Fenway Park (43 page)

Authors: John Powers

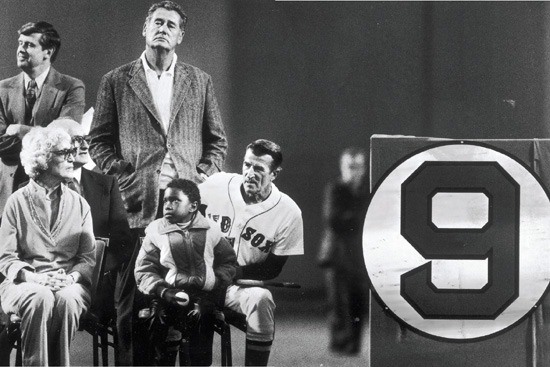

Ted Williams stood, typically forgoing a tie, during the ceremony in which his No. 9 was retired, along with Joe Cronin’s No. 4, on May 28, 1984. Team owner Jean Yawkey and former teammate Johnny Pesky joined the festivities.

YAZ SHOWS HE’S HUMAN

Carl Yastrzemski always wanted the other team to think that he was a machine. He wanted the pitcher to stare in and see a hitting robot staring back from the plate.

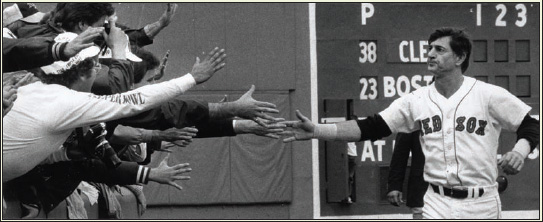

But on October 1, 1983, in his final game after 23 years of faithful service, Yaz broke down in full public view, before a sellout crowd at Fenway Park.

“I thought I had it under control,” Yastrzemski said. “But then, when I started to hear the fans . . . that’s why I put my head down when I got to first base.”

For most of his final season, Yaz hadn’t wanted any fuss. He just wanted to be what he always had been—the ballplayer, the worker. On this day, he endured the speakers and their kind words and the bows, until Yastrzemski himself was speaking, asking for a moment of silence for his mother and for former owner Tom Yawkey.

“New England, I love you,” Yaz finally said, and then he was running around the perimeter of the field, touching as many hands as he could.

“I wanted to show my emotions,” he said. “For 23 years, I always blocked everything out. I wanted to show these people that deep down, I was emotional for all that time.”

When Yaz retired, he had played in more games (3,308) than anyone in baseball history, all of them for the Red Sox.

“I’ve always had tremendous happiness coming to this ballpark,” said Yaz in a 1989 interview. “Never in my life did I think I’d make the Hall of Fame and have my number retired. I worked, and just working so hard overshadowed everything. I never enjoyed it after a game in which I did well. I was always thinking about tomorrow. I just never dwelled upon the success.”

“I came to love Fenway. It was a place that rejuvenated me after a road trip; the fans right on top of you, the nutty angles. And the Wall. That was my baby, the left-field wall, the Green Monster.”

—Carl Yastrzemski

Clemens went on to submit a 9-4 record, and with the outfield of Rice, Tony Armas, and Dwight Evans combining for 103 homers and 349 RBI, Boston managed to post 86 victories and climb to fourth place.

The club’s transition complete, Houk retired at the end of the season and was succeeded by John McNamara, who’d been managing the Angels. “Am I too late to apply for the job?” Don Zimmer jokingly asked Sullivan over the phone after the announcement was made. Even before he’d checked into his hotel room upon arrival, McNamara discovered what Zimmer had learned—that everyone in New England was a would-be manager. “Is Rice going to hit fourth?” the Sheraton-Boston bellman inquired.

Rice batted third until August, but his 1985 season was cut short by a knee injury. Armas missed nearly two months with a torn calf muscle, and Clemens, dogged by a shoulder injury that required late-summer surgery, had only 15 starts as Boston finished fifth, more than 18 games behind the Blue Jays. “It’s certainly not the kind of record I had in mind when I came here,” McNamara conceded after his club was swept at home by the Brewers on the final weekend to end with a .500 record. “To me, this has been a very disappointing season.”

In 1986, the disappointment was limited to two October nights in Queens, but it was painfully profound. The regular season, highlighted by Clemens’s record 20-strikeout performance against the Mariners in April, proved surprisingly easy as the Sox held first place from May 16 until the end, won 95 games and claimed the division by five-and-a-half games despite losing the final four to the Yankees at home. “The usual rallying cry around here is, ‘Wait until next year,’” remarked McNamara as his men prepared to take on the Angels in the league championship series. “Well, next year starts Tuesday night. We’re prepared.”

Boston hadn’t played a postseason game since the one-game divisional playoff in 1978 with the Yankees, and the ALCS opener at Fenway was over almost as soon as it began. The visitors rocked Clemens for four runs in the second inning. “We’ll be all right,” Clemens insisted after California counterpart Mike Witt took a no-hitter into the sixth inning and wrung out the Sox by an 8-1 count.

THE LEROUX COUP

In the annals of bizarre incidents at Fenway Park, probably none can top the night of June 6, 1983. The Red Sox had announced plans to honor former player Tony Conigliaro, who had been in a coma for months following a stroke. Many of his teammates from the revered Impossible Dream team of 1967 were gathered, along with a large media contingent.

Co-owner Buddy LeRoux interrupted the proceedings to announce that enough of the team’s partners had voted in his favor to give him control of the Red Sox over co-owners Haywood Sullivan and Jean Yawkey, with whom he had been feuding for years. A half hour later, Sullivan and John Harrington, representing the Yawkey Foundation, held a rebuttal news conference to announce that the team’s chain of command was intact, and that LeRoux’s announcement was “illegal, invalid and, above all, not effective.”

“Le Coup LeRoux,” as it was dubbed, reduced the celebration of the 1967 team and the stricken Conigliaro to an afterthought.

In the next day’s paper,

Globe

columnist Michael Madden wrote, “Buddy LeRoux and his bottom-line men did not have the patience, the class, the sensitivity, the good taste or even the most basic respect to wait another day.” Madden called it “a sideshow, a shoddy, slippery coup by banana-republic generals. . . . What was to have been the Night of the Impossible Dream was transformed meanly into the Day of the Shameful Scene.”

Former player George Thomas watched the competing news conferences, both held directly under a color portrait of the late, longtime owner of the Sox, Tom Yawkey.

“If he could see this now,” said Thomas, “he’d be spinning in his grave.”

Ironically, LeRoux had developed a strong bond with the Yawkeys as the team’s trainer in the 1960s. He went on to build a real estate empire, and in 1977, with Sullivan as his partner, LeRoux led a group that sought control of the Red Sox after Tom Yawkey’s death. When some questions arose about financing, Jean Yawkey joined the consortium and the sale was approved by Major League Baseball.

LeRoux took over the business end of the Sox operations, guiding the construction of luxury boxes at Fenway and signing lucrative TV and radio contracts. Before long, however, the ownership group became divided, leading to the stunning events of “Tony C Night.”

The outcry over LeRoux’s takeover bid was immediate and harsh. He was taken to court by Yawkey and Sullivan and eventually lost the battle for control of the team. Once he realized that he would never be able to buy the others out, LeRoux sold his shares to Yawkey in 1987.

Boston indeed bounced back the next afternoon. The sun-blinded Angels ran into outs, watched balls skip over and away from them, and made three errors in the seventh inning—when the hosts scored three runs on one hit. But the Sox dropped the next two in Anaheim, including a killer 11

th

-inning loss in Game 4 after they’d blown a 3-0 lead in the ninth with Clemens on the mound. It seemed that the season would end on the Left Coast, especially when the Angels took a three-run lead into the ninth inning of Game 5. Don Baylor cranked a two-run homer to draw the Sox to within 5-4, but pretty soon the visitors were down to their final strike, and the home team was preparing to rush the diamond in triumph. “I looked across the field and I could see everyone in the Angels dugout getting ready to celebrate,” said Boston’s Dave Stapleton. “Gene Mauch. Everyone. They had those little smiles that you get before you start hugging everyone.”

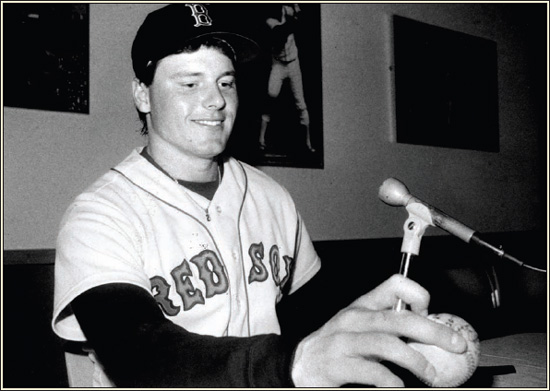

THE ROCKET’S AWESOME COMING-OUT PARTY

As the 1986 Red Sox season opened, Roger Clemens was a 23-year-old question mark coming off shoulder surgery that curtailed his 1985 season. But he turned the question mark into an exclamation point on a weeknight in late April when the Red Sox game was playing a distant second fiddle to a Celtics-Atlanta Hawks playoff game that featured Larry Bird across town at the old Boston Garden.

Only 13,414 fans were on hand at Fenway Park on April 29 to see “Rocket Roger” do something that no pitcher in 111 years of major-league history had managed to do before: strike out 20 batters in a nine-inning game.

The Mariner lineup included a couple of guys who would later factor into Boston’s amazing run to the 1986 World Series: Spike Owen and Dave Henderson. Owen had also been Clemens’s teammate at the University of Texas. Clemens came into the game with a 3-0 record, which would eventually grow to 14-0 en route to a 24-4/MVP/Cy Young Award season. Clemens struck out the side (all swinging) in the first inning. He fanned two more in the second and one in the third. Although he went to three balls on five of the first nine batters, he ended up with zero walks to go along with his 20 strikeouts.

After giving up a single to Owen to start the fourth, Clemens struck out eight in a row, tying an American League record. But in the seventh inning, Seattle’s Gorman Thomas drove a 1-2 fastball into the center-field bleachers to give Seattle a 1-0 lead. Amazingly, Clemens was on his way to history, but was in danger of losing the game. Fortunately, Dwight Evans crushed a three-run homer in the bottom of the inning to put the Sox ahead, 3-1, the eventual final score.

Clemens had 18 strikeouts after eight. Owen struck out on a 1-2 fastball to open the ninth, and when umpire Vic Voltaggio rang up Phil Bradley on an 0-2 fastball for No. 20, Wade Boggs jogged to the mound from third base and shook Clemens’s hand. Ken Phelps grounded to shortstop for the final out on Clemens’s 138

th

pitch.

Clemens would go on to throw another 20-strikeout game (no walks again) in Detroit 10 years later, but this was the night that signaled Clemens’s ascendancy.

“In the clubhouse afterward,” General Manager Lou Gorman said, “even the veterans were awed.”

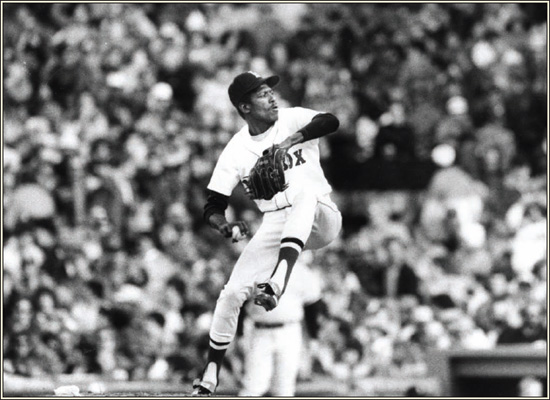

‘OIL CAN’ KEPT US GUESSING

In the 1980s, few people called him by his given name, Dennis. Years later, “Oil Can” Boyd told Dan Shaughnessy, “I’m blessed with this mystique. I got a nickname and I know how to pitch.”

The Can started 207 games in his 10-year MLB career. He started the third game of the 1986 World Series and was lined up to pitch Game 7 before rain and Red Sox Manager John McNamara changed history. The Can went 78-77 in the big leagues with a 4.04 ERA and pitched the division-clinching game for the Sox in 1986. But his favorite baseball memories come from his younger days in Meridian, Mississippi.

“That was the most fun, around when I was 12-15 years old,” he recalled. “Baseball was the epitome back then. I played a lot of baseball when I was little, so I have big reminiscences of baseball and that’s how I came to be the player I came to be.”

Boyd could throw a ton of innings and he always wanted the ball. Baseball was in his blood. His dad, Willie James Boyd, once faced Henry Aaron and Willie Mays at the ballpark in Meridian. Dennis Ray Boyd was nicknamed “Oil Can” because of his fondness for beer (the nickname gets a special citation from Susan Sarandon in

Bull Durham

), and he became one of the more delightful characters on the Boston sports scene after splashing down in 1982. Manager Ralph Houk—and later McNamara—didn’t know quite what to make of the Can, but they knew he wanted the ball every fifth day and that he could pitch.

There was plenty of controversy. The Can was hospitalized with a mysterious liver ailment in 1986, and then went into a rage and temporarily quit the Sox when he didn’t make the All-Star team. There were rumors of drugs, and he got into a jam with the police. The Sox subjected him to a psychological evaluation and went public with their concerns. When team-mate Wade Boggs announced he was a sex addict a few years later, Can said, “Now who needs the psychiatrist?”

In the end, blood clotting in his throwing shoulder took Boyd away from the game he loved. He pitched for the Expos and Rangers before retiring after the 1991 season.