Fooling Some of the People All of the Time, a Long Short (And Now Complete) Story, Updated With New Epilogue (43 page)

Authors: David Einhorn

Tags: #General, #Investments & Securities, #Business & Economics

Just like when the magician’s lovely lady assistant—having been sawed in half, smiles and moves her feet and hands to show all is well—the Allied insiders repeated their familiar sideshow pantomime: They showed their “confidence” in the stock through nominal open market purchases.

The lady had, in fact, not been sawed in half!

Walton, who had just received $14.5 million in cash (in addition to $14.5 million in stock) in the option tender, was the biggest “inside” purchaser by far, acquiring 50,000 shares for $1.1 million. The purchases received substantial media attention, including positive coverage from

Bloomberg, Barron’s, The Motley Fool

and

Insiderscore.com

. Within a couple of weeks the shares recovered to $25.47; Allied promptly sold a fresh 3.25 million shares in an overnight stock offering led by Deutsche Bank.

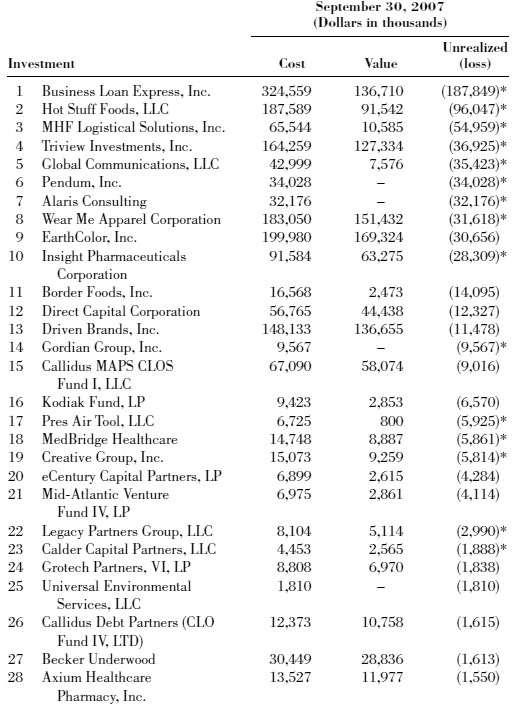

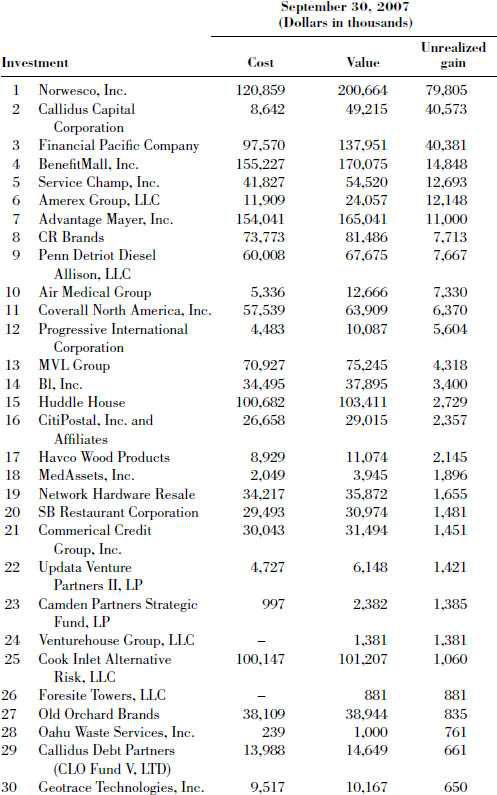

On September 30, 2007, Allied rated $3.93 billion of its $4.33 billion portfolio Grade 1 (capital gain expected) or Grade 2 (performing to plan). Allied classified only $401 million, or 9 percent, of its investments in Grades 3 through 5. Yet, as

Table 32.1

shows, $1.35 billion, or 31 percent, of Allied’s portfolio were investments that had been performing below plan in that they had either been partially written down or were non-accruing.

Table 32.1

Written-down and/or Non-Accrual Investments

Allied classified several hundred million dollars of investments that had partial markdowns to be Grade 1 or Grade 2. How could investments in such a state be considered Grade 1 or Grade 2? Grade inflation. It appeared that if Allied considered a gain likely on its equity kicker, it classified the entire investment—loan and equity—as Grade 1. The converse was not true: If Allied expected the junior portion of an investment to generate a loss, it did not downgrade the entire investment, but only the impaired junior portion.

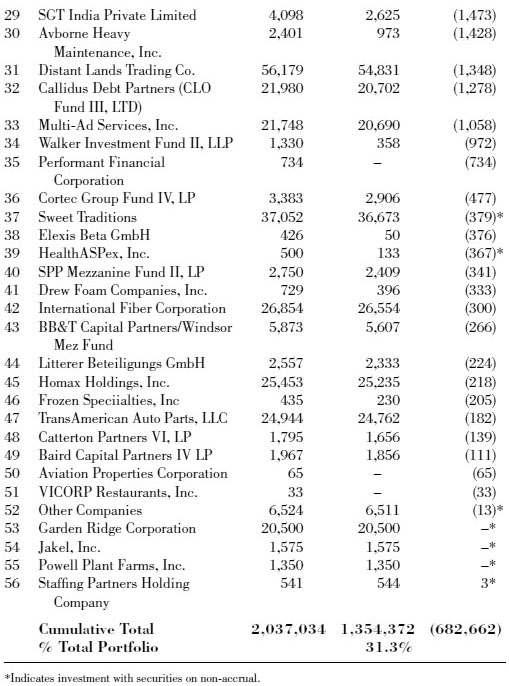

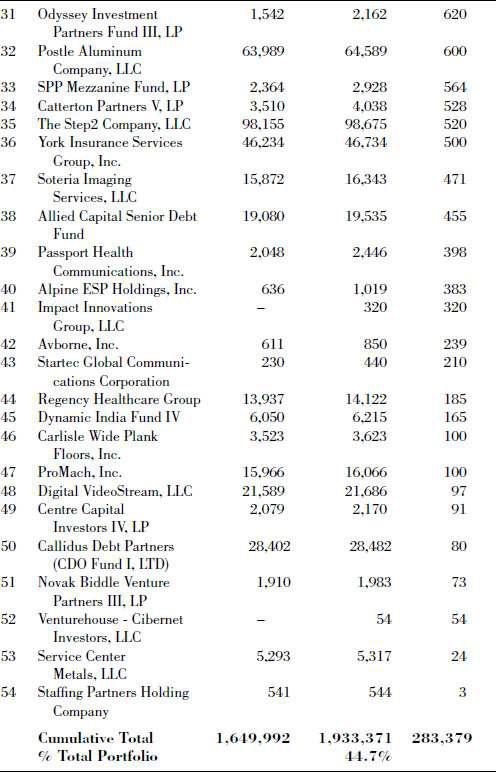

Some of Allied’s few remaining appreciated investments appeared questionable. As noted, with the sale of Mercury Air, Allied picked the last obvious flower in its portfolio. One of the largest unrealized gains left was Financial Pacific Company, a lessor of equipment to small businesses, which Allied bought in June 2004. Unlike most of Allied’s investments, there was abundant public data about Financial Pacific because it had filed documents with the SEC in anticipation of going public. Allied purchased it at a high price and a sizable premium to the anticipated public offering price. Allied paid $94 million—either three and a half times or five times Financial Pacific’s equity, depending on whether Financial Pacific retired its subordinated debt in the transaction. According to its SEC filing, the yield on the equipment leases was fixed, but Financial Pacific’s borrowings had variable rates. As a result, the filing warned that increases in short-term interest rates would have an adverse impact on the company. Almost immediately after Allied purchased the company, the Federal Reserve began a campaign of short-term interest rate increases. From July 2004 to August 2006 the Federal Reserve raised the overnight rate seventeen times from 1 percent to 5.25 percent. Despite Allied’s high initial purchase price and an interest rate headwind that had only recently begun to abate, as of September 30, 2007, Allied valued Financial Pacific at a sizable premium.

Callidus was another remaining unrealized gain. Allied bought a majority stake in Callidus (with Callidus management retaining a minority stake) in November 2003, concurrently committing to take large positions in the riskiest portions of Callidus’ future deals. Allied did not consolidate Callidus, because it considered Callidus to be a “portfolio company.” As we learned in our research about Allied’s accounting treatment of BLX, investment companies could consolidate their financials with other investment companies. On that basis, Callidus would be eligible for consolidation. The non-consolidation of Callidus enabled Allied to boost its earnings by recognizing unrealized appreciation on its investment in Callidus. If Allied consolidated Callidus, it could not book such gains (see

Table 33.2

).

Table 32.2

Written-up Investments

Allied now had limited ability to produce net investment income to sustain the distributions. Dramatically reducing Allied’s generation of recurring earnings were: lower portfolio interest yields, which had fallen from 14.3 percent in March 2002 to 11.9 percent in September 2007; reduced ability to recognize fees from controlled companies; and higher operating expenses, especially compensation. Net investment income, which almost covered the tax distribution in 2001, covered less than 30 percent of it in the first nine months of 2007. As a result, Allied adopted a capital gains strategy, fully dependent on selling winners and keeping losers.

Though Allied would do everything it could to avoid turning its unrealized losses into realized losses—especially at BLX given its slippery footing, the outcome might be beyond Allied’s control. In addition to its $190 million unrealized loss and $136 million remaining investment in BLX, Allied had a large exposure to the guarantees it made on BLX’s bank line. In September 2007, Allied agreed to increase its guarantee from 50 to 60 percent to enable BLX to obtain short-term waivers of its defaults until January 2008. In January 2008, it increased the guaranty on BLX’s bank line to 100 percent or $442 million. Should BLX implode and Allied make good on the guarantee, Allied’s realized loss could exceed $700 million, assuming that the government did not extract further restitution or penalties from Allied.

Allied had built up a large “kitty” of undistributed taxable earnings by selling its winners and keeping its losers. Allied assured its investors that this gave the company the long-term ability to make quarterly tax distributions. I believed it had become harder for Allied to find meaningful winners to harvest and the eventual losses from BLX would deplete, if not exceed, the kitty. Looking at Allied’s September 2007 valuations—without assuming additional losses at BLX, or for that matter other impacts from Allied’s aggressive accounting—Allied’s portfolio had $683 million of unrealized losses and only $283 million of unrealized gains.

All told, Allied had to distribute about $410 million per year to maintain the distribution. As of September 2007 it had about $400 million in the kitty and generated about $110 million in annual net investment income, but had $400 million in unrealized losses in excess of unrealized gains and a large additional loss likely coming at BLX. The kitty appeared under pressure.

If the kitty disappeared, Allied would be left with the option of paying the distributions out of capital as opposed to profits. But Allied’s shareholders might not notice the distinction. Cutting the distribution would be unthinkable. Allied’s focus on easy-to-manipulate taxable earnings accumulated in prior years, rather than current-year reported earnings, should have been a red flag. Paying distributions out of capital, while simultaneously raising fresh capital, fits the classic description of a Ponzi scheme. Is a Ponzi scheme a victimless crime before it collapses?

A Ponzi scheme can exist in what economists call “stable disequilibrium.” Though it is not

permanently

sustainable, it doesn’t have to fail in any given time frame. Yes, Allied has proven that it can last for years, by chronically selling fresh shares to raise more capital. Such persistence disproves nothing.

CHAPTER 33

A Conviction, a Hearing, and a Dismissal

The Justice Department began to ring up convictions from its Michigan investigation of BLX. In October 2007, Patrick Harrington, the head of BLX’s Detroit office, pled guilty to conspiracy and making a false statement to a grand jury. Noting the investigation was ongoing, Assistant U.S. Attorney Stephen Robinson told

Bloomberg

, “I anticipate there will be additional indictments.”

Harrington declined to cooperate with the investigation.

Bloomberg

reported that his attorney said, “The government always wants to go higher, but he never told anyone about it.” As of this writing, Harrington awaited sentencing. More than a dozen other minor participants in BLX-issued fraud loans pled guilty to various crimes.

According to BLX’s statement, Harrington admitted to $6.5 million in fraudulent loans in his plea agreement. BLX vowed, “All losses attributable to Mr. Harrington’s admitted criminal conduct will be borne entirely by BLX.” Notably, BLX did not promise to reimburse all the allegedly fraudulent loans it had

originated

.

Shortly after Harrington’s guilty plea, the SBA Office of Inspector General posted the findings of its audit of the SBA’s oversight of BLX on its Web site (

www.sba.gov/ig/7-28.pdf

). Though the audit was completed in July, the OIG held it until October, before posting it with heavy redactions. Page after page, paragraph after paragraph was blacked out; printing the document took a heavy toll on the toner cartridge. Why?

Keith Girard described the SBA’s attempted “cover-up” in a December 2007 “Business Intelligence” column posted on the Web site of

The New York Times

:

Customarily, the OIG posts such reports on its Website. But when this one was finished over the summer, SBA General Counsel Frank Borchert asked OIG to either withhold or substantially rewrite it. To his credit, Inspector General Eric M. Thorson and OIG’s own attorneys refused. The standoff ended with a compromise. Thorson allowed the General Counsel’s office to edit, or ‘redact,’ the report.

Such requests are not out of the ordinary. Even though the OIG is supposed to be independent, the General Counsel’s office routinely reviews its reports, and sensitive legal, technical, or proprietary information is often redacted. In this case, however, the editing was so extensive, Thorson felt compelled to add a disclaimer on the cover, a first. Nearly all of OIG’s recommendations, for example, were blacked out.

The report compares BLX’s performance to SBA benchmarks for currency rate (the opposite of delinquency rate), loss rate, purchase rate, and liquidation rate, but the actual data were redacted. So were the details in a section titled “On-site Examinations Noted Material Deficiencies and Instances of Noncompliance with SBA Regulations.” Much of the “Results in Brief” section was blacked out, as well the entire “Chronology of Events.” A discussion of the SBA’s internal risk analysis of BLX was redacted, as was a section titled “SBA Continued to Renew BLX’s Delegated Authority and to Purchase Loans.” The OIG described in its disclaimer, “Since 2001, SBA’s oversight activities identified recurring and material issues related to BLX’s performance. Despite these recurring problems, SBA continued to renew BLX’s delegated lender status and SBA took no actions to restrict BLX’s ability to originate loans or to mitigate financial risks through the purchase review process.” Finally, the SBA’s responses to the OIG’s five recommendations were completely redacted, as was a section titled “Additional Comments.”

It was no wonder the SBA used its black marker. Even with the redactions, it was possible to piece together enough of the audit to see that the OIG was extremely critical of the SBA, saying that the agency was too conflicted (loan portfolio growth versus lender oversight) to act against BLX, even though the agency’s inaction was costing the government hundreds of millions of dollars.

The OIG said the SBA did not accept the results of the audit or implement the recommendations. “SBA management was not receptive to the audit findings and recommendations,” the audit said. The first three recommendations were redacted. The others were to develop standard operating procedures to describe when Preferred Lending Program (PLP) status will be suspended or revoked and how it will be done and to address the conflict of having lender oversight reporting to the Office of Capital Access, which focuses on production volume. Whatever the redacted recommendations were, the report said, the purpose was “to mitigate the risk posed by BLX and to promote consistent and uniform enforcement actions.” The SBA plainly did not see eye-to-eye with its own OIG. Even when the OIG saw the problem for what it was, the SBA itself disagreed and didn’t even want public disclosure—let alone debate—about why it disagreed with the OIG.

Reading between the black, one sees that the OIG found enough recurring problems to question whether the SBA should have renewed BLX’s PLP status for the previous six years. Despite abundant red flags, the SBA did not increase its scrutiny of BLX’s loan purchase requests, even as it paid out $272 million of guarantees. The OIG found that the SBA identified thirty-nine BLX problematic loans and did not resolve “the deficiencies or obtain a repair or denial of the guarantees.”

- “it lacked clear enforcement policies describing circumstances under which it would suspend or revoke delegated lending authority and did not have procedures directing how suspension or revocation would be done.

- “the lender oversight responsibilities of OLO [SBA Office of Lender Oversight] and OFA [SBA Office of Financial Assistance] are not compatible with OCA loan production goals which presented a potential conflict or at least the appearance of a conflict, between the desire to encourage lender participation in PLP and the need to evaluate lender performance and take enforcement action.

- “discontinuing BLX’s participation in PLP and other delegated lending programs would have significantly increased the volume of loans to be processed by SBA field offices at a time when SBA was reducing its loan processing staff in field offices. Also, SBA was attempting to establish the Standard 7(a) Guaranty Loan Processing Centers in Hazard, Kentucky and Sacramento, California, and may not have believed that sufficient staffing would be available to manage the increased loan volume.”

The report said that since the SBA rarely punishes poorly performing lenders by removing them from the PLP program and barely has removal procedures in the first place, lenders have little incentive to behave. “SBA has not developed policies and procedures that describe when it will suspend or revoke PLP authority or how it will do so,” the report said. “Although the current version of Title 13 of the Code of Federal Regulations and SBA’s SOPs contain some enforcement actions, the guidance does not provide direction concerning when and under what circumstances the enforcement actions should be implemented.”

In a damning assessment, the report continued, “Because terminations and non-renewals have not been frequent, lenders can essentially ignore SBA’s delegated lending authority requirements without suffering any material consequences. Therefore, without consistent implementation of enforcement policies, lenders cannot be certain of the consequences of certain ratings; and in addition, they may not take SBA’s oversight seriously.” Seriously.

Besides, the report noted, the SBA has an inherent conflict because enforcement, such as revoking PLP status, hampers the agency’s core function of issuing loans to small businesses. Moreover, kicking a large producer like BLX out of the program would also reduce the SBA’s loan portfolio. “Because BLX has been among the top 10 SBA lenders since 2001, any actions that would appropriately mitigate BLX’s risk, such as suspending its delegated lending authority, also would have been detrimental to achieving SBA’s loan production goals,” the report said.

A week after the OIG published the report,

Dow Jones Newswire

ran a story by Carol Remond, saying that Senator John Kerry, chairman of the Senate Committee on Small Business and Entrepreneurship, was bothered by the redactions. Senator Kerry said in the article: “It is highly unusual for an agency to attempt to withhold the Inspector General’s recommendations and their response from public scrutiny, and the SBA must explain their rationale fully and completely.”

The article said Senator Kerry was “concerned that the SBA is not taking the Inspector General’s recommendations seriously and that it’s not adequately addressing its ‘failed oversight of a small business lender that resulted in years of undetected fraud.’” Remond reported that Senator Kerry said he would soon hold a hearing on the issue.

The article continued, “A spokesman for SBA declined to comment on the extent of the redactions. SBA said in an e-mail statement: ‘Because so much of the material covered in the Inspector General’s report is, by law, privileged and confidential, there is very little we can say about it.’” Remond said Allied also had no comment.

Senator Kerry issued a press release headlined in an extra-large, bold font, “Kerry Questions Bush Administration Decision to Withhold Fraud Findings.” According to the release, “We can’t get to the heart of the problem if the Administration keeps hiding the facts from public view. . . . The Administration must explain their rationale for suppressing the Inspector General’s recommendations and their response. In order to combat future fraud and protect the integrity of this vital small business loan program, the American people need access to all the relevant information.” Senator Kerry didn’t seem that interested in ensuring that proper action be taken to demand full restitution and shut down BLX, but he had no trouble finding his voice to blame the Bush Administration for redacting the audit.

On November 2, 2007, Brickman and I flew to Washington to meet with Ms. Kevin Wheeler, deputy Democratic staff director of the Senate committee, and Angela Ohm, the general counsel for the committee. Though she scheduled us for only a half hour in a conference room, Wheeler was sufficiently interested to transfer us to the cafeteria to complete the discussion when our time expired and the room was needed. We gave them a binder of our BLX findings, including the Kroll report, and explained that we had been complaining to the SBA and SEC for years about BLX. Brickman and I showed her that the fraud far exceeded the Harrington loans, extending nationally and even beyond the SBA to the USDA lending program. We spent time discussing the SBA’s ineffective oversight of its delegated lenders, particularly non-bank lenders. Despite lax SBA oversight, bank lenders perform better than non-bank lenders because more stringent bank regulators review them separately.

We discussed the fact that SBA has faced criticism for years from those who have argued for shutting the agency down outright. The critics argue that in today’s marketplace, small businesses simply don’t need the government to provide subsidies. The original inability of small businesses to obtain loans has long since disappeared, with any number of private lenders ready to finance worthwhile enterprises of any size. In classic bureaucratic fashion, the agency’s defense against its critics has been to go on the offensive, and critics have watched in dismay as the SBA has entrenched itself by expanding both the size of its portfolio and the scope of its services.

In the 1990s, the SBA created new lending programs called SBA

Express

and Community Express. These programs provide government guarantees on smaller loans with reduced application paperwork. According to the SBA Web site, “SBA

Express

was established by the SBA to test the implications of delegating additional authority to selected SBA lenders and of streamlining and expediting the Agency’s loan approval process.” Under the program, the SBA allowed lenders to process loans under $250,000 with even less supervision from the agency. It’s easy to imagine the results of this policy.