Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (10 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

“Actually, I’ve read it many a time,” he said. “I just didn’t have the same interpretation.”

“Here, let’s read it and let’s see how you might interpret it differently,” I said. “What it says is: ‘The value of investments of public securities is determined using quoted market prices discounted for illiquidity or restrictions on resale.’”

“Is there a sentence after that?” he asked.

“No.”

“Well, I’ll tell you what. I’m going to go back and read the whole thing.”

“I think, if you’re mistaken, I think you should publicly correct it,” I said.

“I think if I’m mistaken, I should publicly correct it.”

A week later, after I followed up with Hughes’s boss, Merrill published a follow-up acknowledging, “We were mistaken. The audit guide changed in May 1997.” But they did not admit or correct their error that Allied isn’t supposed to mark its portfolio to “long-term value” or that it can’t carry publicly traded securities above their quoted prices.

During the weeks following the speech, I received phone calls and e-mails from long and short investors who were trying to understand both sides. Many contacted Allied, as well. Even when the e-mails had an edgy tone, I tried to respond matter-of-factly. Through these dialogues, we kept up with Allied’s latest spin, and I believe they kept up with our views. Through these intermediaries, we debated without direct contact.

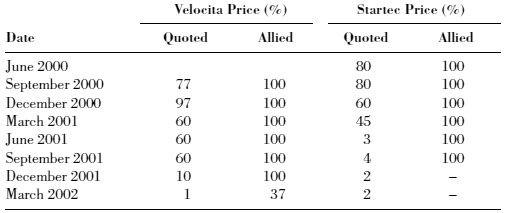

At Greenlight, we continued our research. We gathered the historical bond prices from Chase Securities for Velocita and Startec and compared them to Allied’s historical carrying values. As

Table 7.1

shows, Allied did not take timely markdowns.

Table 7.1

Velocita and Startec Bonds

Allied structured its loan to Startec to be

pari passu

with Startec’s bonds. That means that even though they owned a separate piece of paper, it had the same status as the bonds. As a result, the bond price was a good indication of value. If anything, under SEC rules, Allied should have carried its investment at a discount to reflect the relative illiquidity of its private investment.

One fund manager sent us a copy of a recent BLX securitization prospectus. It showed that 14.5 percent of BLX’s loans were delinquent as of December 31, 2001. We called the credit rating agencies to learn more about BLX’s securitizations. The agencies told us that they got the data used to rate the securitizations from BancLab, which tracked Small Business Administration loans. We licensed BancLab’s analysis of BLX’s portfolio. It would take them about a month to prepare a report.

CHAPTER 8

The You-Have-Got-to-Be-Kidding-Me Method of Accounting

Just two weeks after the speech, Allied held a second conference call on May 29, 2002. Walton came out firing. “We understand [our business] better than any external individual, and we are going to continue to communicate our understanding to you,” he said. “But let’s be clear: We are not having an academic, intellectual debate. The shorts are people with an agenda and a lot of money and reputation riding on trying to get investors to deconstruct our company and to view the Allied Capital glass as half empty.”

Allied first tackled the Audit Guide problem. The company conceded that its argument about the Audit Guide changes was false and acknowledged that the Audit Guide, in fact, changed in 1997. Now, Sweeney asserted on her honor that Arthur Andersen had not identified any problems with the audit. Andersen had shut down due to Enron-related liability, and Allied had just hired a new auditor. Though we will never get to the bottom of why Andersen changed the language, we know Allied’s first explanation was a lie. In any case, whoever opined that Velocita debt was worth par at the end of 2001 didn’t do much of an audit.

Walton continued the call with a valuation discussion. “The other issue is that shorts seem to think that we should write loans down to zero at the slightest sign of trouble, regardless of whether there has been money lost,” he said. Obviously, we don’t believe that loans should be written to zero at the slightest trouble. Walton is smarter than that. Finally, he repeated what Roll told us, “We write loans down to the amount that we believe we will collect.”

Larry Robbins of Glenview Capital pressed the company about the carrying values of troubled credits. Roll explained, “Sure, Grade 3 assets, really we don’t see any real risk of principal or interest loss in what we call [loans] in ‘monitoring.’ In other words, we’re working with the company, and it can be a Grade 3 for a variety of reasons. They can be a Grade 3 because they’re working on something with their senior lenders, they can be a Grade 3 because we’ve had companies go into Grade 3 because we’re working with them and they’re up for sale and, as a result, [they’re not paying us] for whatever reason until they sell. But they can be a Grade 3 for a variety of different reasons.

“Grade 4 is where we get a lot more concerned, because Grade 4 we think we’ve lost contractual interest due to us. In other words, the deal we went into with respect to what they were supposed to pay us in interest, we don’t think we’re going to get that contractual interest. Now, we don’t think principal’s impaired, but we do think we have contractual interest loss. Grade 5 is where we think we’ve not only lost contractual interest, but we’ve actually lost principal. And this is principal, so it’s cost basis. In other words, it’s money that went to them that we don’t think we’re going to collect back. So if an asset is in that situation, [it] is a Grade 5.”

Robbins persisted. “But your carrying values of Grade 4, for example, there is a likelihood that you would not receive guaranteed interest, but you would still receive contractual principal. Where are you carrying those Class 4 loans?”

“It depends on the asset, but most of those would be carried at original cost and . . .” Roll said.

“So, it’s only a Class 5 loan that would get written down below cost?” Robbins asked.

“Right,” she said.

Here we are back to day one of freshman investing class, where beginning students learn that when an investment reaches a stage where the investor would not repeat the investment, it is no longer worth the original cost. As a result, loans to companies performing below plan, violating covenants, or even not making interest payments—including to the point that Allied realized it would never collect the interest—are not worth cost. Nonetheless, if Allied believed it would eventually recover its principal (Grade 4), it valued the investment at cost. This might be called the “

you-have-got-to-be-kidding-me”

method of accounting. Walton wanted people to believe that we thought loans needed to be written down to zero at the first sign of trouble. What we believed was that these loans might be worth more than zero, but they certainly were not worth 100 cents on the dollar, as Allied’s financial statement indicated.

Sweeney then introduced a white paper (essentially a research paper) that she and Roll authored describing Allied’s valuation strategy. “We have a consistent process we’ve used to determine fair-value, and that process is clearly outlined in our disclosure document,” Sweeney said. “In addition, if you visit our Web site, you will see that we have written a white paper on fair-value accounting and our interpretation of its application. We wrote this paper for a conference on BDCs in February. We encourage you to read the white paper to obtain a better understanding of fair-value.”

Investors didn’t need to read Allied’s white paper to learn about fair value. It’s not up to Allied; it’s up to the SEC. In 1969 and 1970, the agency issued accounting series releases (ASRs) describing how investment companies need to value investments. ASR 118 says, “As a general principle, the current ‘fair-value’ of an issue of securities being valued by the Board of Directors, would appear to be the amount which the owner would reasonably expect to receive for them upon their current-sale.” Then, it elaborates on how to value both marketable and unmarketable securities. ASR 113 indicates it is improper to continue to carry securities at cost if cost no longer represents fair-value as a result of the operations of the issuer, changes in general market conditions, or otherwise. Furthermore, investment companies have to take into account restrictions on selling when determining fair-value.

Shortly after the conference call, I did as Sweeney asked. I downloaded the white paper,

Valuation of Illiquid Securities Held by Business Development Companies

. It comes right out and challenges the SEC-issued ASRs. It argues, “The concept of ‘current sale’ in ASR 118 is particularly troubling if applied to a BDC’s illiquid portfolio, because if such a portfolio were subject to a current sale test, the portfolio would need to carry a significant discount from the face value of its underlying securities.” The white paper continues, “The concept of current sale for the purposes of determining fair value in ASR 118 is difficult, if not impossible, to apply in the case of a BDC’s portfolio.”

The paper boldly asserts, “The current SEC regulations and interpretive advice for valuing a security at fair value applicable to investment companies [is] . . . not specifically applicable to BDC’s.” Further, according to the paper, the SEC-mandated rules “are not easily applied to the unique characteristics of a BDC portfolio, primarily because the securities in which a BDC invests cannot be put to the test of current sale for purposes of valuation.”

So, according to Allied, the SEC rules don’t apply to the company. Indeed, if it had to follow the SEC rules, which require the current-sale test, the company’s portfolio would have to be carried at a significant discount. In fact, Allied conveniently said that a current-sale test is too difficult to employ because the securities are illiquid.

The white paper brazenly flaunts Allied’s use of non-SEC-sanctioned accounting. Instead, it calls for more lenient SBA accounting. Under SBA methods, assets are written down only when they are deemed to be permanently impaired. “SBA policy is far more applicable to the portfolio of a BDC than the valuation guidance set forth by the SEC in the ASR’s,” the white paper explains in alphabet-soup fashion.

The conclusion of the paper could not have been clearer. “SBA policy, with minor modifications, appears to provide the best overall guidance for valuation of fair value for the portfolio of a BDC . . . BDCs, therefore, should adopt investment policies that encompass the guidance provided by the SBA, taking into account that all private illiquid securities may have unique characteristics that impact value.” I have never before or since seen a company publicly indicate that it ignores SEC rules.

Somehow, Allied did this without fear of repercussions

.

After producing the white paper, Sweeney said on the conference call that Allied isn’t a normal investment company and investment company accounting should not really apply to it. She indicated the public markets don’t value BDCs at net asset value, but rather based on dividend yield. While they are subject to the Investment Company Act of 1940, they are different from mutual funds because they are “internally managed operating companies” and don’t report results like mutual funds, but, instead, file 10-Qs and 10-Ks like operating companies.

Sweeney continued to explain why Allied shouldn’t be viewed as an investment company:

“What we do think is important to our valuation as a public company is our net income, which communicates our earnings power to shareholders. The idea that we should be marking long-term, illiquid investments to some artificial or theoretical market instead of telling shareholders what we really think we have made in gains or lost in principal seems theoretical at best and at least confusing. We don’t hide what we’ve lost by claiming a temporary decline in market. When you read our income statement and look at net income, you know where we think we actually are and don’t think it serves any purpose to cloud our results with a lot of temporary unsustainable ups and downs.

She continued, “Net income is the predictor of future dividends for shareholders. [Investment losses] will decrease dividends; real investment gains will increase dividends. Mutual funds trade in the public markets at net asset value, and they mark their portfolios daily because they are simply pools of securities that have a value that is shared by the fund’s shareholders. Mutual funds are typically externally managed. Mutual funds must stay very liquid and be very precise on their net asset value calculation, because they are subject to daily redemptions should their investors take money out of the fund by selling their shares. Net asset value is the primary method by which mutual funds trade. In contrast, Allied Capital, like most BDCs, invests in long-term illiquid securities. Any increases in value are realized over a long period of time. BDCs typically do not trade their securities; they invest until maturity or until ultimate sale of the company that has issued the securities. BDC shares are not subject to redemption.”

Allied’s 2001 annual report issued in early 2002 echoed Sweeney’s conference call statement, Roll’s private description, and the white paper’s thesis. For example, Allied’s official policy stated, “The company’s valuation policy considers the fact that privately negotiated securities increase in value over a long period of time, that the Company does not intend to trade the securities, and that no ready market exists. . . . The Company will record unrealized depreciation on investments when it believes that an asset has been impaired and full collection for the loan or realization of an equity security is doubtful.”

This, cleverly enough, is the SBA standard for valuation. But as a regulated investment company, Allied is subject to the tougher SEC standard that requires write-downs as soon as a willing buyer would no longer pay cost.

The 2001 annual report continued to echo Sweeney’s conference-call statement: “Under its valuation policy, the Company does not consider temporary changes in the capital markets, such as interest rate movements or changes in the public equity markets, in order to determine whether an investment in a private company has been impaired or whether such an investment has increased in value.”

Oddly, though, the previous year’s annual report lacked most of this language. Clearly, it was brand new in the 2001 report. Obviously, this could not be part of Allied’s forty-year-old “consistent” accounting practices. The new language plainly reflected new practices, with new prose now justified by the white paper. Had Allied modified its accounting policy to avoid taking write-downs in the mini-recession of 2001–2002?

Later, we learned that the white paper wasn’t Sweeney’s first attempt to obtain lenient SBA-styled accounting treatment for BDCs. In 1997, Sweeney represented Allied in the SEC’s annual Government-Business Forum on Small Business Capital Formation that recommended, “[a] safe harbor . . . be established in the ‘40 Act for the ‘mark-to-market’ evaluation of investment companies’ portfolio of illiquid investments in small businesses to protect directors of such companies from possible liability.”

The panel elaborated: “The Investment Company Act requirement of [sic] that fund boards determine the ‘fair value’ of portfolio securities for which market quotations are not readily available discriminates against the illiquid securities typically issued by smaller companies. Using an established valuation guideline such as the one developed by the SBA should provide sufficient information and consequently some protection for the investment company’s directors from liability under federal securities laws.”

The SEC never granted the requested safe harbor.

In summary, Sweeney went to the SEC and asked permission to use the SBA standard. When the SEC didn’t agree,

Allied did it anyway

. Then, Sweeney and Roll wrote a white paper to justify it. In 2004, when we learned of Sweeney’s 1997 failed attempt with the SEC, I realized Allied’s improper use of SBA accounting was no accident. Rather than an unsophisticated lack of understanding, it was a willful, intentional act—a sham that had been in the works for years.