Fenway Park (45 page)

Authors: John Powers

McNamara did get the blame in 1988 when a $6 million palimony suit filed against Wade Boggs by companion Margo Adams made national news and created clubhouse dissension. With the team barely above .500 at the All-Star break, owner Jean Yawkey concluded that McNamara had to go and fired him against the wishes of both Sullivan and Gorman. “We want to try and turn this thing around,” said Gorman. “We’re not saying that John McNamara didn’t do a good job, but the manager is always the scapegoat—fairly or unfairly.”

Stepping in with just a few hours of notice was Third-Base Coach Joe Morgan, a Walpole, Massachusetts, native who’d managed the PawSox for nine years and was the first local resident to manage the Boston Red Sox since Charlestown-born Shano Collins in 1932. “Communication is important,” he acknowledged during his first day on the job. “You have to talk to players. But if they get out of line, you have to step on ’em.”

The first to feel Morgan’s tread was the captain. When Rice objected loudly after being pulled for pinch hitter Spike Owen, he and Morgan shouted and scuffled in the dugout and Rice was suspended for three games. “I’m the manager of this nine,” Morgan declared.

By then the Sox already were up and away on their best run since 1948, a 12-game winning streak that included a six-run comeback over the Royals. “It’s unbelievable, really,” marveled Stanley. “I’m shocked. We’re winning games we were losing before.”

It was “Morgan Magic,” the press declared, a spell conjured by a plainspoken citizen who channeled the catchphrase, “Six, two and even,” drove a snowplow along the Massachusetts Turnpike during the off-season, and seemed unfazed by a position that had driven some of his predecessors to drink. “There is no pressure, gentlemen,” Morgan declared as his nine ascended the standings, winning 19 of 20. “I had more pressure trying to hit in the big leagues than I do managing.”

By Labor Day, the Sox were in first place for good and despite dropping six of their final seven games—including 11-1, 15-9, and 1-0 home losses to Toronto—Boston still won the division by a game over Detroit and earned a playoff date with Oakland. Boston had dismissed the Athletics en route to the 1975 World Series, but this edition of the A’s proved to be decidedly more stubborn.

In the opener at Fenway, Hurst pitched well enough to have won most playoff outings. But Oakland pitcher Rick Honeycutt starved the hosts until old friend Dennis Eckersley entered in the eighth to finish off his former mates, whiffing Boggs on three pitches with two on and two out in the ninth. “We’ve got to come back tomorrow with the hammers of hell,” declared Morgan. That meant Clemens firing ingots from the mound. But the visitors rallied from two runs down on Jose Canseco’s two-run blast in the seventh, nicked Lee Smith for the winner with two out and two strikes in the ninth, and brought in Eckersley again to tie the Sox in knots.

THE MANIACAL ONE

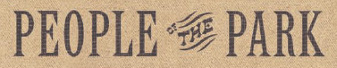

“Sometimes the truth hurts,” said Chuck Waseleski with a chuckle when asked about his nickname. “It’s true. I can’t refute it.”

Waseleski, known as “The Maniacal One” for his devotion to baseball record-keeping, came along before computers and fantasy baseball exploded onto the sports scene, before situational statistics, before obscure but telling numbers became necessary fodder for sports talk shows and play-by-play announcers looking to fill air-time. He provided these statistical insights to Peter Gammons, who began to include them in his nationally recognized Sunday baseball column for the

Globe

.

“You hear that so-and-so is a good two-strike hitter,” he said to the

Globe

’s Dan Shaughnessy in 1987. “I hate that. I want to know how good. Be specific.”

Maniacal Chuck was born and raised in the village of Millers Falls, Massachusetts, and he went to Turners Falls Regional High, where he was class valedictorian in 1972. Like a lot of New Englanders, he was a casual Red Sox fan until the 1967 Impossible Dream season. “That hooked me for good,” he said.

In 1982, he began corresponding with Bill James, author of the annual Baseball Abstract. “It was then that I realized there was some demand for this material,” Waseleski recalled. “People would ask, ‘Is Jim Rice a clutch hitter?’”

Waseleski had the information. He could tell you that “Wade Boggs is hitting .488 (21 for 43) on 1-0 counts this year.” Or, “Ed Romero hit the ball off the left-field wall twice in 1986.” Waseleski has watched and charted every Boston game—every single pitch—since 1983, which happens to be the year Boggs won his first batting title.

“Oh, yeah,” Boggs told Tampa Tribune columnist Martin Fennelly just before he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 2005. “He was the guy that would tell everyone how many times I popped up to the infield and kept crazy stats on me, like how many times I swung and missed.”

Before long, players and their agents were using such numbers to their advantage in salary arbitration cases. Waseleski compiled negotiation files for 30 players after the 1985 season, and for 70 players after the 1986 season.

In October 2004, when the Red Sox won their first World Series since 1918, many people wept. Waseleski typed into his Dell.

“I can tell you exactly what I wrote when we won it. I have it right here. I wrote that it was a 1-0 count, a fastball, and a ground ball back to the pitcher. It was Keith Foulke’s 14

th

pitch,” he told Fennelly.

Maniacal as always.

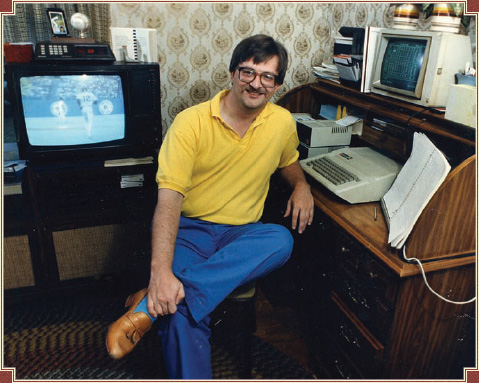

The Wave passed by Roger Clemens and Oil Can Boyd, who were focused on other things in the dugout during a 1986 regular-season game.

Morgan shook up his lineup as the series moved to the Bay Area and Boston grabbed a 5-0 lead in the second inning of Game 3. But Oakland’s bashers quickly pounded Mike Boddicker for six runs and went on to a 10-6 decision that left the visitors on the brink. “We got a game left,” said Boddicker, who’d arrived from Baltimore at the end of July. “We got a bullet left. It hasn’t been done in baseball, but records are broken all the time.”

Not this time. In the finale, Oakland’s Dave Stewart scattered four runs across six innings and Eckersley came in to complete the sweep by closing out his fourth game. “All we have is some [hats and T-shirts] that say ‘AL East champs,’” Boston’s Todd Benzinger commented once the drubbing was done. “We never really got to enjoy it.”

Joy remained scarce in 1989 as Boston finished third, a half-dozen games off the pace and with no playoff hopes. The dissolution began in late May, when the club lost six of eight games at Fenway and drifted downward from first place. By far the worst of the defeats—in fact, the biggest collapse in franchise history—was a 13-11 loss to Toronto in which the Sox blew the 10-0 lead they had mounted in six innings. “What a loss,” moaned Morgan, after Ernie Whitt had crushed a grand slam off closer Lee Smith in the ninth and Junior Felix had clouted a two-run shot off Dennis Lamp in the 12

th

inning of the four-hour-and-36-minute fiasco. “This is the worst defeat of my managerial career in any league or city, hands down.”

When Boston had climbed back to within one-and-a-half games of the lead in mid-August, the Blue Jays returned to put them out of the race with a sweep. “Is it the president?” someone asked Morgan when the phone rang after the season finale with Milwaukee. “I doubt it,” the skipper said.

The video scoreboard in center field was removed on October 16, 1987. It was replaced by a version with Diamond Vision technology.