Gallipoli (16 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

No one is more relieved than Australia's High Commissioner to Great Britain, Sir George Reid, who has been agitating for this very destination. There has been a dreadful problem with Canadian soldiers behaving badly in the already overcrowded training camp on Salisbury Plain, raising hell in the nearby cathedral city of Salisbury â something Sir George wishes to avoid happening again.

1 DECEMBER 1914, LONDON, LORD NORTHCLIFFE'S TEMPERATURE RISES

The problem?

Real and terrible things are happening on the Western Front, but Lord Northcliffe's journalists are unable to report them accurately in the

Daily Mail

and

The Times

, because the British Government censors won't allow it. American papers report it all accurately, with photographs, and they sell in their thousands, but his papers, and all British papers, are hamstrung from reporting the

truth.

In great frustration, and rising anger, Lord Northcliffe takes pen in hand and writes to one of the more influential figures of the day, Lord Murray of Elibank, that, âWhat the newspapers feel very strongly, is that, against their will, they are made to be part and parcel of a foolish conspiracy to hide bad news ⦠English people do not mind bad news.'

54

EARLY DECEMBER 1914, THE CONVOY GETS CLOSE

And sure enough for the soldiers from Australia and New Zealand, over the next few days it happens before their eyes. First, land appears to starboard, and then to port, and then starts closing in on both sides, a gaping maw of Mother Earth, about to swallow them whole, and they can't wait.

On the blessed night of 1 December, they enter the Suez Canal. Lieutenant Coe records in his diary, âThe marvellousness of it fairly takes my breath away ⦠The first part was just like my idea of Venice.'

55

In the moonlight of an impossibly bright and freezing-cold night, he can see âsentries posted along the banks and then we came to a camp from which we got a good old cheer'.

56

At the gusty break of dawn, everyone is up and about on deck, and the first camp they can see clearly is an Indian regiment who â framed by the pink desert and the Arabian Hills behind, looking down benignly â have secured themselves in a fort of sandbags and barbed-wire entanglements, and who are wildly cheered, just on principle.

âCoo-ee!' the Australians cry. âCoo-eeee! Coo-EEEE!'

57

Goodness gracious me. The Indian soldiers and their English officers swarm from their tents at their call, to roar with laughter and heartily wave back! The men of the British Empire are gathering, and there is an immediate soldierly solidarity between them all, with the Indians smiling and waving in return as these genuine âships of the desert' pass by.

And not just the British Empire. On Banjo Paterson's

Euripides

, the response from a French ship they pass, when the Australian band plays âLa Marseillaise', is inspiring, as the anthem is met with âthe frantic delight of the Frenchmen, who cheered and cheered again'.

58

On they keep moving up the narrow canal, the ship-bound troops fascinated by the steady procession of endlessly interesting things, including many tiny settlements of sad mud huts beside small agricultural patches, where they can see heavily veiled women carrying huge water jars amazingly balanced on their heads, while the turbaned blokes seem to be doing three-fifths of bugger-all as they haul hard on the end of a coffin nail, or kneeling and â¦

And what the hell are they doing

now

? One Australian soldier records his impressions of this soon-to-be-common vision in his diary:

I have just witnessed a tribe of natives paying their tribute to their God the Sun. They looked very funny kneeling and bobbing up and down like a Jack in a box, then they would mutter something to themselves, with their hands up in the air, then nearly knock their brains out with bowing to the sun.

59

This is

weird

, cobber! Somewhere in the distance, some bastard is wailing. The most amazing thing, though? Aboard

Euripides

, it is the vision of a major town on their northern horizon, complete with spires and big buildings, just kind of floating on the shimmer of the far horizon, seen by all, that nevertheless ⦠fades ⦠from view as they approach!

Nothing more than a mirage.

âThis ghostly desert town,' Banjo Paterson records, âmade more impression on the men than anything that they saw; it seemed uncanny.'

60

As the troops remain transfixed by this alien world passing them â at the perfect distance to give them the feeling they are simply watching a film at the cinema â the ships' crews labour to navigate this impossibly thin waterway. Lieutenant Coe, aboard the

Shropshire

, notes his vessel twisting in tight turns and at one point even scraping the side of the canal, as well as another boat, the

Ascanius

. It's ânot as wide as the Yarra', he observes, âbarely half as wide indeed'.

61

Finally, without major damage inflicted, they come to Port Said, at the northern end of the canal. All the ships come roughly together in a wild flotilla, and every soldier who can gets up on deck and exuberantly cheers all the other soldiers on the other ships. As one soldier records, the town âlooks for all the world like a Noah's Ark or a cardboard house constructed by a youngster in its earliest endeavours at house building ⦠Everything is the colour of sand. Even the buildings are sand coloured. It is one of the last places I should hope to be stationed in.'

62

And yet, because Port Said can only cope with unloading two ships at a time, the Australians quickly push on to the bigger port of Alexandria, where a band greets them with a rendition of a new song that has been getting popular of late, âAdvance Australia Fair'. The men then have to make their way through hundreds of young Arab urchins â boys and girls â begging them for baksheesh. Just beyond, hundreds of peddlers and hawkers want to sell them everything from wheelbarrows to cart their gear in, rings and jewellery taken straight from the tombs in the pyramids, an original piece of the cross that Jesus Christ was crucified on, to one of the

actual

30 pieces of silver that Judas was paid off with. Yours, for just 50 piastres, a little less than half a pound!

Later, one of Trooper Bluegum's cobbers, Trooper Newman, will pay ten piastres for a handkerchief that has on its four corners images of King George, Lord Kitchener, General French and the Commander of the Grand Fleet,

63

Admiral John Rushworth Jellicoe, while all over it are dukes and earls. âIt may be the only chance I'll get,' Trooper Newman says, âof poking my nose into high society.'

64

All over the quay are low four-wheeled carts â measuring about three feet by eight feet â attached to what the troops instantly begin referring to as âArab stallions' but are in fact donkeys. Well, here are some of

our

animals. Though the koalas and possums smuggled aboard by the Australian troops have perished on the trip over for want of the right food â and at least one of the kangaroos had taken one big jump too many, to finish in the middle of the Indian Ocean â here now is a surviving Old Man Kangaroo, who

refuses

to budge from the wharf. And nor does Old Man particularly care for the large crowd of Egyptians who have gathered to see the newcomers and are now staring with sheer amazement at this

extraordinary

-looking creature.

Open-mouthed they stare, while the kangaroo merely glances at them. (If you've spent six weeks on a troopship with a thousand Australian soldiers, you have pretty much seen it all anyway.) But perhaps they might be worth a closer look? Alas, when the kangaroo takes just a couple of bounds in the direction of the gathered natives, it is met with a melee of madness as, with âear-splitting yells, some hundreds of Alexandrians made record time in seeking safety from the “ferocious” beast'.

65

Even the smaller scrub wallabies are viewed as demons in disguise by the natives: âOne fellow the wallaby chased and he dropped all his tomatoes and fairly screamed and called upon “Allah” to save him, for surely he thought the devil was on his track.'

66

Ah, how the Australians laugh. These âGyppos', as they are already referred to, would run away from anything.

Within three hours, the soldiers are on the train, steaming south through the Delta country on the 120-mile trip to Cairo, and the farmers among them are particularly impressed. One soldier records, âThe intense cultivation of the Delta was a great surprise to us.'

67

Others, such as the softly spoken cove from Sydney, Sergeant Archie Barwick of the 1st Battalion, look out the window as wide-eyed as when they had first approached Suez. âI fairly drank it all in,' he recalls, âfor we were now in the land of mystery and wonderful things.'

68

âThe native villages are most peculiarly laid out,' noted Warrant Officer Frederick Forrest, âand the method of tilling the land somewhat strange to us Australians. It is quite common to see an ox and a camel, or a camel and a donkey pulling an old wooden plough.'

69

Wooden ploughs! Just how primitive is this country?

Pretty primitive, cobber. Look over there, with mum, dad, grandma and three kids travelling on two camels, all eating from the same cabbage that they are feeding to the goats trotting along behind â¦

As the soldiers pass, they see âstrings of camels proceeding in leisurely fashion, the riders being Arabs in flowing garments and gaudy turbans or Fez caps'

70

looking, in the words of Charles Bean, as if they âmight have stepped out of the Bible'.

71

At least, however, the purpose-built siding for the Australian troops just off Cairo Central Station is modern, having been completed only in the past few days. After the men arrive there at 10 pm, the next thing is to transfer their supplies and gear into trams, donkey carts, mule wagons and army transport carts escorted by magnificently uniformed Egyptian Mounted Police, while by the light of the moon they must march off on the road parallel to the tram track, west then south to where their training camp lies, at Mena, ten miles away.

To get there, they must take a bridge across the mighty ribbon of the Nile, and as they approach it â marching behind their band â the Australians pass some yellow plastered barracks where the just-arrived Lancashire Territorials of the 42nd Division are quartered. Woken by the band, those worthies tumble from their bunks and rush across the gravelled parade ground. âWhen they found that the troops marching past them were Australians,' Charles Bean would record, âthey cheered, clinging to the railings and waving.'

72

Hurrah! Hurrah! Hurrah!

Some five miles of marching later, the men catch their first glimpse, and the gasp goes up. The pyramids! I can see pyramids by the light of the moon, pyramids so big their tops poke out above the fog that has settled on the desert floor.

Is it yet one more mirage?

No, mate. The camp for the Australian soldiers lies in a desert valley within coo-ee of the towering 482-foot Great Pyramid of King Cheops and his lesser brothers â and all who see the pyramids are astounded, Bluey, by their sheer

bulk

.

Of course, no tents have been erected for the new arrivals in their camp, nothing prepared, so they simply lie on the soft sand and sleep the best they can â for, in the very words of many a man in those wee hours, it is cold enough to freeze the balls off a brass monkey. Who knew the desert could be so cold at night?

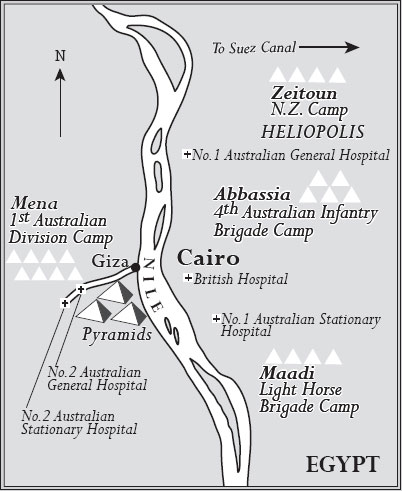

Cairo district army camps and hospitals, by Jane Macaulay

A MAN WITH A PLAN â¦

Are there not any alternatives than sending our armies to chew barbed wire in Flanders? Further cannot the power of the Navy be brought more directly to bear upon the enemy? If it is impossible or unduly costly to pierce the German lines on existing fronts, ought we not, as new forces come to hand, to engage him on new frontiers �

1

First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill to Prime Minister Asquith, 29 December 1914

MID-DECEMBER 1914, CAIRO, IN THE SHADOW OF THE PYRAMIDS

For the imperious Sphinx, this is nothing new under the searing sun.

For nigh on 45 centuries, it has gazed indifferently on the sweaty military men marching before it: on the way to battle, on the way from battle, preparing for battle. True, these particular men, from Australia and New Zealand, have come from further away than ever before, and their battle is set to take place somewhere unknown, but much of the rest is the same. The men stagger back and forth, they are shouted at, they curse when they are sure their officers can't hear them, they stagger, they occasionally faint and tumble down to the hot sands below.

Ah! That sand! In an instant, a faint breeze becomes a sandstorm. âImpossible to keep the sand out,' one young Australian private notes in his diary. âTiny particles found their way through the fabric of the canvas [of the tent] and in a few minutes there was a yellow layer of sand over everything. At dinner, the stew looked as if someone was continually shaking a pepper pot over food and you could feel the sand going down the throat. Through eating and inhaling fine particles of sand, hundreds of the men soon developed what was dubbed “The Pyramid Cough!”.'

2

For most of the Australian soldiers now settled into the endless line of sandy tents in the desert that is the Mena Camp â while the New Zealanders are in Zeitoun and the Light Horse in Maadi â the strangeness of the environment is soon matched by the sense of time. Is it really only six weeks ago that they left Australia and all that was familiar to them? It now seems so long ago â another world, another life.

For every day starts with reveille at 5 am sharp, the sound of the bugle whipping across the desert sands and through their thin canvas tents before drilling right into their ears.

Up! Up! Up!

Rise and shine!

Shine like the scorching sun, which, even early, belts down upon them as they devour a quick breakfast of eggs, and bread and jam. Many of the men are not adapting well to the produce of this strange land and are grateful when, after some time at the camp, some of their food starts arriving from home. As Lieutenant Coe later records, in the rough manner of speaking that breeds freely among the men in the camp, âWe get Australian butter, which is much appreciated. The Arabic butter being too much for our palates. Rancid always ⦠We also get Australian eggs, which is a huge boon, as the native eggs taste like a nigger smells which is not nice.'

3

(Less appreciated are the cans of bully beef coming from home, which you practically need a hammer and chisel to penetrate.)

At 7.30 am, they fall in for the first of many inspections and roll-calls for the day. And then to the serious stuff.

Their exercises include digging trenches, attacking a hill under heavy fire, retreats, outflanking opposing battalions and marching in full kit for staggering distances, before marching back again, staggering still more. Yes, they have a small break at high noon for lunch, but when that consists of a small tin of sardines and a small roll of bread shared between two men, it is no wonder one of their favourite marching songs is âThe Brigadier gets turkey / The Colonel he gets duck / The officers get chicken / And think themselves in luck / The Sergeants get their belly full / We watched them through the wall / But all the poor old Privates get / Is one dry roll.'

4

On their marches into the desert, they must look out for big rocks that, between them, they can carry back, paint white and then use to mark out their territory at Mena Camp.

As the always diligent Charles Bean records, often spied with his pad in hand, jotting notes all the while in his mad dash of a scrawl, âAll day long, in every valley of the Sahara for miles around the pyramids, were groups or lines of men advancing, retiring, drilling, or squatted near their piled arms listening to their officer ⦠At first, in order to harden the troops, they wore as a rule full kit with heavy packs. Their backs became drenched with perspiration, the bitter desert wind blew on them ⦠and many deaths from pneumonia were attributed to this cause.'

5

Meanwhile, the troopers are equally busy with their own training regime, endlessly taking their horses on long treks through the desert to toughen both horse and rider before making rapid attacks on a designated sand hill three miles away, and dismounting and firing a dozen times, before fixing bayonets and charging, and so on and so forth as the sun blazes down and they can return at the end of the day before the Sphinx that still never blinks at their effort.

As to the signallers, they too are flat out refining their methods of communicating over great distances by use of heliographs and flags â the former using flashes of reflected sunlight to communicate by Morse code, and the latter waving flags in both hands in such a manner that each double movement spells out a letter that another signaller can interpret. And even then, once the men are back in camp, there are frequently night manoeuvres to engage in, charging around in the desert moonlight until as late as 11 pm.

Inevitably under such hardships, strong friendships are formed between the soldiers suffering together, united in their common detestation of the Brass, the beggars and the endless cans of bully beef, known by them as âtin of dog'. All together, the soldiers are what they sometimes refer to as âF.F.F.' â âfrigged, fucked, and far from home'.

6

For the gunners, there is also firing practice, and if the Sphinx is seen to wince at this, it is likely because, at least as local legend has it, just over a hundred years earlier the troops of Napoleon Bonaparte had shot off the Egyptian equivalent of a âbullseye' â the nose of the Sphinx â while engaged in target practice.

Bit by bit, things start to gel. When the men had started this caper, they had been a motley mix of teachers, timber-workers, carpenters, con men, lawyers, labourers, illiterates ⦠and, yes, perhaps a few reprobates and troubled souls eager to take this well-paid opportunity to get away. Now what are they? They are men of the Australian Imperial Force. Over the weeks, a certain

âspray de corpse'

â or whatever that French saying is â grows up between them.

Being Australians, there is always time for levity, no matter how exhausted they are. On one occasion, a company from the battalion of one of the AIF's most famous characters, Lieutenant-Colonel Pompey Elliott, are on the march near Cairo when they pass by a group of hawkers and their donkeys.

Left ⦠left ⦠left, right, left â¦

At that very moment, a male donkey becomes excited by a nearby female donkey, and the impressive manifestation of that excitement makes the soldiers roar with ribald laughter. Annoyed, the nearest hawker gives the donkey's ear a vicious twist, whereupon the lateral tension of the situation instantly dissipates.

Just a few minutes later, the Captain of the leading company is striding out, closely followed by his Senior Sergeant and the men when â

hulloa!

â here comes a carriage bearing two beautiful Englishwomen.

Company ⦠Halt!

As one of the women smiles coquettishly at the handsome Captain, and he returns an enthusiastic salute in kind, a loud but laconic drawl comes from deep within the ranks: âTwist his ear, Sergeant.'

7

As for leisure time, there is frankly not a whole lot of it, but sometimes in lunch hours the men have such things as races between âArab stallions', with four or five men going up against each other over a circular course, while the rest whoop like madmen

8

â before a fresh batch of soldier âjockeys' try their luck. Ah, how they laugh!

Another beloved activity is recorded by young Trooper Percival Langford: âJust along side us are the pyramids. When you read about these things they are not usually retained in the memory, but when you actually see them you don't easily forget. At the very first opportunity we set out to climb the first of them ⦠The view from the top is glorious.'

9

From there, they can gaze east at the shining ribbon in the desert that is the Nile River, festooned with the âwhite wings gliding up and down [of] the triangular sails of the native dhows'.

10

Some enterprising Gyppos have even set up a small stall at the top, so the soldiers can enjoy the view while sipping on soft drinks and coffee.

Nothing, however, is more popular than taking the quick tram ride into exotic Cairo. Most particularly, they love to visit âthe Wazza', the red-light district. The most cosmopolitan place in an already extraordinarily cosmopolitan city, its narrow, winding streets are filled with Persians, Syrians, Sudanese, Armenians, Turks, Italians, Greeks, Arabs, French and other nationalities from all parts of the world. It is filled with hawkers and peddlers of all kinds, imploring the soldiers to buy their wares and always greeting them with such calls as âAustrali very good, very nice ⦠Plenty money Australi â¦'

11

and âWALKING STICK! Cigarette flag! Cigar, pos'card! B'ery goo-o-d!!! B'ery nice. Australia, b'ery goo-o-d! Baksiesh. Gib itâ'alf piastre â¦'

12

One shopkeeper is insistent: âDon't go elsewhere to be cheated, Australians. Come here!' While another puts a sign out the front proclaiming to all:

Â

ENGLISH AND FRENCH SPOKEN;

AUSTRALIAN UNDERSTOOD.

13

Â

And the Australians in turn even learn a few words of Egyptian, such as â

saieeda

' for âgoodbye', â

yallah imshi

' for âgo', and, most importantly, â

bint

' for âwoman'.

14

For the most potent attraction of the Wazza is that it is

filled

with them â young women, old women, fat women, skinny women, perfumed women â¦

available

women.

They titter and teeter out from the balconies of the three-storey villas that lean towards each other over the streets, wearing dressing-gowns that tantalisingly flap open. They stand in doorways, they congregate in bars, they coquettishly flutter and flirt and flounce ⦠and, most importantly, they root like ginger for as little as five or six âdisasters' (piastres), the equivalent of just a single shilling! And, of course, they want the Australians most of all, because these boys are the best-paid soldiers of all, on six shillings a day â even if one shilling a day is held back on a savings plan â while their British equivalents are on just a shilling. As to the New Zealanders â who prove to be not bad bastards, though it sounds like they trod on their vowels â they are on five shillings, while the French earn the equivalent of two shillings a day and the Indians get approximately a fifth of fuck all.

Helping to make the Australians feel rich, able to toss their money around like drunken sailors, is that they are actually paid in piastres, absurdly tiny coins that don't actually feel like money at all. And why not spend it in the Wazza? While a man can't buy any legal grog in Cairo after 6 pm, at the Wazza the beer flows all day and through the night, and let a man get a skinful of their particularly strong beer and

then

see how he goes resisting these sinful bints.

But still he is not weakening, you say? All right, then let him go to one of the cancan halls, where he can see a dozen or so women dancing totally

naked

â for many of the soldiers, the first nude women they have seen in their lives â and then see what happens! Mate, for just a few piastres, you can

touch

them, you can reach out and feel their swaying buttocks and pendulous breasts, and who can resist that? Not me, and not many.

As Sergeant Archie Barwick writes, âOnce inside these dens unless you have a very strong will, you are done for. They are places of the vilest description where the inmates would sell their soul for sixpence.'

15

And, yes, maybe these whores are the cast-offs from the Marseilles brothels, in for stints as bints, for a bob a job on their backs in Cairo ⦠before they're also kicked out of here to end up in the whorehouses of Bombay, but so what? Apart from the fat Nubian Ibrahim al-Gharbi, who is the King of the Wazza â a weird one who dresses in women's clothing and wears a white veil â there really isn't much other authority, and you can do what you like. (The one exception to this absence of authority proves to be a beloved Salvation Army chaplain, the Reverend William McKenzie â chaplain to the 4th Battalion, soon to be known as âFighting Mac' â who regularly goes to the Wazza to drag drunken Australians out of the brothels and put them on the tram back to camp, before they can disgrace themselves.)

It's not just the alcohol that is intoxicating, though, it is the

feel

of the whole place: the perfume, the pimps, the passers-by of all descriptions, the music, the laughter, the squeals of delight and debauchery, the excitement, the sweet smell of hashish, the bloody fights that take place as you dodge the pools of vomit from other blokes who have gone before you and avoid ever more bints grabbing you by the hand to see if they can drag you upstairs. It's the sheer

thrill

of it, as you go looking for that Upper Sudanese woman they're all talking about, who is as black as the devil's hooves, stands six foot seven inches tall, and bangs like a dunny door in a hurricane!

Mate, you go to the Egyptian Museum if you must and look at your mummies, or search for that ancient sycamore tree in Heliopolis where they say the Virgin Mary rested on her way from Bethlehem to Egypt.

16

Me and the other blokes have no interest in mummies or virgins of any description and are going back up the Wazza to see the brown girls with the rosy red cheeks! And, yeah, I may even have another go on a rancid mattress, with the same bint as last time, but you can keep your sermons. I wanted my first time to be with sweet Annie from back home in Gunning, but it just hasn't worked out like that. If you and I are going to maybe die in battle, I, at least, won't be

dying

a virgin like

you

.