Fenway Park (49 page)

Authors: John Powers

Again, the opponent was Cleveland, and this time the Sox sensed that they were in for a reversal of fortune. Martinez stifled the Indians and Vaughn whacked two homers and knocked in seven runs in an 11-3 slamdown at Jacobs Field. “This is just the start,” declared Dennis Eckersley after Boston had won its first postseason game since 1986. Everything was going the visitors’ way when Indians Manager Mike Hargrove and starting pitcher Dwight Gooden were ejected and the Sox took a 2-0 lead in the first inning of Game 2.

But the Indians battered Tim Wakefield to salvage a split, and when they cranked three homers off Bret Saberhagen and another off Eckersley in the ninth inning of the first Fenway game, the Sox suddenly found themselves on the brink of elimination. “Please, Jimy, please pitch Pedro,” Boston fans implored Sox Manager Jimy Williams as he walked toward the clubhouse.

Rather than use Martinez on three days’ rest, Williams opted for a fresh Pete Schourek, who’d been scooped up from Houston in August. “The bottom line is we’ve got to win two games,” said Saberhagen, “and Pedro can’t win them both.”

For seven innings of Game 4, Boston thought that it would even the series. Schourek was pitching a shutout and Garciaparra, who had a divisional series record 11 RBI, had put his team ahead with a leadoff homer in the fourth. When Tom “Flash” Gordon came in to wrap up things in the eighth, it seemed that the Sox would force a decisive fifth game with Martinez on the mound.

But Gordon, who’d strung together 43 saves in a row and hadn’t blown one since April, conceded a two-run double to David Justice that gave the visitors a 2-1 decision. If Red Sox third-base coach Wendell Kim hadn’t rashly waved home John Valentin for a damaging out in the sixth or if the autumnal wind hadn’t reduced Vaughn’s would-be tying homer to a Wall double in the eighth, Boston might have survived. “I’m pretty surprised it ended this way,” Valentin remarked as the Sox cleaned out their lockers. “I anticipated that we’d go far.” Instead the Indians earned a quixotic date with the Yankees. “There’s nothing to watch,” declared Garciaparra. “We won’t be there.”

THE LONG GOOD-BYE

In May 1999, the Red Sox were gearing up for their first hosting of baseball’s All-Star Game in 38 years. As far as the team was concerned, that summer’s All-Star festivities would also provide an opportunity to say a gracious good-bye to Fenway Park, then 87 years old.

“Fenway is a wonderful ballpark,” said John Harrington, chief executive officer of the Red Sox at the time. “But the sad truth is it’s economically and operationally obsolete. It just doesn’t allow us to compete like teams with modern ballparks do.”

What the Sox hoped to sell to fans, political leaders, and the public was a new Fenway Park built right next door to the old one, “with the intimate scale and feel of the old” but up to 30 percent larger with modern conveniences and revenue streams.

As head of the JRY Trust that controlled the team, Harrington wanted to replace the existing 33,871-seat park with a new facility for 45,000 fans. Plans called for it to be built on roughly 14 acres bordered by Boylston Street, Brookline Avenue, and Yawkey Way.

Residents of the Fenway neighborhood and ballpark preservationists demanded that the park not be razed, but renovated. Harrington said he had studied several renovation options and rejected all of them.

Said Dan Wilson, a leading member of a group called “Save Fenway Park” and a Boston lawyer: “The Red Sox will be throwing out their most important asset if they build a new ballpark.”

The Sox attempted to assuage that argument by offering plans to forever preserve parts of Fenway—a portion of the left-field wall, the 1912 brick entrance, and the entire infield—as a tourist attraction and open space.

After years of wrangling with city planners and park preservationists, the JRY Trust abandoned its new ballpark bid and put the team up for sale. Among the final five bidding groups in 2002, only the New England Sports Ventures group led by John Henry was committed to retaining the original ballpark. Interestingly, several of the options proposed by the Save Fenway Park contingent were ultimately implemented by Henry and his winning group, including the expansion of walkways and concession space inside the park, and the closing off of Yawkey Way to provide a game-day fan concourse.

Red Sox CEO John Harrington pointed out details of the proposed new Fenway Park to MLB commissioner Bud Selig (center) and Red Sox General Manager Dan Duquette (right) before the 1999 All-Star Game.

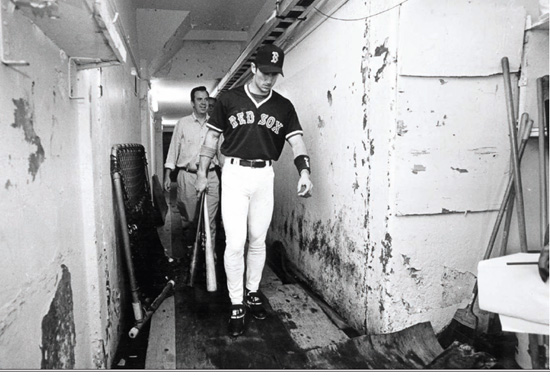

Nomar Garciaparra walked down the runway toward the Red Sox dugout with Red Sox Director of Communications Kevin Shea in 1998.

Boston was there in 1999, even after Vaughn decamped for Anaheim for $80 million over six years. Despite spending time on the disabled list with an uncooperative shoulder and squabbling with Duquette, Martinez won 23 games, including a one-hitter at New York in September. Though the Yankees, as usual, proved uncatchable, Boston did snare another wild-card spot for the playoffs and another meeting with the Indians.

After the Sox dropped the first two games of the divisional series in Cleveland—the second by an ugly 11-1 margin—they returned to Fenway facing extinction yet again. But they managed to stay alive with a pyrotechnic display in the seventh inning of Game 3, scoring six runs with two out on Valentin’s two-run, bases-loaded ground-rule double, rookie Brian Daubach’s three-run homer, and Lou Merloni’s two-on single, to secure a 9-3 triumph.

Few would have predicted the next day’s result, when the Sox literally put up telephone numbers in a 23-7 T-ball contest that drew them even. “Everything we threw up, they hit and where it came down, we weren’t standing,” observed Hargrove. No Boston team ever had punished as much horsehide in one October day. Three homers, two of them by Valentin, who knocked in seven runs. Twenty-four hits, including a dozen for extra bases. A 10-2 lead after three innings, 15-2 after four, 18-6 after five. “It’s a one-gamer now,” concluded Williams.

So the Sox headed back to The Jake for the finale with a most appropriate, yet least likely figure providing their deliverance. Martinez had lasted only four innings in the opener before straining his back trying to blow a fastball past strongman Jim Thome. “I didn’t know when Pedro could pitch again,” admitted Joe Kerrigan, the Sox pitching coach. But after the Indians had pummeled Saberhagen and Derek Lowe for eight runs in three innings, Martinez came out of the bullpen to hurl six scoreless innings and stake his compañeros to a 12-8 triumph that put them into the league championship series for the first time since 1990.

The club’s first postseason series victory since 1986 earned the Sox their first October date with the Yankees since the one-game 1978 playoff. “They better sweep us,” warned Valentin. “They better sweep us, baby.” By the time the Sox returned to Fenway, they were down two games after being edged, 4-3 and 3-2, in the Bronx, despite leading each night. They still had one defiant and glorious game left in them, though, and their 13-1 destruction of New York on Saturday afternoon delighted the full house, especially since it came at the expense of Clemens, who’d exchanged plumage for pinstripes in February.

A vendor offered soda (real New Englanders call it tonic) in July 1995.

Programs were hawked on Yawkey Way before the 1997 home opener.

The view from atop the Green Monster at sunset, with both the ballpark and Lansdowne Street packed.

A STAR AMONG STARS

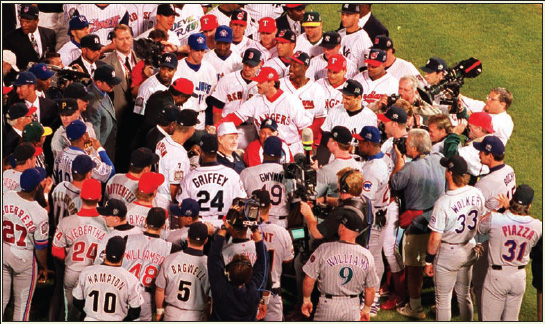

Baseball’s All-Star Game frequently fails to live up to its hype. When Fenway Park hosted its third All-Star Game in 1999, the result was a 4-1 American League victory that featured zero home runs. But there will never be another sight like that of Ted Williams, who threw out the ceremonial first pitch, being engulfed by other baseball greats, including Stan Musial, Willie Mays, Bob Feller, Hank Aaron, Bob Gibson, and Cal Ripken Jr., just to name a few.

The ovation was loud and long. “I thought the stadium was going down,” said Pedro Martinez afterward.

The moment made a lasting impression on Mark McGwire of the St. Louis Cardinals. “When you have a chance to meet one of the best hitters in the game,” said McGwire, “and you see tears running down his eyes because of the appreciation that the fans and all of us gave him, it becomes a very special time.”

Introduced as “the greatest hitter who ever lived,” Teddy Ballgame, 80, rode into Fenway on a golf cart. After a lap around the field, Williams was brought to the mound, where he was surrounded by both All-Star squads and 31 of the top 100 ballplayers in baseball history. It was without question the greatest assemblage of hardball talent ever gathered on any diamond. With a giant No. 9 stenciled into the outfield grass, and the ancient theater shaking on its foundation, Williams stood in front of the mound and delivered a strike to Carlton Fisk, the longtime Red Sox catcher and his soon-to-be fellow Hall of Famer.

The hero of the 1999 AL victory was Red Sox ace Pedro Martinez, who struck out five of the six batters to face him—Barry Larkin, Larry Walker, Sammy Sosa, McGwire, and Jeff Bagwell—and was voted the game’s MVP. But even Pedro took a backseat to Williams.

“I don’t think that there will be any other man that’s going to replace that one,” said Martinez.

“It was like something out of Field of Dreams,” said Cleveland’s Jim Thome.

Said a young woman in the stands, “Oh, my God. Ted Williams threw a pitch to Carlton Fisk. I’m going home happy.”