Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (18 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

In August 2002, Professor André Perold, who teaches an investment course at Harvard Business School, called to ask if I would meet with his class. He had heard about Greenlight’s work on Allied and wanted to teach the story. I checked into Perold’s reputation. It was excellent, so I agreed.

I met with his class in October, and Perold discussed Greenlight’s Allied analysis with his students. I took fifteen minutes of questions at the end. Perold’s lecture seemed supportive of our thinking. The student reaction was mixed. The class materials included the analysis we posted on our Web site, which had a discussion analogizing Allied’s relationship with BLX to Enron’s relationship with its Raptor partnership. One student thought the comparison was unfair. Others nodded in agreement.

I explained that we said that the relationships were analogous in that both were controlled, unconsolidated entities that contributed to the parents’ earnings without any transparency in the underlying results. In both cases, the parent company guaranteed the financing. In Raptor’s case this came from a pledge of Enron stock, and in BLX’s case from equity investments and debt guarantees. No one in the class seemed inclined to argue. Perold said he wanted to write a case study and would invite Allied to tell its side.

While I was in Boston, I learned that Deutsche Bank initiated research coverage of Allied with a “Sell” rating. This was surprising. Analysts rarely urge investors to sell. If they don’t like a stock, they usually mute their language, telling investors not to buy more and rate the stock “Hold.” A “Sell” rating often angers the company, its institutional investors and creates problems for the analyst.

In an extraordinary move, the New York Stock Exchange, normally a slow-moving organization, decided to immediately investigate the “Sell” recommendation and hauled in Mark Alpert, the analyst who issued the recommendation, and the Deutsche Bank institutional salesman who covered Greenlight. The salesman had sat with me at the Allied investor day, and Allied, always looking for a good conspiracy, cried foul. The Exchange questioned the salesman and the analyst about whether Greenlight had influenced the report.

We had no role in the recommendation. I only had a single, brief conversation with Alpert several months earlier. I had no idea whether he agreed with us or not and had no indication he would begin to cover Allied. The Exchange’s investigation ended without action.

As Alpert put it, “It’s ironic, especially in today’s world of research, that the NYSE would investigate a sell recommendation. What better way to intimidate independent thought? It was clear from the beginning that I had been accused of accepting compensation from short seller(s). I assume Allied was behind the allegation.”

According to Greenlight’s Deutsche Bank salesman, Allied was quite upset and wanted the “Sell” recommendation removed. At the end of the year, Allied got its wish when Alpert left and the bank ceased to cover Allied. A few months later, Allied let Deutsche Bank—which, at that point, no longer even had an analyst covering the stock and had never underwritten an offering for Allied—underwrite the first of at least five stock offerings, for which the bank made millions of dollars in fees.

CHAPTER 15

BLX Is Worth What, Exactly?

The equity and high-yield bond markets plummeted in the third quarter of 2002, following the WorldCom fraud. Allied announced its quarterly results, which were only a few cents below analysts’ estimates. Operating income actually improved, led by a pick-up in PIK income. Allied again had a large number of write-ups and write-downs during the quarter—ending in a wash. Most notably, Allied held its investment in BLX constant. It was hard to imagine how Allied justified this, since the stock prices of BLX’s three publicly traded comparable companies Allied used for valuation purposes fell an average of 32 percent during the quarter.

During the earnings conference call on October 22, 2002, Allied discussed accruing income from controlled companies. According to Sweeney, “What we don’t want to do is accrue interest income if we’re continuing to fund them on a routine basis because we look at that as if we are accelerating interest income that we are funding. So we don’t do that.” On that basis, how could they recognize income from BLX? Allied’s SEC filings revealed BLX burned cash and needed ongoing capital for its operations. Allied routinely contributed that capital, either directly through fresh investment or indirectly by guaranteeing bank loans.

At the end of the conference call, Walton gave tax distribution guidance. The company estimated distributions of $2.20 a share in 2002, followed by 5 percent growth in 2003. The company’s previous target had been a 10 percent annual increase. Management explained on the conference call that 10 percent had been more of a long-term goal. The company further said net investment income would be 80 percent of the 2002 distribution and 85 percent of the 2003 distribution. This implied net investment income in 2003 of $1.95 a share. When the dust settled on 2003, net investment income was only $1.65. Allied filled in the gap with additional capital gains. By then, Allied managed to convince its shareholders money was money and the distribution was the distribution no matter how it was funded. In fact, Allied came to argue that net capital gains are actually better than net investment income because they are taxed to the investor at a lower rate. In May, Walton had pushed the opposite (more conventional) view: Net investment income is superior to capital gains because it is more predictable.

Allied defended its treatment of BLX with additional misleading comments. When questioned about the $100 million of residuals on BLX’s balance sheet at the Bank of America investor conference in September 2002, Sweeney told the audience, “I’d buy a $400 million stream of cash flows for $100 million.” This answer created the misimpression that BLX’s residuals had hidden value. However, embedded in the $400 million figure was the absurd assumption that no loan ever defaulted or prepaid. Allied had no interest in allowing investors to judge the value for themselves by sharing the actual prepayment and default assumptions or history. Further, Sweeney told investors at a Piper Jaffray conference in November 2002 that BLX’s SBA loans “perform in line with the national average.”

I provided reporters from both

The New York Times

and

The Wall Street Journal

with the BancLab analysis, access to the former BLX executive who had contacted us, and described Allied’s inflated valuation of BLX. I knew Jesse Eisinger from the

Journal

had visited Allied. As time passed without an article—his initial period for an exclusive had long since passed—I came to believe there wouldn’t be one, so I decided to write the story myself. Several months earlier,

TheStreet.com

, a financial news Web site, invited me to become a contributor. I took them up on the offer and wrote a two-part article titled, “The Joker in Allied Capital’s House of Cards,” which the site published on December 10 and 11, 2002. The story highlighted the problems with gain-on-sale accounting, BLX’s loan performance, questioned the nonconsolidation of BLX and recounted the absurdity of Allied’s BLX valuation. At the same time, we added the BancLab analysis to our Web site.

There was no measurable reaction to the story anywhere. None of the brokerage firm analysts commented on any aspect of the issue. When the stock, which traded at about $22 per share at the time, did not react, Allied’s management probably thought no immediate response was necessary. On the conference call discussing fourth-quarter results held two months later, Roll responded, “We are aware of what we believe to be an inaccurate report in the market regarding BLX and its 7(a) loan portfolio quality.” Again, she didn’t specify any inaccuracies, but said that according to BLX’s own data, the losses on the unguaranteed pieces over the last five years averaged less than 1 percent and the performance was better than the national average.

Roughly two years later, I learned the difference between the BancLab data, which showed defaults, and Allied’s description of “losses.” When loans become 60 days late, the SBA considers it a default. BLX notifies the SBA and requests the SBA to satisfy the guarantee, which the SBA pays. BLX continues to try to collect and/or resolve the default for as long as it can, which can be years. Neither BLX nor the SBA count the loan as a “loss” until the loan resolution is complete. So BLX’s “losses” are “small” mostly because it doesn’t resolve defaulted loans in a timely fashion.

However, a benefit of publicly discussing Allied was hearing from others. Jim Brickman, a retired real estate developer from Dallas, introduced himself by e-mail. Someone had pointed him to Greenlight’s analysis because of his background in SBA lending. Brickman served on a creditor’s committee responsible for liquidating and evaluating the value of the SBA platform of Amresco, a Dallas-based lender that went bankrupt in 2001. With the assistance of Houlihan Lokey, a boutique investment banker, he sought to find a buyer. There was none at even a fraction of book value. So Brickman approached the BLX discussion with a clear understanding that SBA lending platforms are not worth sixty-five times earnings or five times book value, especially when the balance sheet has multiples of its book value in residual assets.

Recall that residuals are the estimated present value of future cash flows. The estimate depends on various assumptions. Historically, many companies have used assumptions that proved too optimistic, leading to future write-downs. As a result, investors take a skeptical view of residual asset values. Allied’s staunch refusal to provide the assumptions BLX used to estimate its residuals raised further doubts.

Brickman’s e-mail began a long dialogue. While I’ve spent more time on Allied than I can quantify, Brickman has spent much more; he is retired and his kids have grown. As he sees it, “These people believe they are above the law.” He has become an expert at searching public records, analyzing information, and has been a major collaborator in identifying problems at Allied and BLX. He is one of the best forensic detectives I have ever met. He finds the Allied story—how it has developed and persisted—as amazing, surprising and disheartening as I do.

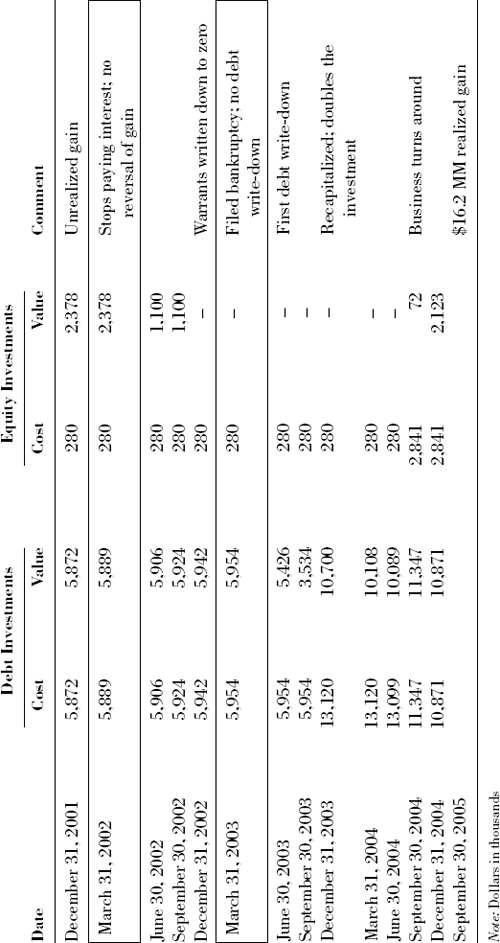

His first big find involved two of Allied’s investments, GAC and Fairchild Industries, each of which filed for bankruptcy in early 2003. The bankruptcy documents indicated that Fairchild defaulted on $6 million of senior debt to Provident Bank in 2001 and stopped paying interest on Allied’s junior debt investment in January 2002. Despite this, Allied valued its debt investment in Fairchild at cost throughout 2002 and even carried its warrants at an unrealized gain. In December 2002, Allied wrote its warrants to zero. Even after Fairchild went bankrupt, Allied carried its loan at cost in March 2003. Finally, Allied began to write-down the loan in June 2003 (see

Table 15.1

). Ultimately, after Allied doubled its investment, Fairchild’s results improved and Allied exited with a gain in 2005.

Table 15.1

Fairchild Industries

Brickman’s work on GAC showed that it was another case of Allied ignoring reality. Remember that Sweeney taunted the short sellers about not doing their basic homework on GAC. Though it was Allied’s third largest investment at cost, Allied didn’t feel a need to disclose its bankruptcy via press release, in its earnings announcement or even in its 10-Q. Allied appeared to announce only good news. For example, around the time of GAC’s bankruptcy, Allied issued separate press releases announcing a $7 million gain on the disposition of CyberRep and an $8.4 million gain from selling Morton Grove Pharmaceuticals.

Bankruptcy documents showed that GAC had only $6 million of revenues and negative cash flow. Given what

Off Wall Street

reported about GAC, it is doubtful the business was ever profitable. Even as Sweeney had said the critics didn’t know what they were talking about, Allied wrote GAC down $5 million in June, $9 million in September, and $5 million in December 2002, leaving the value at $20 million. This was a good example of Allied taking gradual write-downs to smooth its results. Walton was asked about GAC on the first-quarter conference call. Without even acknowledging the bankruptcy, he indicated there had been management changes and he thought there was “an interesting business plan going forward.” We never learned just how interesting that business plan must have been.

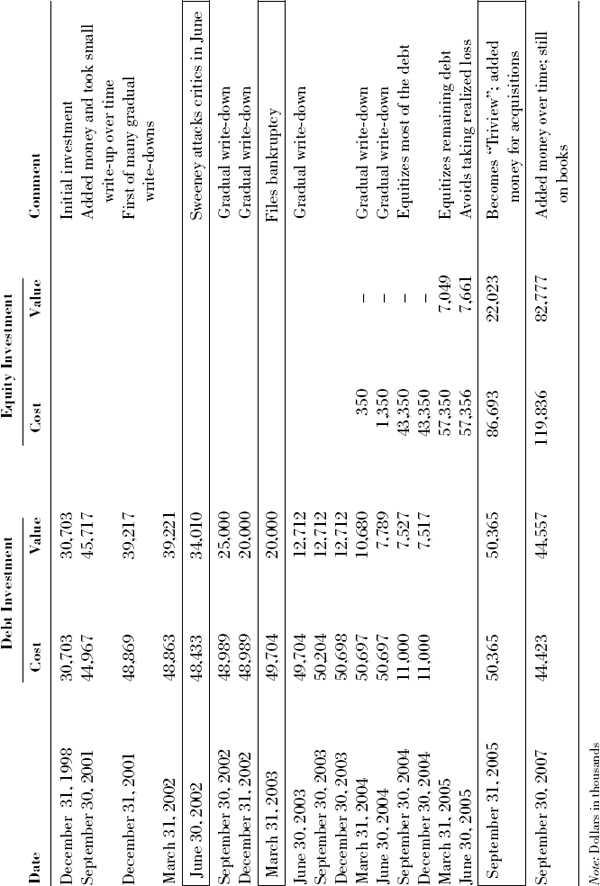

The bankruptcy forecast indicated that GAC expected further declines in performance. Over time, the actual results came in worse than the forecast. By June 2005, Allied showed an unrealized loss of $50 million on its original $50 million investment. It had invested an additional $8 million during the bankruptcy, which it carried at $8 million. As part of its strategy of selling the winners and keeping the losers, Allied elected not to take a $50 million realized loss, which would have provided a valuable tax shield for shareholders—but would have reduced Allied’s taxable income, which supports the distribution. Instead, Allied changed the name of the company to Triview Investments Inc. and infused another $78 million to make acquisitions in an unrelated field, taking an additional $15 million write-down. This was an example of Allied’s sacrificing economics for improved optics (see

Table 15.2

).

Table 15.2

Galaxy American Communications

Allied also had an investment in, and had a representative on the board of, Redox Brands, a consumer cleaning-products company. Todd Wichmann, a former CEO of Redox, called in early 2003 to tell us Redox violated its bank covenants and obtained a waiver and an additional investment from Allied in the second quarter of 2002. Though Allied added $7 million to protect a $10 million investment under duress, it did not write-down the initial investment. The very next quarter, Redox appeared likely to violate the revised covenants. Wichmann told us that

Allied put pressure on management to falsify the financial statements to hide the default from the bank

. Wichmann said management refused to go along, but carefully documented Allied’s inappropriate request.