Fenway Park (24 page)

Authors: John Powers

When Culberson had to chase Harry Walker’s looping liner, Slaughter took off on a mad dash around the bases. Culberson’s throw to Pesky was weak enough (“He threw me a lollipop,” the shortstop said decades later) that Slaughter decided to risk going all the way. “All I kept seeing was the World Series ring on my hand,” he said. How long Pesky held the ball has been barstool debate fodder ever since. The

Globe

’s Nason said that Pesky “froze momentarily” and Pesky readily took responsibility. “I’m the goat,” he said. “It’s my fault. I’m to blame. I had the ball in my hand. I hesitated and gave Slaughter six steps. When I saw him, I couldn’t have thrown him out with a .22.”

After Brecheen shut down Boston in the ninth for his third victory of the Series, he was borne aloft by his triumphant birds of a feather. The Sox dressed quietly in their clubhouse. “We lost to a great team,” concluded Cronin. But Williams, who wept in the shower and sat staring into his locker for a half hour, was inconsolable after hitting .200 for the Series. Boston Mayor James Michael Curley canceled his planned welcome-home reception for the club. “I guess the boys just simply aren’t in the mood for a reception, anyway,” he said. The railroad ride back to the Back Bay was somber. “This wasn’t just an ordinary train,” Harold Kaese observed in the

Globe

. “It was the Red Sox Special. It was a shield, bringing back to Boston a Red Sox corpse.”

The renaissance in 1947 came from the Yankees, who hadn’t won the pennant in four years and came out of the war disorganized and distracted, going through three managers in 1946 and finishing 17 games behind Boston in third place. Though the Sox were in second for most of the season, they dropped eight of nine games to fall eight games back on Independence Day and never were in contention again. With Ferriss, Hughson, and Harris all ruined by arm problems (they combined to win just 20 games), the rotation came apart and even Williams’s Triple Crown season (.343, with 32 homers and 114 RBI) couldn’t keep the Sox in contention.

As it was, early in the season Yawkey had come close to trading Williams to New York for Joe DiMaggio, which would have been the biggest one-for-one blockbuster in baseball history. But Boston also wanted catcher Yogi Berra, so Yankees owner Dan Topping nixed the swap. Yawkey did acquire a former Yankee icon, though, when he hired Joe McCarthy at the end of the season to succeed Cronin, who replaced Eddie Collins as general manager.

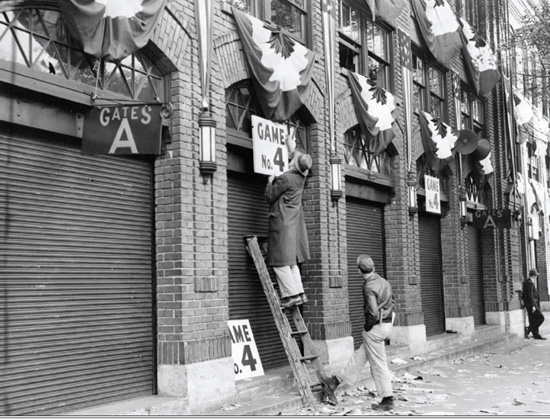

Workmen made sure everyone knew that Fenway would be host to Game 4 of the 1946 World Series.

“I’m going up with the real Irish now,” cracked McCarthy, who’d resigned from the Yankees for health reasons in May of 1946. McCarthy was 60 years old, but his résumé was top-drawer—nine pennants and seven Series championships with the Yankees and Cubs. “Now the Red Sox have as their manager a man who converses with gremlins,” observed Kaese, “instead of one who converses merely with knives and forks.”

So the front office soon made a deal with the St. Louis Browns, whose mascot resembled a gremlin, and brought in starting pitchers Jack Kramer and Ellis Kinder and shortstop Vern Stephens for cash and scrubs. Kramer and Kinder won 28 games between them in 1948, and Stephens led the club with 29 homers. Yet it wasn’t until after Memorial Day, when they were in seventh place and nearly a dozen games out, that the Sox came alive, winning 15 of 16 at Fenway in late July to move into first. “It took the Red Sox 98 days of the season to chin themselves into first place,” Kaese observed. “They have 70 left in which to elevate the rest of the body.”

Boston wound up in an enthralling pennant chase that came down to the final weekend with three teams in contention. The Indians, who were two games up with four to play, had the edge and the Sox needed to beat the Yankees twice at Fenway to force a playoff. “Nevertheless, if you can manipulate an Oriental abacus, you can still juggle the little wooden pegs and come out with a Red Sox victory,” Hy Hurwitz calculated in the

Globe

.

The Sox took care of one variable on Saturday when Williams, who’d been bothered by a head cold and had hit only one homer in six weeks, crushed a two-run shot in the first inning, spurring his mates to a 5-1 triumph and eliminating New York from the pennant chase. Then, as the Tigers were rocking ace Bob Feller en route to a 7-1 decision at Cleveland on Sunday, DiMaggio and Stephens each hit homers to rally the Sox to a 10-5 victory over the Yankees and set up the first pennant playoff in American

League history—a single elimination game against the Indians at Fenway the following day, October 4.

“We were counted out in the spring,” remarked McCarthy, as thousands of fans were mobbing the ticket windows for reserved seats and thousands more were lining up overnight for bleacher spots. “We were counted out as late as last Wednesday. But those players never gave up.”

The speculation was that Kinder, the most rested Sox starter, would face Cleveland’s Bob Lemon for the pennant. But Boudreau opted for left-hander Gene Bearden, a 20-game winner. Bearden would be pitching after just one day of rest, but his knuckleball was unhittable when it was behaving for him. McCarthy not only skipped over Kinder, he also bypassed Mel Parnell, who’d won 15 games and had the staff’s best ERA at home. Parnell was a southpaw and a rookie, which McCarthy concluded was a dangerous combination at Fenway with the pennant on the line and the wind blowing to left field. “Sorry, kid, it’s not a day for left-handers,” the manager told him. McCarthy instead went with a most unlikely starter in right-hander Denny Galehouse, a 36-year-old journeyman who had pitched only once since September 18.

Baffled, Boudreau had someone check to make sure McCarthy wasn’t warming up his real starter beneath the stands. Galehouse served up two homers, a solo shot by Boudreau and a three-run blast by Ken Keltner, while the knuckleballer Bearden bollixed the Boston hitters, allowing only five hits as Cleveland won, 8-3. “It’s pretty tough when you know what’s coming and still can’t hit it,” said DiMaggio.

Instead of the Sox facing the Boston Braves in the first Streetcar Series in the city’s history, the Indians went on to win their first championship since 1920, and Galehouse, who pitched only two more innings in his career, became a synonym for Sox failure for more than a half-century.

It didn’t seem possible that the Sox could lose a pennant in a more wrenching fashion, but they did just that in 1949. Once again, they staged a second-half surge. Once again, they played with the pennant on the line in the season’s final weekend against the Yankees.

That had seemed unlikely at the end of June when Joe DiMaggio, who’d been sidelined all season after heel surgery, swept Boston all by himself at Fenway in what he called the greatest series of his career. He hit a two-run homer and snagged Williams’s long ball for the final out in

a 5-4 victory in the Tuesday opener. He lifted up his pinstriped colleagues from a six-run hole with a three-run shot, and then hit another two-run homer in the eighth for a 9-7 revival on Wednesday. Then in the Thursday wrap-up game, DiMaggio hit a monster three-run blast off the left-field light tower in a 6-3 conclusion that brought a standing ovation from Sox fans who’d always claimed that Dom was the better DiMaggio. “You swing the bat and hit the ball,” Joe explained after he’d scored five runs, knocked in nine more and batted .455 for the series.

In April 1947, the pennant was hoisted at Fenway by (from left) MLB president Will Harridge, Red Sox manager Joe Cronin, and Ossie Bluege, manager of the Washington Senators.

After dropping a doubleheader in the Bronx on Independence Day, Boston seemed all but finished, sitting 12 games behind in fifth place. But the Sox went 42-13 in August and September to come storming back into contention. The season turned when the Sox won two pivotal games at Fenway to draw even with the Yankees. They took the first on Williams’s 42

nd

homer, a 410-foot launch into the right-field stands, and a daring dash by Al Zarilla, who scored from second after catcher Yogi Berra bounced a throw to first trying for a double play.

“It was a chance and I took it,” said Zarilla, who’d been picked up from the Browns in May. After Parnell had mystified the visitors for a 4-1 victory on Sunday, the Sox proceeded to New York, where they claimed first place after Doerr squeezed home the winning run in a 7-6 bleeder.

They were back at the Stadium for the endgame, with the Sox ahead by a game with two to play and hundreds of their fans already lining up on Jersey Street for Series tickets. But the Sox squandered a 4-0 lead in the opener of the double-header and lost on a homer to left by light-hitting Johnny Lindell that just went fair. Then, with his club trailing, 1-0, after seven innings in the finale, McCarthy pinch-hit for Kinder, came up with nothing, and then watched New York score four in the eighth on a solo homer and a three-run bloop double by Jerry Coleman. The Yankees went on to win, 5-3, and take the pennant. “Too bad we had to do it to you,” his former Yankees players told McCarthy when he went over to his old clubhouse to congratulate them.

The train ride back to Boston was a funeral cortege and the players were greeted at the station by mourners who’d been at Fenway hoping to snap up World Series tickets. “If we can’t win one out of two, we don’t deserve it,” Yawkey said. But it would be another 18 years before his players would come that close again.

The bullpen had plenty of company on October 4, 1948, when the Fenway faithful packed the bleachers to watch the Red Sox face the Indians in a one-game playoff. They were stunned when Cleveland won the game, 8-3.