Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (42 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Jim Carruthers put it best: “If the SEC had come in 2002 and promptly made these findings and the SBA acted on the fraud when we told them right away, Allied stock would have gone to $3.” Instead, the shares closed at $31.84 the day of the SEC order. I would add that Allied management wouldn’t be in place today and may have served time in jail.

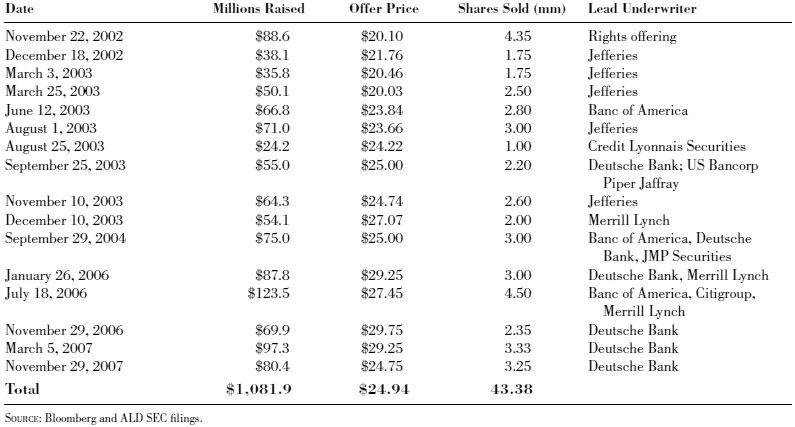

Instead, it took the SEC more than two years after my speech to begin investigating Allied and nearly another three years to complete its inquiry. The findings seemed stale because it took the SEC so long to act. During those five years, the economy nicely recovered from its recession and Allied raised about $1 billion of fresh equity in sixteen offerings (see

Table 31.1

). This was raised from thousands of retail and institutional investors under pretense that Allied followed the rules and was simply the victim of a “short attack.” These are the investors the SEC is supposed to protect.

Table 31.1

Equity Offerings by Allied Capital since January 2002

So now it was cash-out time: The very afternoon of the SEC order, Allied began the long-delayed “stock ownership initiative” by making a tender offer for 16.7 million vested insider stock options. One would have thought it would have waited a day or two, maybe a week, just to keep from blushing.

CHAPTER 32

A Garden of Weeds

The SEC and other believers took comfort that with third-party valuation assistance, Allied would properly value its investments. I didn’t. As discussed before, Allied did not hire the consultants to perform appraisals. How valuable could these “negative assurances” be coming from third parties that signed-off on the BLX valuation for years? I was certain this fix was form over function: Allied’s underlying ethos was unchanged.

Over the years we have learned that even though Allied’s senior management is dishonest, it did not mean Allied could not and did not make some good investments. There may have been some winners still remaining in the portfolio. However, Allied’s practice of harvesting the winners and keeping its losers had left it with poor prospects. According to Allied’s own valuations, the portfolio had more unrealized depreciation than unrealized appreciation—and that was before taking into full account BLX’s meltdown.

The 10-Q for the second quarter of 2007 included a new disclosure about the BLX investigations. “In addition, the Office of the Inspector General of the U.S. Department of Agriculture is conducting an investigation of BLX’s lending practices under the Business and Industry Loan (B&I) program.” Again, this disclosure appeared as part of a general discussion of BLX rather than under “Legal Proceedings” and Allied indicated it was “ongoing,” misleading the casual reader to believe that the USDA investigation was not a new development. Allied did not disclose when this investigation began and made no mention of it in the earnings release or conference call the prior day.

Later in the 10-Q, Allied warned, “Due to the changes in BLX’s operations, the status of its current financing facilities and the effect of BLX’s current regulatory issues, ongoing investigations and litigation, the Company is in the process of working with BLX with respect to various potential strategic alternatives including, but not limited to, recapitalization, restructuring, joint venture or sale or divestiture of BLX or some or all of its assets. The ultimate resolution of these matters could have a material adverse impact on BLX’s financial condition, and, as a result, our financial results could be negatively affected.”

Moreover, the 10-Q also disclosed that BLX was in default under its credit agreements and had received temporary waivers from its lenders. Even so, Allied advanced BLX another $10 million and BLX drew down on its bank line (the first losses up to half the line were guaranteed by Allied) a further $50 million. The 10-Q explained, “BLX’s agreement with the SBA has reduced BLX’s liquidity due to the working capital required to comply with the agreement.” Allied did not explain why, in light of these troubling facts, it did not take a large, immediate write-down. Instead, Allied wrote BLX down by merely $19 million in the quarter. Inexplicably, Allied continued to value its stake at $220 million, implying an enterprise value in excess of $550 million counting BLX’s borrowings under its credit facility.

In June 2007, Allied announced it raised $125 million for the newly formed Allied Capital Senior Debt Fund, LP, a levered fund Allied managed where it would receive management and incentive fees. Allied committed 25 percent of the capital and raised the balance from outside investors. As part of the fund formation, Allied shifted $183 million of loans off its balance sheet to the new fund. Allied did not disclose which assets it transferred.

One of the assets that disappeared from Allied’s balance sheet that quarter was a $35 million loan to Air Medical Group, an operator of medical helicopters under the name Air Evac Lifeteam. On May 25, 2007,

The New York Times

reported that the FBI seized documents from its corporate headquarters “as part of an inquiry concerning billing and health care compliance related matters.” This followed a front-page article in the

Times

from 2005 that reported how Air Evac Lifeteam apparently sent out helicopters and charged insurers in instances that did not appear to be emergencies. Though it was a small investment, Allied increased its unrealized gain in Air Medical Group right after the FBI raided Air Medical Group’s headquarters.

On September 4, 2007, Sweet Traditions, a Krispy Kreme franchisee in Illinois, Indiana, and Missouri, filed for bankruptcy. In August 2006, Allied led a recapitalization of the then already ailing company. The bankruptcy documents indicated Sweet Traditions generated no operating profit and paid only about $275,000 to Allied in the year before the filing, about a tenth of the stated annual interest on the loan. According to Allied’s SEC documents, filed just weeks before the bankruptcy, Allied recognized $1.7 million of interest in 2006 and over $1 million in the March 2007 quarter before putting Sweet Traditions on non-accrual in the June 2007 quarter, while also continuing to value its entire $37 million investment in the debt and equity at cost.

Déjà vu.

Allied announced its third-quarter 2007 results on November 7, 2007. For the first time in years it reported a loss of sixty-two cents per share. Following a multi-year boom in lending, risky bonds and loans had declined in value across the board. On the previous quarter’s conference call, management had downplayed the impact that the market decline would have on its $4 billion portfolio, but described the turn in the credit cycle as a positive development because Allied could make future loans at improved yields. As the credit crisis spread, however, valuation multiples contracted and Allied took write-downs “particularly in the financial services sector or from portfolio company circumstances that are not significant business model issues,” according to Walton. Having harvested most of its winning investments, Allied did not have offsetting write-ups this time.

Net investment income was also poor at only twelve cents per share, after a nine-cent-per-share cost from the tender offer for insider options, which had been completed in July at $31.75 per share. Income taxes that Allied paid the government for the privilege of deferring tax distributions an additional year cost seven cents per share. Allied closed its sale of Mercury Air, and, in a blast from the past, finally recognized a realized loss in its investment in Startec Global Communications.

Walton led off the quarterly conference call by describing the results as “mixed.” Then came the surprise: BLX will “significantly de-emphasize government-guaranteed lending going forward.” BLX’s cost structure and capital requirements had become “sub-optimal.” BLX would focus on non-government guaranteed “conventional” small business lending. The result would be a 30 percent short-term reduction in originations and a write-down of BLX’s residual interests and book value leading to an additional $84 million write-down of Allied’s investment, which contributed to the loss in the quarter.

Walton continued, “To effect this change in strategy, Bob Tannenhauser, BLX’s current CEO, will take on the role of Chairman for an interim period, and John Scheurer, who has successfully built two commercial mortgage loan investment businesses for Allied Capital, will step into the role of interim CEO.” I immediately wondered whether Allied was concerned Tannenhauser might be indicted and wanted to be able to call him a “former employee” if that inconvenience came to pass.

No matter how ugly BLX appeared, Allied just kept applying rouge. To give up would cause not just a write-down, but also a realized loss. A realized loss the size of BLX would count against Allied’s kitty of undistributed tax distributions that Allied stored to give investors “visibility” into future “dividends.” Instead, Allied decided to re-focus BLX. “We believe that there is significant opportunities [sic] to build and grow BLX as a conventional small business and commercial real estate lender. John is actively working to add commercial mortgage industry veterans to expand BLX’s commercial real estate platform. We think John is the right guy to lead BLX through this change in strategy and we have the record and resources to support the company through this transition,” Walton explained. If it made sense to have Scheurer create a new commercial mortgage-lending platform, it would certainly be easier to build one from scratch, rather than on top of BLX’s mess—high cost of capital, and all.

In the Q&A session, the sell-side analysts were already trying to figure out how to spin the lousy result. Henry Coffey of Ferris, Baker & Watts offered, “If we were to throw GAAP out the window, which is something I would be happy to sponsor, Joan, what—would it be fair to, when we’re looking at your operating earnings, to exclude the excise tax as well as some of the stock option expense and then what about the IPA [Individual Performance Award] charge?”

Even with the write-downs, it remained clear that Allied had not fully reflected the changed market conditions in its valuations. On the conference call, management acknowledged that credit spreads had widened. As they failed to do in 2002, Allied did not revalue its entire debt portfolio to take into account the deteriorating market conditions. The write-downs Allied took were concentrated in its equity positions; the debt investments generally remained at cost.

Déjà vu, again.

Even after the Sweet Traditions bankruptcy, Allied still valued its non-accruing loan at cost—although this quarter it wrote-down its equity investment. Through its investment in the Callidus Capital Corporation, an asset management company, Allied had invested in a series of structured finance products, including the equity pieces of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). The market values of structured finance vehicles had fallen especially hard in the developing crisis. However, Allied wrote-down the value of its $188 million of CLOs by only 6 percent.

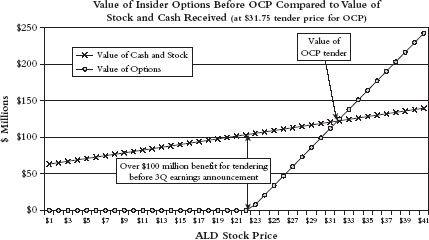

Allied shares, which stood at $31.75 in June when the company priced the tender offer for the insider options, had weakened coming into the third-quarter announcement. In response to the bad news, the shares fell sharply to a low of $21.55 on November 8, 2007. Insiders had just received $53 million in cash and 1.7 million shares of stock in exchange for 10.3 million options with a weighted average exercise price of $21.50. Had Allied delayed the option tender until the company announced this bad news, the insider options would have had little value left. This “extra” $106 million for insiders equated to about three-quarters of a year’s worth of Allied’s net investment income (see

Figure 32.1

).