Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (13 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Sweeney repeated the eleven-year loan life number at an investment conference sponsored by Bank of America on September 22, 2002. In 2003, Wachovia Securities published a report estimating BLX average loan life to be less than four years. Since one of the key assumptions in calculating the gain-on-sale is to estimate the life of the loans, if BLX assumed eleven years, then it dramatically overstated its revenues because the longer the term, the more interest payments are assumed to be paid. (If BLX used an assumption that was closer to four years, then Sweeney was misleading the market.) Its gain-on-sale assumptions remain top secret to this day. Incidentally, if Allied consolidated BLX, it would have to disclose the assumptions.

During the call, Allied said that Hillman had made a typographical mistake in the 10-K and Hillman’s senior debt was worth face value. The point refuted our analysis that Allied’s subordinated investment in Hillman was not worth par, because Hillman’s 10-K conceded that the fair-value of Hillman’s senior debt was only 75 percent of face value. We believed that if the senior debt wasn’t worth face, the subordinated investment wasn’t worth face, either.

We, of course, had assumed Hillman had filed an accurate report with the SEC. Indeed, in my next letter to the SEC, I wrote, “In our earlier analysis, we had relied on that disclosure in asserting that Allied’s investment in Hillman was impaired. Assuming that it was in fact a typo, we would withdraw the criticism based on their erroneous SEC disclosure. We would, however, continue to assert that the 18 percent rate of interest Allied charges Hillman is not arm’s-length or market and should not be permitted.”

Before Allied bought Hillman, it advanced an unsecured subordinated loan at 13.9 percent interest, while Hillman’s publicly traded preferred stock yielded 19 percent. By the time Allied obtained control, Hillman’s credit improved so that the preferred yielded only 12 percent. Nonetheless, Allied reset the rate it charged Hillman to 18 percent, increasing Allied’s reported interest income. A fair rate on a subordinated loan should be lower than the prevailing yield on the preferred equity. However, as Allied controlled Hillman, it set the rate as it saw fit. Though Allied eventually sold its equity investment in Hillman for a large gain and claimed vindication, Allied gave Hillman a new subordinated loan at a market rate of 10 percent, further confirming our view that the earlier 18 percent rate was not arm’s length.

More inaccuracies followed. Sweeney spoke about Galaxy American Communications (GAC) and explained that GAC, in which Allied held an investment valued at $39 million compared to the original cost of $49 million, was a different company from its affiliate company, Galaxy Telecom, which had gone bankrupt. She said the criticism of GAC was, “bogus . . . almost comically bogus.”

“It appears that our critics not only don’t do simple math, but they don’t do their simple homework,” she said, castigating us. “Is it possible that our critics, so quick to accuse and so oblivious to our facts, had confused these two companies? Or without evidence, are suggesting that the adverse results of Galaxy Telecom has [sic] any impact on the financial results of Galaxy Communications? Apparently so, which tells us all about their credibility.”

We hadn’t said anything about GAC. The only applicable comments we knew about came from

Off Wall Street

, which was certainly not confused. It clearly distinguished between GAC and Galaxy Telecom in its report. Since the vast majority of listeners did not have access to

Off Wall Street

, they would be unable to see that Sweeney was just making this up, with a fabricated attack on our “math,” “homework,” and “credibility.”

After several questions by brokerage firm analysts and sympathizers, one caller asked, “I’m just wondering whether you’re going to take some calls from the so-called shorts you’re complaining about.” To which, Sweeney’s reply was basically, “the line is open.” Once again: untrue. On this and the previous conference call, I tried to get into the queue to ask questions. Though the calls went for a long time, Allied did not take a question from me. The service that operates the conference calls provides the company with a real-time list of who is on the call and who is interested in asking questions. The company determines whose questions will be accepted, and no one gets through without its consent.

Sweeney added another untruth for good measure: “We’ve never had a call or visit from the two organizations who have written papers about us.” I couldn’t believe that Sweeney still claimed we had never called Allied. According to a

Dow Jones Newswire

story, “Allied Capital: Short-Recommendation Reasons ‘Unfounded’” (May 16, 2002), “The Company confirmed that investor relations director Sparrow and Chief Financial Officer Penni Roll both had spoken to the hedge fund manager [me] within the last month.” Despite this, Sweeney

again

insisted we never called. I continued to hear this lie repeated for years.

The next question related to my conversation with Doug Scheidt, the SEC official, which we detailed in the analysis on Greenlight’s Web site. Sweeney answered, “If you look at the question and answer between Doug Scheidt and I guess it was Mr. Einhorn, Doug answered the questions that were asked. They weren’t the right questions. The way Mr. Einhorn characterized what we do is not, in fact, what we do. So, if he wants to put a hypothetical in front of Doug Scheidt and get an answer, that’s one thing. But it’s not specifically Allied Capital.”

There was no dispute: I conducted my conversation without identifying Allied. However, we discussed what Allied said and wrote, and Scheidt responded that it was “inappropriate.” Sweeney knew this and, in my opinion, was kicking dust in the air.

A couple of days later, on June 19, Allied issued a press release announcing that Sweeney had met with Scheidt, who confirmed the conversation had been generic. Sweeney never revealed what else she and Scheidt discussed during their meeting. Did Allied ask Scheidt to comment on the white paper and accounting policies, and what did he say? Did the conversation with Scheidt cause Allied to change its description of its accounting methods, which it did in its next SEC filing? Had the answers to these questions been exculpatory to Allied, I believe Allied undoubtedly would have shared more details of Sweeney’s conversation with Scheidt in the press release.

At the end of the June 17, 2002, conference call, Walton promised to disclose more information about its control companies, including BLX’s gain-on-sale accounting assumptions. He said, “It’s the right thing to do.” And, of course he was correct that it was the right thing to do. Subsequent events, once again, revealed his unwillingness to do the right thing. Though Allied began providing summary information on BLX in the next 10-Q, it never revealed the promised detail on gain-on-sale, and Allied never provided more information about its entire portfolio of controlled companies, as Walton pledged.

Allied’s stock, which began to fall again after the

Off Wall Street

report, fell further, reaching $20 per share following the conference call. A few days later, Sweeney decided to turn up the volume on her personal attacks and said in a

Bloomberg

article that our plan was a strategy of “let’s scare the little old ladies.”

I told

The Washington Post

at the time, “We’re not critical of this company because we are short; we are short because we are critical of this company.” Ladies, be they little, be they old, or be they both, had nothing to do with it.

CHAPTER 10

Business Loan Express

In early June 2002, I heard from Jim Carruthers, a partner then at Eastbourne Capital Management in San Rafael, California. I had met him nine years earlier while working on my first short sale of a fraudulent company, Home Care Management, while at Siegler, Collery. Carruthers was a

digger

, an analyst who developed alternative sources and searched public records to gather valuable information not generally contained in press releases.

During our conversation, Carruthers told me he had discovered fraud at Business Loan Express, Allied’s largest investment. At March 31, 2002, Allied carried BLX at $229.7 million, or 17 percent of Allied’s net asset value. Furthermore, Allied had additional exposure through its guarantee of BLX’s bank debt. Again, Allied formed BLX by purchasing BLC Financial Services Inc., a publicly traded company, and combining it with its own SBA lending business, Allied Capital Express. (As I describe the various troubling and sometimes fraudulent BLX loans throughout this book, I am referring to BLX or either of its two predecessors.)

Carruthers identified BLX’s SBA loans that were the subject of court proceedings by searching through PACER, a legal database. He obtained the related filings and spoke to a number of the participants. One case related to loans extended to a woman named Holly Hawley for car washes in Michigan that, according to Carruthers’ interviews, “violated every convention and lending practice.”

Carruthers found that Hawley had previously been criminally charged and convicted of a federal crime involving the illegal conversion of Federal Housing Administration property in an embezzlement case. Carruthers found a transcript of Hawley’s sworn testimony that detailed her experience with BLX. To summarize: Prior to obtaining the loan from Allied, four banks cited her lack of operating experience—a requirement to obtain an SBA loan—in denying her application for construction loans to build car washes. Hawley’s loan broker introduced her to Allied (prior to the formation of BLX), which issued her an SBA loan. Hawley wanted to obtain more financing to build additional car washes, but was ineligible to borrow from the SBA, which permitted only one loan per person. Because she was “loaned up” at the SBA, Allied suggested that she form a new corporation and use her brother to sign the loan documents.

Hawley’s fraudulent loans were made and supervised by Allied executive vice president Patrick Harrington and vice president William Leahy. Harrington headed the Detroit office of BLX in Troy, Michigan. After Hawley’s two SBA loans defaulted, Harrington and Leahy tried to cover up the loss by granting her additional loans. She formed yet another entity to take another loan and used the proceeds to pay $150,000 of past-due interest owed on the existing SBA loans and pay off liens filed by contractors.

Allied instructed her to put the loan into her twenty-year-old daughter’s name, and Hawley even bought an airline ticket for her daughter to attend the closing. However, an employee at Allied’s Washington, D.C., office rejected the loan due to her daughter’s inexperience and status as a full-time student. Allied suggested that Hawley issue the loan to yet another brother, who lived in California. She signed her brother’s name at Allied’s office in Leahy’s presence, at his direction.

Carruthers found another dubious loan to Jefferson Fuel Mart, a gas station in Detroit. According to his interview with one of the attorneys involved in the case, BLX entered into a loan that was “wholly inappropriate given the asset and cash flows associated with the property,” on which BLX appeared to “conduct zero due diligence.” The appraisal was so inflated, at about three times the actual value of the property, as to suggest fraud. The borrowers who were given the loan had no business experience. Apparently, they bought the gas station from one of the borrowers’ brother, who had run into trouble with loan sharks. The borrowers never made a single payment on the loan, but BLX waited a year and a half before attempting to collect on the default.

In the related litigation, it was alleged that, “Allied Capital Corp. delayed for a year and several months in collecting or bringing any action on the defaulted ‘loan’ for the reason that they did not want their stockholders and investors to discover the nature of this bad loan and the inadequate collateral underlying the loan.”

Prior to forming BLX, Allied made a loan to Victor Lutz, who planned to expand his hotel in Michigan with a “funland” and a bakery restaurant. According to Carruthers’ interview with Lutz, Lutz informed the loan officer before the closing, “We’re having a real rough time right now” because the road leading to the hotel had closed. Lutz asked whether the loan would “stay with him, because we may miss a few payments because of these issues.” According to Lutz, the Allied loan officer said not to worry, they would understand if he fell behind. Lutz defaulted.

In addition to these anomalies, Carruthers also found a firm called Credit America, a third-party business loan broker operated by Kevin J. Friedrich out of his home, that was doing business with BLX. Carruthers discovered that Friedrich had been investigated and sanctioned by the Pennsylvania Securities Commission and the National Association of Securities Dealers for various securities laws violations. According to Carruthers’ source, Credit America generated $40 million of loans per year for BLX.

Carruthers also found several other loans that appeared to have significant problems. My immediate reaction was, “So what?”

BLX was just one piece of Allied Capital, and these loans represented only a small piece of BLX. I didn’t see how a handful of bad SBA loans could make a difference in view of what we perceived to be the much larger and broader problems at Allied itself.

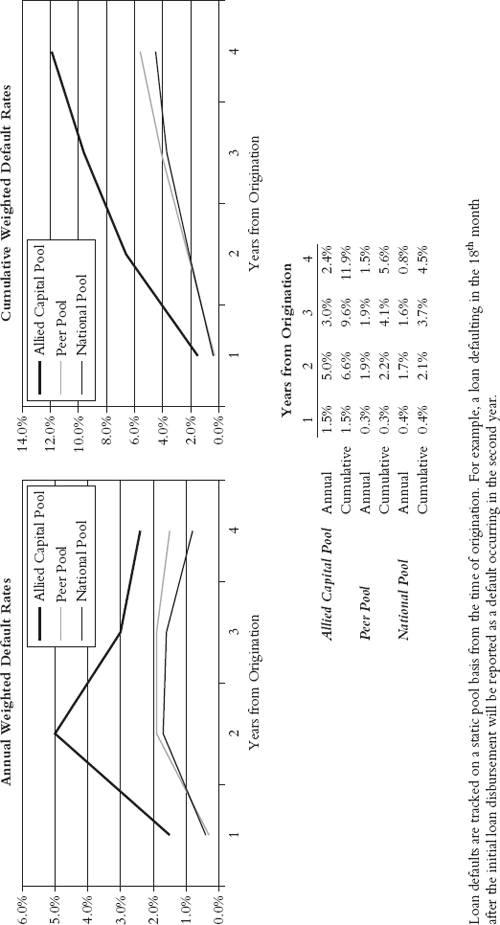

Yet, a few days after we published our research on Allied, we received the BancLab report. It showed that BLX’s portfolio performed far worse than we imagined. BLX’s loans defaulted about three times more often than the average SBA loan. Even after adjusting the loans for age, size, geography, industry, and other factors, BLX’s loans defaulted more than twice as often (see

Table 10.1

). I hypothesized that the excess defaults at BLX reflect its aggressive or even fraudulent underwriting practices.

Table 10.1

Average Annual Default Rates from BancLab Report

Carruthers told us that he shared his findings with the SBA’s Office of Inspector General (OIG), which is responsible for internal audit and investigations for the agency. He asked if we would speak with the OIG and I agreed. A few days later, Keith Hohimer called from the SBA’s OIG and said he was looking into BLX. I didn’t have anything to tell him separate from what Carruthers found. I sent him the BancLab report at his request.

On June 26, 2002, a former employee of BLX, who read our analysis of Allied on Greenlight’s Web site, e-mailed me. He identified himself as a former senior vice president of BLX who had previously been at Allied Capital. He wrote that he “left in October 2001 because I was basically forced to resign by BLX’s new management team due to the fact that our secondary market loan sale premiums declined so significantly.”

The reason for the decline was principally due to the poor performance of the loan portfolio, as you noted. As a result, BLX was forced to establish its own securitization facility to sell the unguaranteed portion of their SBA and 504/piggyback loans. This eliminated my position with the company.

The CEO wanted me to leave because I often pointed out the massive underwriting deficiencies to Allied’s executive management.

In my three years at Allied I was promoted annually by Joan Sweeney and I was given the highest possible rating an employee could achieve in my annual review the last two years. My raises and bonuses exceeded 20%. In other words I was an outstanding employee and thus a very credible person to speak with concerning Allied.

Although I have not covered any new information in this e-mail, I would be willing to meet with you in order to give you some critical additional insight that would be valuable information regarding BLX . . . that you may not be aware of. If you are interested, please let me know the next time you are in the D.C. area.

I never met him, but we spoke on the phone and he had more damning things to say. He said BLX focused on issuing as many loans as it could, as fast as it could, so that it took severe shortcuts in underwriting loans. According to him, BLX management consciously de-emphasized underwriting by installing underwriters with “no lending experience.” BLX did not properly check a borrower’s creditworthiness or collateral. Most notably, BLX did not verify that each borrower had invested equity in the business (called an “equity injection”), which is a basic SBA lending requirement to ensure that the borrower had “skin in the game.” As a result of all this, BLX experienced increased loan defaults.

The former employee said BLX developed the reputation for selling shoddy loans that went into early default. He said BLX used accounting assumptions on these loans “that were crazy” because they relied on outdated historical information on the average life of its loans that failed to account for the more sophisticated nature of today’s borrowers, who are more likely to refinance with cheaper capital when it becomes available. As a result, he said the company’s average-life assumptions were way too long. No wonder Allied took great pains to keep the gain-on-sale assumptions from public review. Even when Allied provided voluntary supplemental disclosure about BLX, it never revealed the gain-on-sale assumptions.

The former employee told us to look into the questionable background of Matthew McGee, the head of BLX’s top-producing office in Richmond, Virginia. In short order, we found that McGee was convicted of felony securities fraud in 1996 and spent a few months in prison. Apparently, as an employee of Signet Bank, he siphoned money from institutional customers into his family’s account. The SEC banned him from ever again working in, or affiliating with, an investment company.

His father, Robert, had been a vice president of Allied Capital in 1992 and later became a senior executive of BLC Financial. BLC Financial hired Matthew McGee after he got out of prison, while he was still serving two years of supervised release. According to the former employee, Matthew McGee sat on BLX’s credit committee. This would have violated the terms of the SBA’s waiver to BLC Financial to permit McGee’s employment after his release from prison. Moreover, the former employee told us BLX honored Matthew McGee at a recent corporate summit and held him up as an example to its other loan officers, asking, “Why can’t everybody be as productive as McGee?”

When Jesse Eisinger from

The Wall Street Journal

confronted Allied about McGee’s role, it denied McGee was on the committee. However, additional former BLX employees have also told us that McGee was, in fact, a voting member of the credit committee.

BLX had a lot to gain from pushing these substandard loans. Gain-on-sale accounting enabled the company to recognize its income at the time the loans were originated. The more loans BLX made, the more earnings it reported. Churning out loans was good for its bottom line and good for its executives’ bonuses. Not only that, but taxpayers bore most of the risk because the federal government guaranteed three-quarters of each loan against loss. This sort of arrangement can promote reckless behavior by unscrupulous operators like BLX.