Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (16 page)

The evidence that Allied changed its accounting is overwhelming. There were remarkable sudden changes to non-performing assets, PIK and fee income, and write-downs and write-ups. A few weeks later, Allied dramatically changed the narrative description of its accounting in its new 10-Q.

Allied eliminated the questionable language that echoed the white paper that first appeared in the 2001 annual report. The company replaced it with new prose describing its use and interpretation of the current-sale test based on enterprise value. The June 2002 10-Q declared for the first time, “The fair-value of our investment is based upon the enterprise value at which the portfolio company could be sold in an orderly disposition over a reasonable period of time between willing parties other than in a forced or liquidation sale. The liquidity event whereby we exit a private finance investment is generally the sale, the recapitalization or, in some cases, the initial public offering of the portfolio company.”

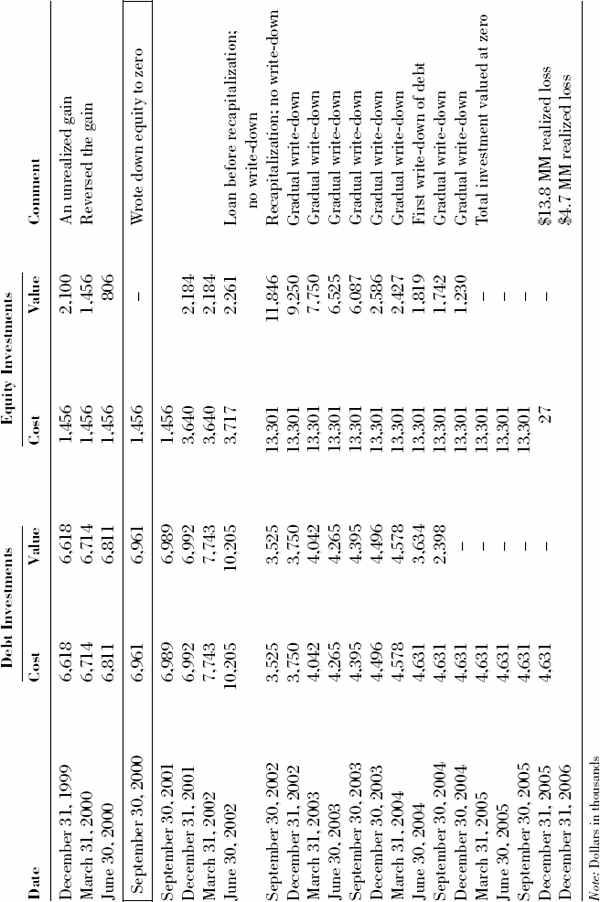

Over time, the effects of the new accounting persisted. Fees, interest, and PIK income stayed lower. The number of write-ups and write-downs recognized each quarter remained more pronounced. Earnings that had been growing steadily and predictably became volatile and unpredictable. Net investment income per share, which grew in a straight line for several years through the first quarter where they reached fifty-three cents per share, reversed their steady upward trend and became more volatile and stopped growing. They have yet to return to anywhere near that first quarter of 2002 level (see

Figure 12.1

).

Allied not only changed how it evaluated its portfolio, but also changed how it wanted investors to evaluate the company. In the past, Walton directed investors to focus on recurring net investment income (also called operating income) and observed that capital gains were nice but unpredictable. With the new accounting, Allied’s net investment income no longer approached the quarterly distribution. Instead, Allied refocused investors on taxable income, which consists of net investment income plus realized capital gains. To that end, Walton announced that the company would no longer give earnings guidance and from then on would only provide “dividend” guidance for its tax distribution.

“The dividend, as you know, is based on taxable earnings,” he said. “We find that the timing differences between tax and GAAP earnings result in our GAAP earnings being less meaningful to shareholders. . . . The reality for Allied Capital and its shareholders is taxable income supports the dividend, and although GAAP earnings are useful as a predictor of future taxable income, our primary focus is on cash distribution to shareholders, which are paid from taxable income.”

Distributions are much more predictable and manageable than earnings. Distributions are declared at the discretion of the board and limited only by the company’s ability to fund them. Taxable income is managed and maximized by selling winners and keeping losers and Allied has significant control over which investments it exits.

In May, Sweeney had said, “What we do think is important to our valuation as a public company is our net income, which communicates our earnings power to shareholders.” Now, just two months later, Allied wanted everyone to ignore that and concentrate solely on easily manipulated “taxable earnings” and its distributions.

Allied let me through to ask a question on the second-quarter earnings conference call. Perhaps my complaints that I had been screened got back to them. I questioned Allied’s new enterprise value valuation technique, and referenced

In Re Parnassus,

a case where the SEC ruled that investment companies should value the actual securities they own, as opposed to the value that could be achieved in the sale of the entire company when there were no bids pending. Sweeney gave a lengthy speech, indicating that the value of a company is linked to the value of its securities and how Allied interacts with other co-investors. She did not answer my question. Walton chimed in, pointing out that liquidity events happen when the company is sold, and that they had no plans to sell the securities.

I pointed out that the SEC current-sale test is based on the securities they actually own as opposed to the whole enterprise. I described how debt securities fall in value if the equity cushion erodes. I observed that under their standard, they would carry the debt at the same value regardless of whether it was supported by a fat equity cushion or an extremely thin one. Sweeney replied, “I think that you end up with the identical result,” and proceeded to talk about how equity values rise and fall in the same way that enterprise values rise and fall. I pressed that I was talking about debt instruments, not equity instruments. Sweeney responded by stating the obvious, saying that this is why there is equity beneath the debt, so it is the equity that suffers first.

Finally, Walton effectively ended the discussion, “David, we really have written and talked about this extensively. I would love if you wanted to give us a call to chat about it. We would be delighted to talk with you about it, but I think right now people want to learn a little bit more about our company.”

CHAPTER 13

Debates and Manipulations

Following the disappointing second-quarter earnings, Allied’s stock fell to $16.90 a share on July 24, 2002. The stock has never traded below that since. I sent a second, fifteen-page update to the SEC on July 31, 2002. I discussed Allied’s aggressive comments in its white paper and compared it to the annual report, demonstrating that Allied incorrectly followed SBA, rather than SEC accounting. I described Allied’s accounting transition to the enterprise valuation method and explained why it still was not SEC compliant. I dissected Allied’s unreasonable write-up of BLX and discussed the inflated interest rates Allied charged BLX and Hillman. I noted Allied’s false statements that its accounting was “consistent” when it was not.

To the extent the revaluations reflected changes in value that should have been made earlier, I asked the SEC to force Allied to restate results to reflect when gains and losses actually occurred and explain publicly how it changed its accounting.

I questioned whether Allied matched gains with losses to hold income steady. For example, write-downs increased from $15 million in the first quarter of 2002 to $80 million in the second quarter. Write-ups increased from $14 million to $99 million at the same time. Was this a coincidence—or had Allied either created write-ups to match the write-downs or limited the amount of write-downs to the amount of write-ups it could find? Finally, I enclosed a copy of the BancLab analysis and discussed what the former BLX employee told me without identifying him.

I figured when the SEC followed up on my letter, it would call to get his contact information. Yet, no one from the agency contacted us. I was disappointed by the lack of interest and diligence.

Allied announced it would have an investor day in early August. The event would last for several hours and give us a chance to ask questions in person. James Lin and I flew to Washington to participate. It was a noncombative meeting that covered little new ground. Allied paraded on stage a large number of senior officers demonstrating a deep, experienced team. The group appeared quite presentable.

Many people think you can spot crooks by their appearance. The stereotypical crook looks like a mobster, flaunts gaudy jewelry, or sports an all-season tan. The Allied team had none of this. They were well dressed and well spoken, sounded earnest, and seemed like nice people. In fact, they were quite charismatic.

Some of my favorite movies, including

The Sting

and

Dirty Rotten Scoundrels

, feature well-spoken, attractive, confidence men and women. Perhaps the same can be said for some of the CEOs behind real-life scandals I had experienced, including Gary Wendt (Conseco), Al Dunlap (Sunbeam), and Donal Geaney (Elan), not to mention Bernie Ebbers (WorldCom) and Ken Lay (Enron).

Instead of arguing with its critics, the company played to its core audience. It was as if Allied modified P. T. Barnum, as illustrated in Mike Shapiro’s cartoon (see

Figure 13.1

), “Remember, you can fool some of the people all of the time. Those are the people we need to concentrate on.” Allied was much more positive, even friendly. There was hardly any mention of the issues that concerned us.

However, Allied was plainly scared of uncontrolled questions and answers. Most investor days allow a lot of time for Q&A. Here, Allied budgeted only a half hour and pointedly required questions to be submitted on 3" × 5" index cards. Suzanne Sparrow, the head of Investor Relations, collected the card pile and selected softball questions to paraphrase to Walton. I filled out about four cards and signed them. Sparrow didn’t pick any of my questions.

Sparrow asked Walton whether he would sign the financials under the newly enacted Sarbanes-Oxley laws. He indicated that he would have no trouble doing so.

In for a penny, in for a pound.

In this Q&A format, Allied had nothing to worry about. Walton had such a good time pounding the fat pitches out of the park that when time expired, he looked over to Sparrow and said, “I’d be willing to take a few more.” There was a grumble from the room; people were plainly ready for lunch.

Lunch was more interesting. Robert D. Long, a managing director of Allied and one of the speakers at the event, came up to me as we were breaking to eat. He told me that we have a mutual friend, Chris Fox, over at Cramer Rosenthal McGlynn. I have known Fox since 1994. Long sat down and joined us for lunch.

In addition to Long, our table included a young, aggressive analyst from a mutual fund that held Allied shares. He was not shy in telling me that we were wrong about the company. He said that Allied was soon going to announce big news that would bury the shorts and implied that his close ties to management gave him an informational edge. Long sat next to me and also tried to convince me that our take on the company was wrong. At least he was a real gentleman about it. He conceded we made many good points in our analysis.

I asked about the sudden large number of mark-ups and mark-downs in the portfolio. He told me that Allied applied a sharper pencil. He went on to say that Allied was under a lot of heat from its regulators. Allied had told everyone that the SEC approved everything it did and our complaints were completely off base. Now I knew from the inside that Allied had not applied the valuation method consistently. And better yet, the SEC was doing something!

I pressed him on the related-party fees, interest from BLX and pointed out how circular this was. As I wrote in Chapter 11, he told me that BLX

should

be consolidated. There is a way that Allied could do that if it wanted to. His admissions were the highlights of my day. I left the meeting optimistic the system was working and Allied would get its just desserts.

Shortly after the investor day, I received a call from another professional investor. He had read our research and had wondered about Allied for years. He knew about Allied’s investment in ACME Paging.

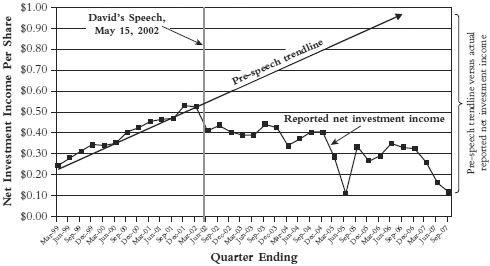

According to Allied’s SEC filings, its original investment in ACME was in place by the end of 1997. At that point, Allied thought that the equity portion of its investment called “Limited Partnership Interests” had a gain. Allied reversed the gain in the March 2000 quarter and wrote the Limited Partnership Interests to zero in the September 2000 quarter. Meanwhile, it held its debt investment at cost. Allied invested additional equity in the December 2001 quarter and increased its debt and/or equity investment each quarter through September 2002.

The investor told us what had happened. He said ACME was a troubled Brazilian paging operation. Competition from cell phones and the devaluation of the Brazilian currency hurt the company. Brazil had also experienced severe economic turmoil. ACME Paging had been shopped for sale in 2001, but there were no buyers, so the company was recapitalized.

The equity holders essentially walked away and handed Allied the keys, and, as noted, Allied increased its investment. According to its SEC filings, Allied continued to value ACME at cost. The fellow’s view that Allied deferred recognizing a loss in this investment proved out, as Allied gradually wrote-down the investment beginning in the December 2002 quarter, with further write-downs each quarter through March 2005, at which point, Allied carried ACME at zero value (see

Table 13.1

).

Table 13.1

Acme Paging