Fenway Park (19 page)

Authors: John Powers

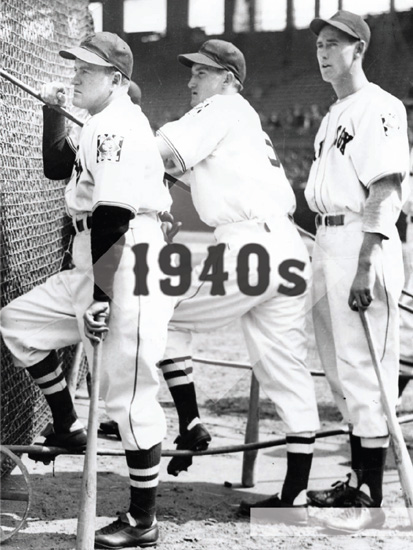

(left to right) Manager Joe Cronin, third baseman Jim Tabor, and left fielder Ted Williams at the Fenway Park batting cage.

T

he 1940s were tumultuous times. With the United States pulled into a world war on two fronts, baseball was greatly affected, even though the games went on. Because of wartime enlistments, the Red Sox only had their full complement of players early and late in the decade, and they ended the 1940s with one pennant, a seven-game loss in the World Series, and four runner-up finishes in the American League—including one that resulted from a one-game playoff loss. (The 1970s would produce exactly the same totals, although the American League had been split into two divisions by then.) In a decade that brought victory gardens, rationing, and the GI Bill, Fenway Park also became an important meeting place. It hosted military, civic, and religious gatherings, and it became the “neutral” setting for New England’s biggest college football rivalry of the era, Boston College vs. Holy Cross. Since politics has always been a wildly popular spectator sport in the land of the Kennedys, James Michael Curley, and

The Last Hurrah

, it is fitting that four-term President Franklin Delano Roosevelt gave the final campaign speech of his life from a platform at Fenway on the weekend before the 1944 election. Among 10-year epochs during their tenure in Fenway Park, the Red Sox seem to have developed a strong pattern of one good decade followed by two bad decades. They were at their most successful with four world titles in the 1910s, and then suffered through two mostly disastrous decades before returning to form as contenders through most of the 1940s. As the remaining chapters of this book will testify, it was a rinse-and-repeat cycle that kept going to the dawn of the 2000s.

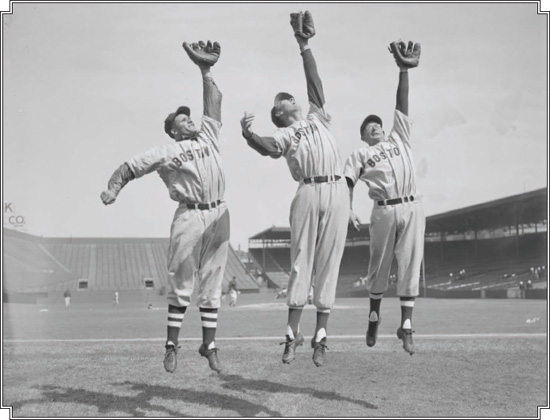

(left to right) Star players Bobby Doerr, Ted Williams, and Dominic DiMaggio obliged the cameraman by posing for this 1940 image.

A

s the Thirties ended, the Red Sox franchise had made the transition from a losing proposition to a winning proposition, even though the Yankees still were a mile ahead of Boston in the standings. The lineup, too, was in flux with Jimmie Foxx, Joe Cronin, and Doc Cramer nearing the end of their careers, and Ted Williams, Dom DiMaggio, and Bobby Doerr at the beginning of theirs.

Whether Williams, his teammates, or the fans liked it, he clearly was the future of the franchise. After the front office redesigned the park to suit him, the Kid was feeling the pressure in 1940, particularly since the homers were slow in coming. Even though the Sox were in first place (thanks to a 17-6 start and a torpid spring in the Bronx) and Williams was hitting well over .300, he felt unappreciated and was vocal about it.

What especially irked Williams was his $12,500 salary, given what he felt was expected of him. “Here I am hitting .340 and everybody’s all over me,” he complained in early June. “I shoulda been a fireman.” When Boston next played in Chicago, White Sox manager Jimmy Dykes, a notorious bench jockey, outfitted his players in papiermâché helmets, cranked up a siren, and had them howl, “Fireman, save my child!”

Once the Sox lost seven games in a row on the road in June—four of them to the fifth-place St. Louis Browns—and then dropped another eight straight in July, all of the engine-and-ladder companies in the Hub couldn’t save them and they ended up in fourth place. Yet Williams, for all his angst, had an exceptional season, hitting .344, clouting 23 homers, and knocking in 113 runs. He even pitched the final two innings in a mop-up role against Detroit in late August. Williams held the Tigers to one run on three hits and struck out Rudy York on three pitches, though the Sox lost, 12-1.

That season was prelude to an achievement that has been unmatched since, as Williams hit .406 in 1941, even while opposing hurlers were pitching around him, walking him 147 times in 143 games. The biggest challenge for the club at first was to find him, as Williams absented himself from spring training, phoning in once to assure the front office that he hadn’t been abducted. “Theodore says he has been so busy shooting wolves in a country so wild that no paths led from there to civilization,” Mel Webb wrote in the

Globe

.

When Williams finally turned up, he was both relaxed and reflective, eager to put the tumult and torment of the previous season behind him. He even “shook hands all around” with newspaper reporters, the

Globe

reported on March 10. “They said I was a heel and I’ll admit I had a lousy attitude,” he later conceded in June. “But I don’t think I deserved all they wrote about me, even though I have to admit the start of it all probably was my fault.”

Nobody could find a flaw in his performance, as Williams went on a 23-game hitting streak during which his average soared to .436. “The Kid has grown up,” the

Globe

declared.

When he hit the game-winning, three-run homer with two out in the ninth inning in Detroit to win the All-Star Game for the American League, there was no doubt about who was baseball’s most electrifying player. By then the Sox had fallen out of contention after being swept at New York. The only two story lines keeping Boston fans intrigued were Ted Williams’s quest to hit .400 (something no one had done for a full season since 1930) and Lefty Grove’s push to reach 300 career wins.

It had been 16 years since his first victory and Grove was at the end of his career at age 41. When he took the mound against the Indians on Ladies Day in Fenway, he hadn’t won a game in more than three weeks. The thermometer read 90 degrees and Grove fell four runs behind. “The toughest game I ever sweated through,” he said. But Foxx’s two-run triple and Jim Tabor’s second homer gave the Sox a 10-6 triumph and Grove, who never won another game, his 300

th

career victory. Grove was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1947.

An American Legion memorial Mass on May 20, 1940.

FOOTBALL, FATE, AND THE COCOANUT GROVE

In 1896, Boston College and Holy Cross played the first game in what was to become one of the longest-running rivalries in college football. In 1916, the schools squared off at Fenway Park for the first time, and in 1920, BC capped an 8-0 season with a 14-0 victory over Holy Cross before 40,000 fans at Braves Field.

BC hired Frank Leahy as coach in 1939, and he turned the Eagles into a national power that won 20 of 22 games over the next two years, including an undefeated season in 1940 and two straight victories in the Sugar Bowl in 1940 and 1941.

The Eagles were routinely dominating their rivals from Worcester, and entering the 1942 matchup at Fenway Park, undefeated BC had routed its eight previous opponents that season by a combined 249-19 and was nearly assured of a berth in the Sugar Bowl. Holy Cross was 4-4-1, and the Crusaders were expected to provide little resistance. BC had already scheduled a victory party at the swanky Cocoanut Grove nightclub in Boston.

A crowd of 41,350 packed Fenway Park on November 28, and, led by halfback Johnny Bezemes, who scored three touchdowns and passed for another one, Holy Cross proceeded to rout the vaunted Eagles, 55-12. Seeing its expected spot in the Sugar Bowl vanish, BC canceled its victory party. That night, a deadly fire swept through the glitzy Cocoanut Grove nightclub, killing nearly 500 people in the worst nightclub fire in U.S. history. A BC victory surely would have resulted in the deaths of some of its football players, as a large table had been reserved for the team in the club’s main dining room.

William Commane, a fullback on the 1942 BC squad, had planned to be at the Cocoanut Grove that night, but like his teammates, he switched plans after their loss and went to the Statler Hotel. “The next day, I was listening to the radio at home with my family,” Commane recalled. “They read out the names all day; it was a terrible tragedy. The football game didn’t mean much after that.”

The teams’ annual clash in 1956, a 7-0 Holy Cross victory, would be their final contest at Fenway Park, as the Red Sox banned football from the ballpark for several years. Shortly thereafter, the schools took different athletic paths, with Holy Cross deciding to de-emphasize the sport. In 1986, after losing 17 of the previous 20 games to BC, Holy Cross terminated the series.

LIB DOOLEY: ULTIMATE FAN

Elizabeth “Lib” Dooley got her first season ticket during World War II and didn’t miss a Red Sox home game for the next half-century, attending more than 4,000 consecutive ballgames at Fenway. She had a direct link to the franchise’s beginnings in 1901 through her father, and she sat in the first row behind the Red Sox on-deck circle in Box 36-A. Mickey Mantle would stick out his tongue at her when he homered for the Yankees, and she was Ted Williams’s favorite fan.

“Forever, she’s the greatest Red Sox fan there’ll ever be,” said Williams in 1996.

Dooley, who retired after 39 years as a physical education teacher in Boston, said that she attempted to guide her students in the right direction by telling them, “I don’t drink, I don’t smoke; I go to ballgames.”

Dooley fell in love with the sport in an era when she was one of the comparatively few female baseball fans. She grew up hearing the men in her family share stories about the game and looked forward to days when she could accompany her father to the ballpark.

Dooley decided to buy her own season pass in 1944 and “make baseball my hobby.” One of her sisters had taken up bridge, but Dooley didn’t have the stomach for that: “I despise bridge and I hate gossip. I wanted something where I could go by myself without anyone ruining it by saying, ‘I can’t do it this week.’ It gets you out in the fresh air and keeps you from talking about your neighbors.”

Dooley’s father, John Stephen Dooley, helped the upstart American League ballclub get a home at the Huntington Avenue Grounds in 1901. He was also the founder and president of a boosters group known as the Winter League, a forerunner to today’s BoSox Club. According to family lore, Dooley attended every Boston baseball opener from 1894 until his death at the age of 97 in 1970.

Lib Dooley went on to become a member of the board of directors of the BoSox Club, the team’s official booster club. In 1956, she moved to Kenmore Square so she could walk to Fenway. “It’s seven minutes to the ballpark, a little more now as I get older and the crowds get bigger,” she said in 1995.

Williams lived nearby, and during his playing days he would visit her apartment on his way to the park, stopping by for “her words of wisdom for the day.”

“Theodore trusts me,” Dooley explained, “because he knew I was a schoolteacher and I would talk to him straight.” Dooley recalled telling Williams that he’d never know who his real friends were until he left the game.

For his part, Williams called her “Goddammit Red,” as in: “Goddammit Red, how do you know that?”—even as her red hair became tinged with silver.

Along with Williams, her favorite players were Bobby Doerr, Dom DiMaggio, and Johnny Pesky. She called them “my four baseball brothers.”

“She was just a perfect lady,” said DiMaggio in June 2000, after Dooley died at 87. “I remember so well when she presented us with our American League championship rings after we won in 1946. She was so thrilled. The Red Sox were practically her whole life.”

Dooley took at least one road trip with the team every year, and she claimed she’d seen five no-hitters. Despite her prime location, she fielded only one foul ball—a pop-up off the bat of Sox outfielder Carroll Hardy in the early 1960s. She broke two fingers in the effort and never attempted to catch another.

Jim Rice was a favorite in the 1970s and 1980s, and later on, she took to Nomar Garciaparra. “Nomar would give her a wink when he came into the on-deck circle,” said David Leary, her grandnephew.

Her strongest negative feelings were reserved for the team in pinstripes.

“I despised the Yankees,” she said, “because they gave us so much trouble. They always beat us, always.” Joe DiMaggio, Phil Rizzuto, and Mantle “were the only three Yankees who I tolerated, because of their great talent.”

“The fans are really baseball, not the players,” Dooley said when a strike marred the 1994 and 1995 seasons. “You can always get someone to play ball—it doesn’t have to be someone who gets $4 million to work two hours a day.” A moment later, she added with a grin, “I wonder if I’m going to need a bodyguard to get back into that park.”

Dooley once explained her position thusly: “I do not consider myself a fan. I am a friend of the Red Sox.” An anecdote from her nephew, Owen Boyd, backed up that statement.

Boyd was at a game with Dooley when she directed him to dial a number for her on his cell phone. To his astonishment, “Happy birthday, Theodore” were the next words out of her mouth.

“You know Ted Williams?” Boyd asked in amazement.

“More importantly,” she replied, “Ted Williams knows me.”