Fighting to Lose (29 page)

Authors: John Bryden

Huge columns of black smoke billow from the battleships USS West Virginia and USS Tennessee minutes after being hit by Japanese bombs and torpedoes on December 7, 1941.

Huge columns of black smoke billow from the battleships USS West Virginia and USS Tennessee minutes after being hit by Japanese bombs and torpedoes on December 7, 1941.

NARA

Churchill and Roosevelt were to get their wish: Hitler joined his ally and declared war against the United States on December 11.

Churchill and Roosevelt were to get their wish: Hitler joined his ally and declared war against the United States on December 11.

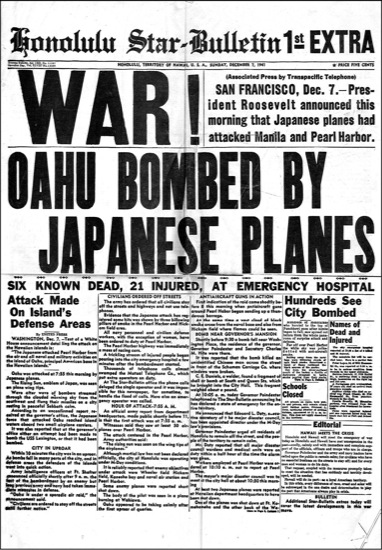

Honolulu Star Bulletin

12

July–August 1941

Churchill wanted war between the United States and Germany, and by the summer of 1941 he had a good idea how he might achieve it: Get Roosevelt to provoke the Japanese into attacking America.

At stake was Britain’s survival. Hitler’s lightning invasion of the Soviet Union in June had diminished the likelihood of a cross-Channel attack and the bombing of British cities had eased, but it all would come back again when Hitler turned his full attention on England once more — perhaps even later that year, considering the rapid collapse of Stalin’s armies. Indeed, with the toll German U-boats were taking on British shipping in the Atlantic, Hitler might not even have to invade. The country could starve to death.

The only hope was the United States. Throughout the previous year, President Roosevelt had been sympathetic, but guardedly so. Isolationist feelings ran deep in America, fuelled by the America First Committee and a powerful congressional lobby led by Senator Burton K. Wheeler. With opinion polls saying that 88 percent of Americans opposed joining the war in Europe,1 and with the prospect of mid-term congressional elections always in mind, Roosevelt had to be sparing and careful in his help to Britain. Germany, meanwhile, was doing everything it could not to cause offence.

That left Japan. If Churchill was to see the United States drawn into the fight with Germany, the war had to go global.2

Japan’s transition from a closed, quasi-feudal society in the 1850s to a modern military power in barely three generations is one of the social miracles of the modern era. First there was war with China, and then, in 1905, using tactics, weapons, and technology borrowed from Europe, and British-built battleships, it decisively defeated czarist Russia in the struggle for control of Korea. By the late 1930s, it had a huge army, was again engaged in war with China, and had a fully modern fleet, complete with aircraft carriers, the equal to any on the oceans, the Japanese thought, and a match for the Americans and British in everything but numbers.

It was a first-class naval weapon forged by an island nation for exactly the same reason that Britain needed the Royal Navy: to police an empire of colonies and vassal states whose raw materials and commerce would feed the mother country. The problem was, the empire that Japan desired in the Far East was already mainly owned and occupied by the British, and, to a lesser extent, by the French and the Dutch.

The United States, in contrast, was not Japan’s natural enemy. Other than the Philippines, it had no significant possessions in the Far East west of the islands of Hawaii, and Hawaii was too far away to be coveted. Besides, Japan’s industries relied heavily on the United States for scrap iron, oil, and other commodities, and there was both respect and affection for the Americans for having been first to help open the country to the world.3

The French, Dutch, and British, on the other hand, had to be fought sooner or later, and when France and Holland were overrun by Hitler, the Japanese felt that the great opportunity had come. Fending off air attacks at home while engaged in desperate struggles in the Middle East and the North Atlantic, Britain had no significant air or naval forces to spare to defend its possessions in the Far East. Churchill could only hope that when the inevitable clash came, it also somehow pulled in both the United States and Germany.4

For a moment Hitler himself seemed to provide an opening. In September 1940, he persuaded Japan into signing the Tripartite Pact, which, among other things, included a clause whereby should Germany, Italy, or Japan be attacked by any nation not already involved in the European War, the other two would come to its aid.5 Over the next eight months, Churchill tried to obtain a similar arrangement with the United States, whereby should Britain become embroiled with Japan in defence of its Far East possessions, the Americans would automatically join in. It was a futile hope. Roosevelt made it clear that no president could hope to sell war to Congress in order to save Britain’s empire, and only Congress had the constitutional right to declare war.

Then, with Hitler’s invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the prospect of Japan advancing on the British seemed to recede. Attacking the Russian behemoth from behind, in Siberia, offered Japan an interim target for its expansionist aims, and one that was handy to its army already in northern China. The world, and especially Britain, waited for Japan to do the obvious.

At the beginning of August, just before the British double agent Dusko Popov was to leave Lisbon for the United States, his German controllers gave him a long list of questions on a series of microdots, many of which dealt with the air and naval defences of Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, home to the U.S. Pacific Fleet.

Only eight months earlier, in one of the most daring and original British exploits of the war, obsolete, canvas-and-glue Fairey Swordfish torpedo bombers launched from the aircraft carrier

Illustrious

made a highly successful surprise attack on the Italian naval base at Taranto, sinking three battleships and doing much other damage. The Japanese had six fleet carriers, each with greater aircraft capacity than the

Illustrious

and better carrier-borne fighters and bombers.

When members of the XX Committee and other officers at MI5 eventually saw the questionnaire, it was plain to them that the Abwehr’s help had been sought because the Japanese were considering a similar attack on Pearl Harbor.

The incident of the so-called TRICYCLE questionnaire was first described thirty years later by J.C. Masterman, in his book

The Double-Cross System

, and he excoriated the Americans for having ignored the obvious when Popov turned over the microdots on arrival in New York. “It is therefore surely a fair deduction,” he wrote, “that the questionnaire indicated very clearly that in the event of the United States being at war, Pearl Harbor would be the first point to be attacked, and that plans for this attack had reached an advanced state by August, 1941.”6 Two years after Masterman published his book, Popov himself, in

Spy/Counterspy

, depicted an oafish J. Edgar Hoover letting slip from his grasp the opportunity to alert the president and spare America from the “Day of Infamy,” the December 7 surprise attack that devastated the U.S. Pacific Fleet, sinking four out of eight battleships and damaging the rest.

Other veterans of wartime British intelligence took up the refrain: “When coupled with the Japanese special interest in the raid on Taranto it seems incredible that Pearl Harbor should not be on the alert for a surprise hit-and-run air raid,

if

Hoover had not failed to pass on what TRICYCLE brought him,” said Lieutenant-Commander Ewen Montagu, the Royal Navy’s representative on the XX Committee.

MI5’s double-agent chief “TAR” Robertson’s condemnation was even more severe: “The mistake we made was not to take the Pearl Harbor information out and send it directly to Roosevelt. No one ever dreamed Hoover would be such a bloody fool.”7

These were harsh words, and they deeply rankled those in the American intelligence services. Hoover was never lovable, but his commitment to the Constitution and to the Office of the President is still legendary. The British portrayed him as venal and stupid.

The FBI, it should be said, was a victim of its own sense of responsibility to maintain the confidences entrusted to it. When, in 1989, retired CIA officer Thomas Troy rose to Hoover’s defence in a closely argued article entitled “The British Assault on Hoover: The Tricycle Case,” he had to rely on FBI case-file documents that had been heavily redacted, with all references to British intelligence removed. Troy’s arguments, though authoritative and logical, were crippled by lack of evidence.8

Troy, and an earlier British critic of the MI5’s extravagant double-agent claims, David Mure, began with the premise that if the threat implied by Popov’s questionnaire was so obvious, why didn’t someone in authority in Britain warn the Americans directly? Why leave it exclusively to an agent to deliver information of such importance, and why deliver it to an American civilian agency rather than to the military authorities, or, for that matter, to the U.S. secretaries of state, war, or the navy? Hoover’s British critics simply ignored the question and neither Troy nor Mure could come up with satisfactory theories of their own.9

Two years later, when the relevant documents reached the half-century mark, the FBI released them with their content restored, but too late: the wave of interest had passed. However, some twenty-five years later, combined with the declassifying of certain MI5 files in Britain, they permit the piecing together of a truly remarkable story.

It begins with Churchill. He had been an enthusiastic promoter and user of secret intelligence for years, especially during the First World War. He thrilled to tales of espionage and was one of Britain’s early champions of code- and cipher-breaking. He certainly would have relished the centuries-old tradition that a nation’s spy chief directly serves the head-of-state — monarchs in the Middle Ages, and prime ministers, presidents, and dictators in the twentieth century. This was not something that he was going to miss out on when he became prime minister, and “C” — Stewart Menzies, chief of MI6 — reported to him daily, usually in person.