in Row 37 of Section 42. It is known simply as the red seat, and it marks the spot where Ted Williams hit the longest home run in Fenway history.

Like a fleck of red paint on a lush green canvas, the commemorative chair draws the eye. Someone is almost always sitting in it, even when just a few patrons are in the bleachers. New fans ask about the red seat, and citizens of Red Sox Nation are happy to relay the Fenway folklore.

Teddy Ballgame’s mighty clout was struck in the summer of 1946, on a windy, sun-splashed Sunday afternoon in the first inning of the second game of a doubleheader against the Tigers.

“Hell, I can tell you everything about that one,” Williams said from his Florida home in 1996—50 years later. “I hit it off Fred Hutchinson, who was a tough [righty] who changed speeds good. He threw me a changeup and I saw it coming. I picked it up fast and I just whaled into it.”

Indeed. The ball sailed over the head of right fielder Pat Mullin, and then carried beyond the visitors’ bullpen and kept on going. And then it crashed down onto the head of Joseph A. Boucher. More accurately, it landed on Boucher’s straw hat, puncturing the middle of the fashionable skimmer.

Boucher was an Albany, New York construction engineer who kept an apartment on Commonwealth Avenue when he worked in Park Square during the week. He loved baseball and the Red Sox. But sitting more than 30 rows behind the bullpen, he wasn’t expecting to catch any home-run balls.

Boucher spoke with the Globe’s Harold Kaese after the game and asked: “How far away must one sit to be safe in this park? I didn’t even get the ball. They say it bounced a dozen rows higher, but after it hit my head, I was no longer interested. I couldn’t see the ball. Nobody could. The sun was right in our eyes. All we could do was duck. I’m glad I didn’t stand up.”

Boucher went to the first aid room briefly, where he was treated by a doctor. He returned to watch the Sox complete their sweep of the Tigers.

The next day’s

Globe

featured a Page One photo of Boucher holding his hat, his finger stuck through the hole. The caption read, “BULLSEYE!”

Newspaper accounts claimed Williams’s homer traveled 450 feet, but the Red Sox measured the distance in the mid-1980s and arrived at an official distance of 502 feet.

“I got just the right trajectory,” said Williams. “Jeez, it just kept going. In distance, it was probably as long as I ever hit one.”

The bleachers were replaced with chairback seats in 1977 and ’78. In 1984, Sox owner Haywood Sullivan decided to commemorate Williams’s clout by putting a red chairback in the spot where Boucher sat on June 9, 1946.

If you find yourself sitting in Section 42, Row 37, Seat 21, don’t bother to bring a glove. There was only one man who could hit a ball that far, and he’s no longer with us.