Gallipoli (20 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

To his dismay, everything is so badly organised that his introduction draws nothing but blank stares. Kemal is embarrassed, being made to feel âalmost as if I was playing a confidence trick on them'.

67

Within the coming days, he learns that his division is being formed at TekirdaÄ, on the north shore of the Sea of Marmara, an area he is familiar with from his days in the Balkan Wars. Quickly, he begins his preparations to join them.

âTHE FATAL POWER OF A YOUNG ENTHUSIASM'

So, through Churchill's excess of imagination, a layman's ignorance of artillery, and the fatal power of a young enthusiasm to convince older and more cautious brains, the tragedy of Gallipoli was born.

1

Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914â1918, Vol. I

It is my hope that the Australian people, towards whom I have always felt a solemn responsibility, will not rest content with so crude, so inaccurate, so incomplete and so prejudiced a judgement, but will study the facts for themselves.

2

Churchill in reply, The World Crisis, Vol. II

28 JANUARY 1915, WAR COUNCIL MEETING

Bloody Winston!

For Churchill starts pushing it again, doesn't he? With other members of the War Council backing Churchill, Sir John Fisher can no longer stand it and breaks his âobstinate and ominous silence'

3

to vigorously protest.

Now former Prime Minister Arthur Balfour is going on, waxing lyrical about the virtues of such a naval attack on the Dardanelles:

âIt would cut the Turkish army in two ⦠It would put Constantinople under our control ⦠It would give us the advantage of having the Russian wheat, and enable Russia to resume exports ⦠It would also open a passage to the Danube.'

4

Sir John Fisher can no longer bear it. All these things might be true

if

the fleet gets through, but that is simply

not

going to happen. He decides on the instant to resign and is starting for the door when he espies Lord Kitchener looming large off his starboard quarter, closing fast and clearly preparing to engage.

Now.

Clutching the older man by the elbow, Kitchener pilots him towards the shelter of the bay window, where the two can talk quietly.

Within ten minutes, Sir John Fisher has been warped back into his original berth and the meeting, which has not paused for an instant, continues.

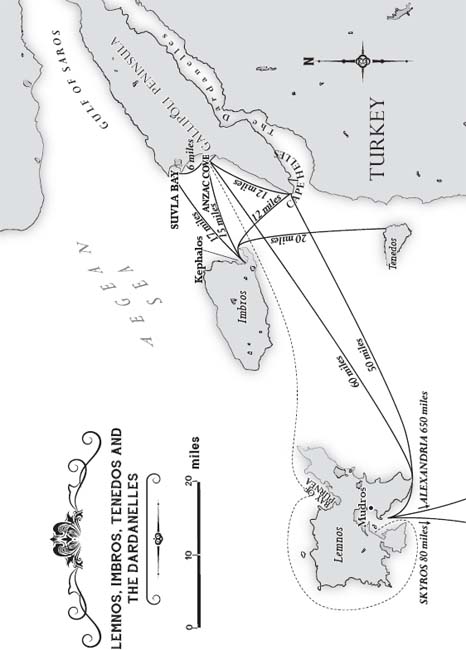

Taking up the cudgels, Admiral Sir Henry Francis Oliver announces that the first shot could be fired in about a fortnight and that ships are already on their way. By the time of the attack, they would have no fewer than 16 destroyers, 24 French and 21 British minesweepers, and other small craft. For a forward naval base they have decided to use Port Mudros on the Greek island of Lemnos (which was taken from Turkey in 1912 and which the Greeks will surrender under âprotest' to retain their neutrality), situated some 50 miles from the mouth of the Dardanelles.

LATE JANUARYâEARLY FEBRUARY 1915, SUEZ CANAL, HERE AT LAST

Those who thought the âunspeakable Turks' incapable of crossing the Sinai Desert to threaten the Suez Canal have been proven wrong. Yes, the Ottoman Empire has fallen on hard times, but it has enough kick left that it is

still

capable of driving major military forces over great distances, and one of them now stands, threatening the Allied defences at the canal itself, near Ismailia on the west bank.

Hence why Captain Stoker and the crew of the

AE2

are rushing through the canal at a pace of 14 knots instead of the peacetime speed of six knots. Stoker had been so keen to get through, come what may, that he had not even waited for permission, despite the risks. Arriving at the top of the canal at Port Said, Stoker is thrilled when âorders unexpectedly come to join the Fleet off the Dardanelles',

5

and the

AE2

makes for the Greek island of Tenedos.

Lemnos, Imbros, Tenedos and the Dardanelles, by Jane Macaulay

The rest of the convoy, meantime, bearing Colonel John Monash and his men, push on to Alexandria and then back to Cairo, where they are soon settling into Mena Camp with the other Australians.

General Birdwood (just anointed, if you please, as

Sir

William Birdwood, Knight Commander of the Most Exalted Order of the Star of India) and his senior officers are impressed with both Monash and his men â the latter generally being Australians of more substantive positions than those in the 1st AIF, who had taken a little more time to extricate themselves to become soldiers of the King. And they are physically superb, with Charles Bean noting, âThe huge men who at this time began to appear in the streets of Cairo gave the appearance of being built, if anything, on an even larger scale than those of the first contingent.'

6

But, just like the 1st Australian Division, they are mostly stunned by their surroundings, though there are a couple of exceptions.

One soldier from Oodnadatta says he is most disappointed by the desert, declaring, âIt's not nearly as bad as the salt plains in my own home run.' Not to be outdone, another soldier says that the compressed carriages on the Egyptian trains make him feel quite homesick, though they are âcertainly a little more comfortable than the dog-boxes in which I travel to work in Melbourne'.

7

As to the new arrivals, they are impressed with just how fit, strong and trained those of the First Divvy look, for there is no doubt that all the training these coves have been doing for the last five months, and most particularly in the last six weeks, is paying off.

And that training is never more intense than right now â¦

To give the 1st Infantry Brigade experience in night attacks, on 8 February they are marched to a place eight miles from Mena, high up the Nile on the edge of the desert. For four days and nights, almost continuously and with Charles Bean in close observance, the brigade goes through an endless series of sham-fighting and entrenching.

âIn the short rushes of the final night attack,' Bean would record, âthe men, when they flung themselves down to fire at the end of each advance, dropped fast asleep. In some cases the next line found them in that state when it came up, and nudged them to go on again.'

8

And yet the 3rd Brigade is even more impressive. They are engaged in a field day in the desert under their British Commanding Officer, now seconded to the Australian Army, Colonel Ewen MacLagan, when a sudden command is given that requires them to shift from their present location towards where MacLagan and Bean are standing, looking earnestly in their direction as the sun beats down. Two of the battalions are so far away in the desert, just this side of the horizon, that they appear as no more than a few vague dots, treading the silvery line where earth meets sky and mirages are born.

The British officer MacLagan has enough experience to know that at this distance it will be at least 15 minutes before they arrive and â¦

And what is this?

After just a few minutes, the dots thicken, enlarge, take shape ⦠They are men. Big men. Running hard, the sweat coursing down their dusty faces in rivulets. They are the 9th Battalion â Queenslanders â coming on strong in a cloud of dust of their own making, like a boom of angry thunder rolling across the desert.

As they run past, Bean looks at his watch and shakes his head in wonder. It has taken them just

eight

minutes.

Only one machine-gun section remains out there ⦠and here they are already, hauling their 30-pound Vickers machine-gun, a few of them lugging the even heavier 50-pound tripods on their burly shoulders, others the ammunition. Still others tote different guns as they all keep charging through the deep sand.

âHurry up! Double up!' cries the officer, and so they do, throwing some of the gear straight into the waiting wagons while being careful with the more delicate instruments.

âCome on!' the officer roars again. âWe can't wait to lower that elevating screw.'

Within a minute the machine-gun detachment has departed, as Bean would describe, âdown the dip, the horses trotting, the men holding on to the carts or running behind â fading fast in their own dust'.

9

Who knows what kind of action these men will see, but they look fit, strong, well trained and

dangerous

. And MacLagan â a thoughtful veteran who had served in India and the Boer War and is a natural leader of men â has clearly done an outstanding job in training them. (The only soldiers that come close are the men of the Wellington Infantry Battalion, where Colonel William Malone has continued to work them till they drop, weeding out all those not up to his rigorous standards.)

Tragically, other Australian soldiers have been judged at this time as principally a danger to themselves and those around them and, just as General Bridges had warned Charles Bean, are sent packing in disgrace. No fewer than 301 Australian soldiers â many suffering from VD, but 131 guilty of ill-discipline in many forms â are expelled back to Australia aboard the troopship

Kyrra

. Those with VD â mostly gonorrhoea, syphilis and genital warts â are kept in strict isolation. Their pay has been stopped, their pensions cancelled, their families informed of the reasons for their return and their names published in the papers. When they get to Australia, they know they will be kept in âan isolation camp at Langwarrin'.

10

They, and all the others, will be dishonourably discharged.

8 FEBRUARY 1915, ALBANY, THE 10TH LIGHT HORSE REGIMENT, AMONG THE SEAHORSES

As the hot sun of the long day starts to wane, it is almost time to go. At last, after four months of training, practising their drills, bringing themselves and their horses up to the keenest pitch of fitness, the HQ, together with A and B Squadrons of the 10th Light Horse Regiment, is ready to leave Western Australia and head to Cairo, where in time they will meet the rest of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade.

Surveying them all, their Commanding Officer, Lieutenant-Colonel Noel Brazier, could not be prouder if they were his own sons. Alas, his admiration for the regiment is not universal, and just as

Mashobra

pulls away 'neath the caterwauling seagulls, and all the men are waving to their families, at this poignant moment

â should auld acquaintance be forgot, and never brought to mind â

the newly arrived Second-in-Command of the 3rd LHR Brigade, 49-year-old Brigade-Major Jack Antill, outflanks Brazier and attacks from a totally unexpected quarter. âThis,' he yells, âis the worst disciplined regiment I have ever seen!'

11

Now, the Brigadier-Major doesn't slap Colonel Brazier in the face with his glove as he says it, but he just as well might have. Brazier keeps his own counsel â just â knowing that if he allows himself to speak, the torrent of vitriol he has inside will blow like a volcano. But still Antill does not calm and a short time later makes further nasty remarks about Brazier's men.

As Brazier and others in the 3rd LHR Brigade quickly come to understand â though not excuse â this is simply Brigade-Major Antill's nature, just as a bird flies and a fish swims.

Hailing from Picton in New South Wales, Antill has been a professional soldier all his life â he was very likely

born

a soldier â and it is not for nothing that they call him first âBull' Antill and then âthe Bullant'. For just like a bullant, Antill is aggressive, military by instinct and exclusively

militant

in his approach to all problems. There is no problem so great that a bigger hammer and a louder voice can't fix in the short term. In all of the brigade there is only one man he defers to â and even then, only just â and that is 57-year-old colonial Frederic Hughes, described with rare dismissiveness by Charles Bean as âan elderly citizen officer belonging to leading social circles in Victoria',

12

as in, his appointment has absolutely nothing to do with any military acumen he has ever displayed. Though Hughes certainly looks the part of a military man, with a world-class moustache, impeccable uniform and a back so straight it would put a ramrod to shame, he has never actually fired a shot in anger on a battlefield, nor been fired upon. He is obsessed with the form of the military, with no experience of the fury.

And so, while the driving force of the 10th LHR remains Brazier, the man presiding over the 3rd Brigade is the Bullant. As those men will all soon learn, he does not smile, he snarls. He does not converse, he dictates. He wants all the troopers in his brigade to hear him and

fear

him.

The Bullant is, in fact, just the kind of man that Colonel Noel Brazier most detests, and he has done so from the moment he met him ⦠to save time. It is a detestation matched only by the one Antill feels for this Brazier upstart.

MID-FEBRUARY 1915, MENA CAMP, THE NEWS BREAKS

Have you blokes seen this? It's that bastard war correspondent, Bean, and he's been writing terrible things about us in Australia. Me dear old mum just sent me a copy, and she is none too impressed. Just read some of it!

Copies of the article coming back to the soldiers are passed from hand to hand, and the outrage grows as they see their names so slurred â¦

WASTERS IN THE FORCE.

SOME NOT FIT TO BE SOLDIERS.

13

That

bastard!

Charles Bean â mortified, finding himself crudely insulted by passing soldiers, with even threats that âas soon as we get into the fighting, you will be shot'

14

â pens an open letter, pointing out that he was really only talking about a small minority. But this does not mollify one Sergeant Westbrook, who is soon widely published in the newspapers back home.

On Our Critic's Apologies

⦠So you say you're sorry, Mister?

We sincerely hope you are,

And we trust you'll tell our loved ones

In our southern home afar.

So just set your pen a jigging,

Write and never mind the rest;

But inform them all sincerely

We're behaving just the best.

There's a few we know who's throwing

Mud upon Australia's name;

But the rest's not going to carry

All the burden of their shame â¦

15