Gallipoli (34 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

WEE HOURS, 25 APRIL 1915, CAST OFF AND DRIFT ASTERN

Bearing the bulk of the First Wave's 3rd Brigade now transferred to their care, the seven destroyers' screws turn languidly, as the black silhouettes of the flotilla bearing the Anzacs now approach the rendezvous point off the shores of the Gallipoli Peninsula.

Just a little back from the main flotilla, the Australian submarine

AE2

is also making its careful way. An attempt to go through the Dardanelles the previous evening had had to be abandoned after the âforemost hydroplane shaft coupling' broke.

13

But, mercifully, Rear-Admiral John de Robeck is allowing Stoker to make another attempt. âTry again tomorrow,' he had said. âIf you succeed in getting through there is nothing you could possibly want that we won't do for you.'

14

This time, however, the orders are different. Yesterday, the hope had been that the sub would make it through the Narrows into the Sea of Marmara and then attack the shipping bringing supplies to the Turkish troops. Now, as the sub would be in operation when much of the fleet would be lying off the entrance to the Straits, it is crucial that the Turks be prevented from floating mines down on the current, which might see the Allies lose ships as they had done on 18 March. Commodore Roger Keyes, de Robeck's Chief of Staff, had told Stoker, âIn fact, generally run amuck at the Narrows â if you get there.'

15

If

you get there? Stoker had burst out laughing. But the rest of it had been no laughing matter. For the order â and Stoker well knows it â means that he and his men are unlikely to come back. While it would be one thing to get through the Narrows to the Sea of Marmara and hunt like a fox for the fat rabbits of supply ships â for preventing the Turkish defenders getting resupplied easily by sea is the key aim â it would be quite another to hunt in the tiny alley that leads to the rabbit nest itself. There, the submarine risks being the rabbit in the searchlights, while all the forts, patrol boats, cruisers and destroyers would be able to bring concentrated fire to bear.

âIf you searched the whole world over,' Stoker would write, âI doubt you would find a much more unpleasant spot to carry out a submarine attack than this Narrows of Chanak. Half a mile wide, with a current of 3 to 5 knots, it is certainly not an ideal place for manoeuvres in a comparatively slow-moving and difficultly turned submarine. Also, the thought that we ourselves might meet one of those floating mines hardly added to the entertainment the day was likely to provide for us.'

16

Carefully, slowly, the great battleships continue to steam towards the Turkish shore. For those soldiers awake above decks, all that can be seen is the slightly darker blobs of the other destroyers. Some men take up their âmandolins, guitars and banjos' to play and sing with a gathering chorus, which withers into silence as the night grows older. Some men talk quietly, careful not to wake those who have snatched a final sleep. Face to face with their mortality, the men abandon nicety and share astounding stories and âhome truths' with each other, divulging secrets they never knew existed.

17

At 1 am, there is a stirring among the men as, even though asleep, they become aware of a change in the rhythm of the ship's engines, which slow to nearly nothing. They are here, at the designated rendezvous point, just five miles from the spot where the men are to land. Across all the ships, those soldiers remaining asleep are woken â âCome on, lads, have a good, hot supper, there's business doing'

18

â and given a hot meal of (they knew it!) bully beef and bread, washed down by the second-greatest Australasian restorative of all: a cup of piping-hot tea. On some of the ships, the men are given a tot of rum to settle their souls and warm their spirits.

Aboard

London

, the soldiers have hit it off with the sailors â so much so that the sailors have ârenamed Port and Starboard as A and C after the two Australian companies on board'.

19

Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett wanders around the mess deck with his notebook, observing the soldiers wolfing down their meals, while their officers dine in the wardroom. Yes, perhaps the Last Supper for some, but the Australians are âas calm as if about to take part in a route march'.

20

At 2 am, right on schedule, the hissed order goes out on deck to

âPrepare to man the boats â¦'

, even as the men eating their meals below hear the command ringing down the ladder-ways:

âFall in!'

21

And so they do, taking their rifles and their packs, climbing the ladders and forming up into companies by going to their assigned squares on the deck, each of which has a large painted number on it. From the derricks, the ships' boats are now lowered, and rope ladders thrown over the side, while the ships turn parallel to the shore to shield sight and sound from those who may be carefully watching and listening â¦

âWith only a faint sheen from the stars to light up the dramatic scenes on deck,' Ashmead-Bartlett observes closely. âThis splendid contingent from Australia stood there in silence as the officers, hurrying from group to group, issued their final instructions. Between the companies of infantry were the beach parties, whose duty it was to put them ashore. Lieutenants in khaki, midshipmen â not yet out of their “teens” â in old white duck suits dyed khaki colour, carrying revolvers, water-bottles, and kits almost as big as themselves, and sturdy bluejackets â¦'

22

Now in all but complete darkness â even smoking is banned â the Australian soldiers get their rifles on their shoulders and, with their hearts in their mouths, climb onto the swinging rope ladders that dangle into the boats below, only barely bobbing in water so calm that it is âlike a sheet of oil'.

23

There in the light mist, four midshipmen and one coxswain await in the boat below, whispering respectfully to the lightly growling officers on high how many more they can take â it is up to 40 soldiers to a boat, taking some 40 minutes to load â until one gives out the much-awaited last whisper, âFull up, sir!'

24

Very well, then.

âCast off and drift astern,' comes the next command from the shadowy figure on high.

In the boats â amid all the boxes of ammunition, picks, shovels, sandbags and wire-cutters, among other things â the soldiers of the 9th, 10th and 11th Battalions shiver. They have been told not to wear their great-coats, for they are too cumbersome and it is thought their exposed white skin will help them to keep track of each other once on the shore.

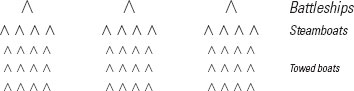

The three battleships begin to tow their four steamboats and attached boats carrying a total of 1500 soldiers in this, the first lot of the First Wave:

At 2 am, just as the Australian troops are preparing to launch their boats, two Turkish soldiers are sitting in their observation post on a ridge above Ari Burnu, the very spot that the companies of the 3rd Brigade are approaching. Both local boys, Idris from Boghali and Cemil from Gallipoli, they chat quietly, smoking and occasionally taking up their binoculars to scan the western horizon, far out across the moonlit waters, where there is nothing but â¦

Bismillah ⦠Bu ne?

My God ⦠what is that?

What?

There!

THERE!

And now Cemil can see it too.

Way, way out, in the sliver of silvery light where the sky meets the sea, they can see distinct shapes.

Ship

-like shapes!

Ingiliz! Ingiliz!

There are ships! Many, many ships! English soldiers are just off our shores!

Immediately, the two sentries report to the Company Commander.

Captain Faik, Commander of a company of 250 soldiers in the 27th Regiment, is sleeping in his dugout on the Second Ridge when a sentry from his reserve platoon bursts in and awakens him.

Ingiliz! Ingiliz!

The observation post has spotted âmany enemy ships in the open sea!'.

25

Captain Faik immediately rises and surveys the sea using his own binoculars.

Aman Allahım!

Oh, Allah!

There they are, all different sizes, bobbing in the moonlight a fair way offshore. He can't tell if they are moving or still, but they are definitely there in force.

Quickly, he gets his Battalion Commander, Major Ismet at Gaba Tepe, on the telephone and reports what he has seen.

âThere is no cause for haste,' the Major's voice crackles back down the line.

26

For now, Captain Faik is to continue watching closely and report back.

Peki, Komutan

. Of course, Commander.

Racing to his observation post, the captain tries to steady his raggedy breathing as he again brings his binoculars to bear and ⦠this time there is no doubt about it. The ships are a great mass now,

dozens

of them, and they are much closer, heading straight for the shores right in front of where he is now standing.

With some trepidation, Captain Faik phones straight through to divisional headquarters near Maidos. He reaches Lieutenant Nuri and reports what he has seen.

â

Telefon baÅından ayrılma

â Hold the line,' Nuri replies. âI will inform the Chief of Staff.'

It is an agony. With every second that passes, the ships are coming closer and will no doubt soon be disgorging enemy soldiers, but Captain Faik waits until Nuri returns.

âHow many of these ships are warships,' he asks, âand how many are transports?'

âIt is impossible to distinguish what type of ships they are in the dark, but there are

many

of them.'

27

The conversation ends there and, for a moment, Captain Faik sits on the ridge above the quiet cove, alone, looking out at the approaching fleet in the fading light of the setting moon. They are closer still, fading into darkness as the moon begins to set â¦

At the same time that the men of Turkey's 27th Regiment's 2nd Battalion are being woken up and called to arms, the 1st and 3rd Battalions are just bunking down for the night at their camp at Maidos, some six miles to the south-east. The men, under the vigilant eye of their Regiment Commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Åefik, have finally finished their long march back from Gaba Tepe.

Spent, they soon fall into the sleep of the dead and the dead exhausted.

2.30 AM, 25 APRIL 1915, OFF THE DARDANELLES, LIKE AN ARROW IN THE NIGHT

Slowly, oh so carefully, the

AE2

â after leaving HMS

Swiftsure

, which has been towing it â powers along on the surface into the jaws of hell, represented by the entrance to the Dardanelles Strait. The sea is as cold, flat and dark as black glass, the only ripples upon it forming a perfectly symmetrical and sparkling phosphorescent arrow in the moonlight, with the bulbous black bow of the

AE2

at its tip.

Ahead, searchlights from the shore criss-cross the waters. For the moment,

AE2

sticks closely to the European side of the Straits, slip-slip-slipping along at just a little over three knots, hoping to keep engine noise to a minimum and to stay away from those searchlights for as long as possible.

For all that, so strong is the moonlight, it seems scarcely believable that every fort on the Dardanelles is not there and then a hive of activity, bringing their guns to bear on

AE2

. âEach time,' Stoker would recount, âas a beam of light touched the

AE2

with brighter and yet brighter finger, one held for the instant one's breath, lest the steady sweep, arrested for a moment, would show a suspicion of our shadowy presence.'

28

That thumping?