Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (15 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

CHAPTER 12

Me or Your Lyin’ Eyes?

A few days later, on July 23, 2002, Allied announced its second-quarter earnings. We’ve seen a lot of examples in short sales where the company maintains that the short-sellers are wrong, but at the same time the company has to change either its accounting or business practices so that the results fail to live up to previous standards. This process began for Allied with this quarterly announcement.

Allied announced only forty-one cents per share of net investment income (this term excludes write-ups and write-downs of investments and is used interchangeably with operating earnings) compared to fifty-three cents per share the prior quarter and forty-six cents in the year-ago quarter. Analysts expected fifty-seven cents per share. Weeks before, Walton highlighted the importance of these “recurring earnings” from interest, fee, and dividend streams that excluded volatile gains and losses in the portfolio. Interest income was less than expected, because non-accrual loans more than doubled from $40 million in the March quarter to $89 million in the June quarter. PIK (payment-in-kind) income fell from $13 million in the first quarter to $8 million in the second quarter, and fee income fell from $16 million to $11 million.

Clearly, Allied adopted a more conservative revenue recognition policy. Because Allied recognized PIK income in a wide number of loans, there was no other explanation for the 40 percent sequential decline. Allied probably took a new, more conservative view of non-accruals, interest income and fees that caused the sudden shortfall. Allied also changed how it wrote-up and wrote-down investments. In previous periods, Allied made few adjustments to the investment values, but now adjusted a large number of investments. Allied wrote-down the “money good” investment in Startec’s operating company from $10.2 million to zero and did the same to the remaining $4.3 million investment in Velocita.

Allied took $67 million in other write-downs. According to Sweeney, Allied wrote-down five companies by $20.6 million due to softening in the manufacturing sector, five other companies affected by declines in technology spending by $14.7 million, two media companies by $7.7 million due to declining values in the sector, and, finally, two others suffering “difficulties, as a result of the attacks on September 11,” by $11.3 million. Allied didn’t explain why it took over nine months to recognize September 11 impacts. It was plain that all these bad things did not happen in a single quarter, but reflected Allied’s response to scrutiny.

Allied also found a large number of offsetting write-ups. In fact, the headline earnings were 71 cents per share, which exceeded analysts’ forecasts. The commercial mortgage backed securities (CMBS) portfolio, which Allied historically valued at amortized cost, was now worth $20.7 million more because, Sweeney said, “in accordance with ASR 118, we determined the fair-value of the portfolio on an effective yield-to-maturity basis.” Tellingly, Allied still contended the mezzanine loan portfolio shouldn’t be valued on a yield-to-maturity basis, as per ASR 118.

During the earnings conference call Q&A, Don Destino, a bullish analyst from Bank of America, observed that this was the first time Allied meaningfully changed the valuation on the CMBS portfolio and asked whether it planned on doing the same exercise from now on. “Yeah, well, Don, actually, we do this every quarter,” Sweeney replied. Sure.

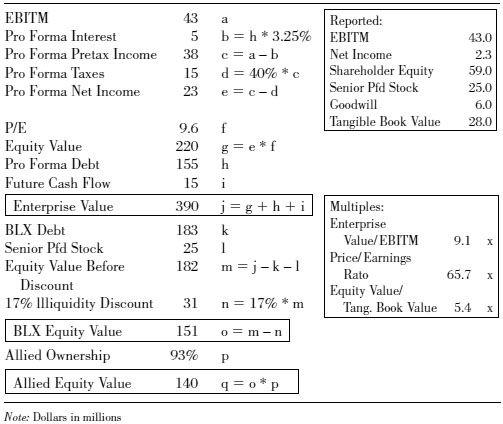

Even more problematic, Allied increased the value of Business Loan Express by $19.9 million and provided one of the most convoluted explanations I’ve ever heard. When Benjamin Disraeli said, “There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics,” he could have used this as a case study. Penni Roll, Allied’s CFO, said that in 2002 BLX had $85 million of revenue, $43 million of earnings before interest, taxes, and management fees (EBITM), $4 million of pretax profits, $286 million of total assets, and total debt of $183 million. Roll said financial service companies are valued using net income.

The problem was, with all the fees and interest Allied charged BLX, it had minimal net income. “So to value BLX,” Roll explained, “we determined what this company’s net income would be with a capital structure that would likely be imposed upon this company by a buyer if it were sold today.” Allied already owned BLX and could impose any capital structure it liked on BLX. Why would a different owner use a better capital structure, if there were such a thing?

“As you know, we have capitalized BLX with $87 million in subordinated debt in addition to our preferred and common equity investments,” she continued. “For purposes of valuation, we assumed that our subordinated debt would be treated as equity and that BLX would be able to increase the size of its senior debt facility.”

How could this be? BLX, with Allied owning it, had a much smaller senior lending facility. That facility could only be obtained with Allied guaranteeing the first 50 percent of any loss the lender would have. Why would a different owner be able to obtain a larger senior facility on better terms?

The analysis continued. “We believe that BLX could have by the end of 2002 borrowed senior debt of approximately $155 million secured by assets on their balance sheet[, since]. . . at any point in time roughly 30 to 40 percent of their assets are in cash or government-guaranteed interests.”

How did they come up with $155 million? Thirty-five percent of $277 million in assets was about $95 million, roughly what BLX had drawn on its line. What was the rest of the collateral? (Incidentally, though Roll said BLX had $286 million in assets a few moments earlier on the conference call, Allied’s 10-Q indicated BLX had only $277 million in assets at the time.)

Roll continued, “We included an annual interest cost of $5 million and subtracted that from their approximate $43 million of EBITM to arrive at a pro forma profit before tax of about $38 million.” This implied a 3.25 percent interest rate on $155 million of debt. This is approximately the rate Allied charged just to

guarantee

BLX’s existing bank debt, which BLX paid in addition to what they paid the senior lender. How could the hypothetical larger bank facility also come at a reduced rate? Allied, a much better credit, paid about 7 percent on its own debt. If BLX could really borrow $155 million at 3.25 percent, it should have done that.

“We exclude management fees paid to Allied Capital in the pro forma calculation because the majority of our integration services have been completed and a new buyer for BLX would not need to incur these expenses going forward,” Roll said. How could they exclude the management fees? Weeks earlier, Allied explained it provided essential, value-added, and easily justifiable services to BLX for the fees. It was suspicious that now that Allied was under scrutiny, suddenly BLX wouldn’t need to purchase as many services from Allied.

Next, Allied explained that it took the $38 million of pro forma pretax profit, taxed it and applied a price-to-earnings (P/E) multiple. It calculated the multiple through several methods, including looking at the trading multiples of comparable companies. Allied selected CIT, Financial Federal and DVI as comparables. However, CIT and DVI traded around book value. When the market values companies based on book value rather than earnings, the earnings multiples lose relevance. Further, CIT and Financial Federal employed portfolio-lending accounting, where income is recognized over the life of the loan, instead of gain-on-sale accounting, where income is recognized up-front at origination. The market generally rewards more conservative accounting with a higher multiple. Here, Allied imputed the relatively higher multiples of the portfolio lenders to BLX’s lower-quality gain-on-sale-driven results.

Allied completed the valuation of BLX by adding back the $155 million of hypothetical senior debt and adding $15 million of future cash flow to calculate BLX’s enterprise value to be $390 million. When all was said and done, Allied applied a 17 percent discount to account for sale costs in the current environment and determined that the value of BLX, miraculously increased by $20 million.

The implication of this tortured exercise was that Allied determined BLX was worth nine times EBITM,

sixty-five times net income

and about

five times book value

. Sixty-five times net income and five times book value do not pass the laugh test: No one would value a gain-on-sale securitizer that richly. Market values for gain-on-sale securitizers fell so low that once DVI went bankrupt a few months later, we could no longer identify a publicly traded company that generated a large portion of its income through gain-on-sale securitizations.

Table 12.1

Allied’s June 2002 Valuation of BLX

Later in the call, Darius Brawn of Endicott Partners again raised the issue of how much of BLX’s $85 million in revenue came from gain-on-sale. Sweeney indicated that she didn’t know off the top of her head, but after Brawn pressed her, Sweeney said that the cash portion of BLX’s revenues was around 50 percent to 70 percent. This meant that the 30 percent to 50 percent of $85 million in revenues, or $25 million to $42 million, was non-cash. Since gain-on-sale revenue generally flows through the income statement without marginal expense, this meant the majority of the $43 million of EBITM was non-cash.

For the first time, Allied provided some summary financial information for BLX in its 10-Q filed weeks later. Since the last available disclosure about BLX at its formation in December 2000, BLX’s debt increased $65 million to $183 million and an intangible asset created by gain-on-sale accounting called “residual interests” roughly doubled to $106 million. As the residual interests were almost four times the tangible equity, you could call the valuation whimsical, or imaginative, or fanciful—but not supportable.

Putting it all together, BLX was a problem in three ways. First, BLX made loans improperly. Second, BLX used aggressive accounting techniques to inflate its results. Finally, Allied’s valuation of BLX had no reasonable basis, even if BLX’s business and accounting results had been genuine. Frankly, as we were learning more about BLX, we were coming to believe Allied’s investment could really be worthless.

Allied sought to convince investors it wasn’t a fraud by giving evidence that it didn’t behave like other frauds. Allied paid distributions, proving the cash wasn’t missing. Insiders purchased shares, signaling the market that nothing was amiss. It had consistent accounting, validating its four decades of success.

It was like the old Richard Pryor joke: “What do you do if your wife walks into your bedroom and finds you in bed with another woman? Deny! Deny! Deny! Who are you going to believe? Me or your lyin’ eyes?” So, too, with Allied.

Despite the large changes in Allied’s accounting practices, to maintain the confidence of inattentive or unsophisticated investors, management repeatedly advanced the illusion that Allied’s accounting was consistent. During the second quarter of 2002 earnings conference call, Walton led off his discussion of valuation, “as a result of our

consistent

process of determining the fair-value of our portfolio in good faith . . .” Moments later, Sweeney echoed, “As we stated in our public filings, we used a

consistent

methodology to value our portfolio companies in keeping with the guidance provided by the SEC and industry practices.” Before turning to the Q&A, Walton reiterated, “Let me emphatically state that we will continue to apply a

consistent

and prudent valuation methodology that is in accordance with all regulatory guidelines as we have always done.”