Fenway Park (17 page)

Authors: John Powers

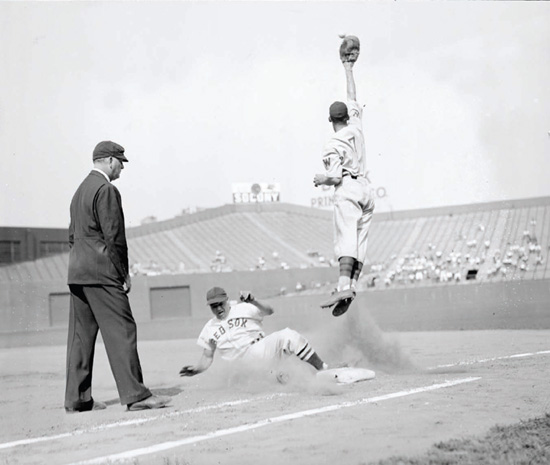

Jimmie Foxx of the Red Sox slid safely back into first base ahead of the throw to Washington Senators first baseman Joe Kuhel.

ENTERING WILLIAMSBURG

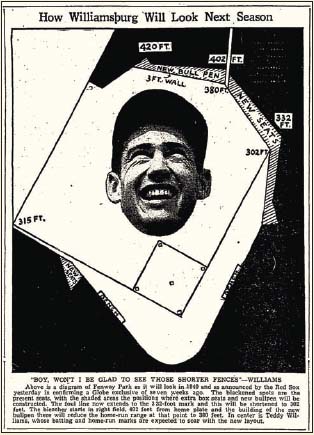

On September 24, 1939, the Red Sox announced that the home and visiting bullpens would be moved from foul ground into right and right-center field at Fenway in time for the 1940 season. The common expectation was that Ted Williams would propel home run after home run over the shortened fence. As the

Globe

put it, Williams’s “batting and home-run marks are expected to soar with the new layout.”

“Everyone thought,” Williams recalled years later, “that I was supposed to break Ruth’s record.”

After all, Williams was coming off a prodigious rookie season in which he had hit .327 with 31 home runs and a league-leading 145 RBI. There was little doubt that the reason for the ballpark reconfiguration ordered by Sox owner Tom Yawkey was to allow the Splendid Splinter, a pull hitter, to boost his number of round-trippers. The new warm-up pens were quickly dubbed “Williamsburg.”

The bullpens were constructed at the base of the existing bleachers, taking more than 20 feet off the home-run distance for the start of the 1940 season. The modification also led to the construction of extra seating at the bottom of the right-field grandstand. The rounded portion of the right-field wall—often called the belly—was another offshoot of the changeover.

In announcing the change, Sox GM Eddie Collins estimated that 600 to 700 box and grandstand seats would be added and provide sorely needed revenue for the team. Fenway’s home-run distance to the right-field foul pole shrunk from 325 feet to 302, while the right-field distance dropped from 402 to 380. As the Globe’s Harold Kaese wrote in a story in 1952, “Some optimistic experts predicted [Williams] would hit 75 home runs, or at least break Babe Ruth’s record of 60 with the park changed.” However, Kaese contrasted Williamsburg’s 380-foot distance in straightaway right field to the bullpens that had been constructed in the late 1940s in Pittsburgh, the so-called “Greenberg Gardens”—which required only a 335-foot poke from Pirates slugger Hank Greenberg. “Williamsburg,” Kaese concluded, “is no joke, but Greenberg Gardens . . . is a big laugh for a slugger.” Even with the new configuration, Fenway remained the longest right-center field fence to reach in the American League.

Kaese’s analysis in 1952 led him to pronounce that Williams had gained a total of 48 home runs over nine seasons (1940-42; 1946-51), or just over five a year from the reduced distances. Indeed, in 1940, the first season of the change, Williams actually hit fewer homers overall (23, down from 31) and fewer to right field than he had in his rookie season of 1939 (seven in 1939; five in 1940—four of which landed in the pens, one of which reached the bleachers beyond). Perhaps, Kaese wondered, Williams had pressed because of the expectations.

If nothing else, Williams made shrewd adjustments over his career. Kaese noted that in his first five seasons, Williams had not hit a single home run over the left-field wall, but in his succeeding five seasons, he hit 15. Kaese noted that the uptick coincided with the introduction by Lou Boudreau, the Cleveland Indians’ player-manager, of the Williams Shift, a realignment that left only one fielder to the left of the pitcher’s mound.

Twelve years later, Williams recalled the inflated expectations for 1940. “I didn’t hit the home runs that I had my first year,” he said. “I got a lot of catcalls and criticism. That just irked me enough, so I got a little sour on everything and everybody.”

That would not be the last time that Williams soured on the fans or the press in his brilliant, tempestuous 19-year career.

HERE’S TO YOU, MISS ROBINSON

Ted Williams called her “Sunshine.” Joe Cronin trusted her to babysit his sons. And Nomar Garciaparra never forgot to send her flowers.

For more than 60 years, Helen Robinson was the no-nonsense Red Sox switchboard operator who controlled access to the team’s decision makers, guarded its most explosive secrets, and ultimately created a legacy of loyalty and longevity.

“Helen Robinson was a legend, really,” said Red Sox GM Dan Duquette after Robinson, of Milton, Massachusetts, died of a heart attack in 2001 at age 85.

Robinson had witnessed it all with a telephone in her hand, all the sadness and glory that was Red Sox history for 60 years. She fielded condolence calls after the deaths of Thomas and Jean Yawkey, Tony Conigliaro, Joe Cronin, and one Sox great after another. And she endured the profanity-laced protests from fans after the most devastating losses on the field.

Robinson’s greatest admiration was for Tom Yawkey. “He wasn’t just a boss,” she said, “he was also a friend.” Although the switchboard went crazy whenever the Sox made a trade or were in a pennant race, Robinson remembered July 9, 1976, as her busiest day. That was the day the Red Sox announced Yawkey’s death.

“She has lived through some of the greatest and most trying moments in Red Sox history,” then-CEO John Harrington said at a ceremony marking Robinson’s 60

th

year on the job—one month to the day before she died, “and she will forever be entwined with Red Sox lore.”

A seamstress, Robinson knitted sweaters for Sox players who went off to World War II and Korea. Decades later, she helped sew tiny American flags on the backs of uniforms after the 9/11 terrorist attacks.

Robinson was working for New England Telephone in 1941 when she learned of an opening with the Red Sox. She was interviewed by Hall of Famer Eddie Collins, then the general manager, and landed the operator’s job.

“I was the only non-uniformed personnel he ever hired,” she proudly told people.

Those were the days of the telephone circuit board, when the operator needed to monitor the line to know when both parties were connected and disconnected on a call. Thus, she knew more about the inner workings of the Sox than almost anyone, but she never publicly whispered a word of it.

Nor did she betray the secrets she gathered by handling personal calls for players from Williams’s early years to Garciaparra’s heyday. And though the proliferation of cell phones curbed her contact with contemporary players, it was taken as much more than a minor observation when she first met Manny Ramirez and declared him “a fine young man.”

Robinson never married (“The Red Sox were her life,” Duquette said), and she counted Ted Williams among her closest friends. When they were young and single in the early 1940s, Robinson and Barbara Tyler, Collins’s secretary, often socialized with Williams, Johnny Pesky, and Charlie Wagner.

“She loved Ted,” Pesky said. “Ted always has called her ‘Sunshine.’”

When Elizabeth Dooley, generally considered the greatest Sox fan, died in 2000, Robinson was on the phone trying to contact Williams. “I knew Ted would want to know,” she said.

At her switchboard on the third floor at 4 Yawkey Way, Robinson worked from 9 a.m. until well after a home game ended, day or night. She left precisely at 5 p.m. when the team was on the road. And during weekend homestands, she arrived promptly on Saturdays and after church on Sundays.

In 60-plus years, Robinson was rarely absent. She kept working more than 20 years after she beat cancer in the 1970s. And she made no secret that she intended to work until she no longer was able.

“She went out doing what she wanted to do,” Manager Joe Kerrigan said when she died. “She worked till the last day. . . . I hope she gets her due. I hope people realize what she meant to the Red Sox.”

Although New York ran away with the pennant and the World Series, and the Sox ended up fifth, they still won more games (80) than they had since 1917 and their bankroller finally had a glimpse of a payoff. Boston would win a pennant “if it takes 1,000 years,” Yawkey vowed before the 1938 season, but his checkbook had a limit. “I’m through playing Santa Claus,” he declared when four players still were holding out on the eve of spring training.

As long as Yawkey had “The Beast,” he had a potent holiday punch, particularly at Fenway, where Foxx’s right-handed bat had the power of a cudgel. He had a monster campaign on the premises on the way to winning the league’s most valuable player award, hitting .405 at home with 35 homers, 104 RBI, and an .887 slugging percentage. His loudest thunderclap came at the end of an August 23 doubleheader against Cleveland, when Foxx crashed a grand slam with two out in the bottom of the ninth to give his team a 14-12 triumph and a sweep after they’d trailed, 6-0.