Gallipoli (51 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

Godley refuses to move until Ellis does up his puttee. Then, just as he is about to go, he suddenly puts his hand to his cap and chuckles. A bullet has split it. âThat was a pretty near thing,' he laughs.

68

In all the madness of the battle, of death and devastation happening all around, one man in particular stands out. It is Simpson, and he is â can you believe it? â using a donkey to ferry the wounded from the frontlines back to the dressing stations, frequently under fire.

Just where he got the small donkey is never quite clear, only that he loves it, and the trusting donkey seems to love him. Simpson leads the donkey up to the highest part of Monash Valley, whereupon he would âleave the mule just under the brow of the hill and dash forward himself to the firing-line to save the wounded'.

69

The work of Simpson and his donkey is outstanding enough to be mentioned in despatches âfor conspicuous gallantry'. Colonel Monash himself would write of the duo, âThey worked all day and night ⦠and the help rendered to the wounded was invaluable. Simpson knew no fear, and moved unconcernedly amid shrapnel and rifle-fire, steadily carrying out his self-imposed task day by day, and he frequently earned the applause of the personnel for his many fearless rescues of wounded men from areas subject to rifle and shrapnel-fire.'

70

As a young lad growing up in South Shields in the far north of England, Simpson had worked at Murphy's Fair â hence his sometime nickname among the men of âMurphy', just as his donkey is variously known as Murphy or Duffy, to keep things confusing

71

â giving donkey rides to children for a penny a pop from sun-up to sundown, and his touch with the donkeys is sure because of it. As the only place to find fodder in these climes is with the 21st Kohat Indian Mountain Artillery Battery, who have brought many bales for their own mules, there to haul the big guns of the hills, that is where Simpson makes his base at night. He is substantially left to his own devices. The Indians call him â

Bahadur

', meaning âbrave'.

72

Having become separated from his own AMC unit, he has simply taken it upon himself to proceed on a roving commission regardless, and so obviously valuable is his work that no officer tries to intervene or re-establish control. The result, in the words of one soldier, is that Simpson is âthe only man on the peninsula ⦠under no one's immediate command'.

73

But never have Simpson and his donkey been so busy as on this night. The battle goes on and the 4th Brigade continues to push forward, despite it all.

Picking his way among his wounded and dead comrades, Ellis Silas looks up to see Sergeant David Caldwell, badly wounded but still full of spirit, coming down the other way.

âMy!' he says cheerfully, âbut they're willing up there.'

And here now is another man, a mate, waving a bloody stump where his right hand used to be.

âGod, but I've done my duty,' he calls sadly. âIs that you, Silas, old chap; I've done my duty, haven't I?'

74

Yes, mate, you've done your duty.

But there is little time to care for him. For now, with all the rest, Signalman Ellis Silas endeavours to keep going, while the next wave into battle start singing âTipperary' and âAustralia Will Be There':

Have no cause for fear!

Should old acquaintance be forgot?

No! No! No! No!

Australia will be there!

Australia will be there!

75

Against all odds, the 16th Battalion manages to get into the first trench five yards from the crest of the Bloody Angle and use their bayonets to clear it of Turks.

What is most desperately needed now is

support

, so they can hold onto this new, hard-won position.

Where, oh where, are the New Zealanders who are meant to be attacking the Turks from the flanks to take the pressure off the Australians?

Not even at their starting line. It is the worst of all possible outcomes, for not only are the New Zealanders unable to assist their Australian comrades, but now the whole of the higher reaches of Baby 700 is spitting death at all who approach. Any chance of reaching their objective has disappeared.

And now the clearing stations are receiving the first of the grievously wounded, a bloody flow that simply does not stop.

âThey kept coming just like the first day,' the diary of Lieutenant-Colonel Dr John Corbin would record. âDreadfully wounded and mangled, arms and legs shattered, heads crushed in, chests and abdomens, a most hateful procession ⦠No chance of giving anaesthetics ⦠view to get them to the ships without delay. The men today are more badly injured and all are in a fearful state of dirt, sand, dried blood, caked and smelly ⦠truly this is a dreadful war ⦠more like wholesale murder.'

76

Some one and a half hours after they had been meant to get there, the Otagos finally arrive, and yet they've no sooner come over the lip of the ridge than they are confronted by terrible fire from the Turks on Baby 700. No fewer than half of the brave Otagos are either killed or wounded.

None of this is known to General Godley, who has retreated to his own well-protected dugout some 500 yards away. From there, he decides the time is right to have a company of soldiers from the Canterbury Battalion attack across the Nek. The result: 46 soldiers and two officers killed.

In the valley below Baby 700, in a moment of rare respite after near-continuous battling since the landing, Captain Gordon Carter tries to grab some precious rest.

âThe rattle of musketry was deafening and continued all night,' he records. âI felt very anxious and could not sleep much â sometimes our rifles seem to have ascendancy and sometimes theirs.'

77

Idly, he wonders what Nurse King is doing, if she is safe.

And she is, broadly, albeit in appalling conditions.

Offshore, her hospital ship SS

Sicilia

is now full to cracking, and she finds herself tending to no fewer than 250 patients with the help of one Australian orderly and an Indian sweeper as the flickering lanterns throw a ghostly light over 1915's answer to Dante's

Inferno

.

âI shall never forget the awful feeling of hopelessness on night duty,' she would record. âIt was dreadful ⦠Shall not describe the wounds, they were too awful â¦

âNight duty is rather weird â going around in the dark and peering at everyone, not switching on the light unless absolutely necessary and doing the dressings here and there that were very necessary and then hearing someone groan or call “Nurse!” Some of the boys were delightful â dying to get well and go back to “get their own back”, as they say.'

78

The Australians of the 4th Brigade who have secured the most advanced trench manage to hold on through the long night against sustained Turkish counter-attacks, and maybe could continue to hold it. But in the first place, no reinforcements reach them, and secondly, just after 5 am by terrible mistake the Allied artillery opens up and the shells land on the very trench the Australians are holding.

The whole attack is a shambles. Not even able to hold onto the ground they have won, the Australians are forced to retreat, and they find themselves back where they started less than 24 hours earlier â less 338 of their number, who now lie in eternity. The New Zealanders have had 262 killed.

On 3 May, accompanied by Major Thomas Blamey, Charles Bean makes his way towards where the battle has taken place. And what Bean sees appals him, for there are

hundreds

of Australian dead.

âThe whole face of the cliff of the nearer hill which yesterday was covered with bushes is today bare, and along the top of it our dead can be seen lying like ants, shrivelled up or curled up, some still hugging their rifles, about a dozen of them. The face of the further plateau is also edged with our dead.'

79

Under the circumstances, he is not surprised to find Monash in his dugout, far from his normal self.

âThey've tried,' Monash says morosely, âto put the work of an Army Corps on me.'

80

From a starting turnout of some 3600 for his 4th Brigade, Colonel Monash now has just 1770 men capable of picking up a rifle and fighting.

âMonash seemed to me a little shaken,' Bean would confide to his diary that night. âHe was talking of “disaster”.'

81

No doubt.

âThe Snipers', by Ellis Silas (AWM ART90804)

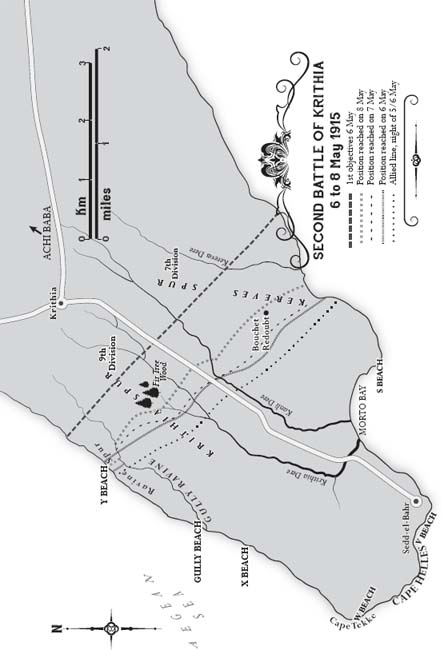

Second Battle of Krithia, by Jane Macaulay

6 MAY 1915, THE SECOND BATTLE OF KRITHIA TAKES PLACE

Though a naturally sunny soul, General Ian Hamilton is becoming desperate. Coming up to two weeks since the landing, his troops are pinned down at both Anzac Cove and Cape Helles. The two forces are not even close to joining up, and none of the strategic objectives designated for the first day has yet been achieved. Most particularly, the high ground of Achi Baba, seven miles inland from Cape Helles, is now defended by heavily entrenched Ottoman forces. That objective remains three and a half miles distant, and it has taken several thousand British and French lives to achieve even that.

But hopefully, on this morning, there will be a breakout at Cape Helles. Under the command of General Aylmer Hunter-Weston, the Empire's forces will once again attack Achi Baba, but this time,

this time

, his brigade of the 42nd Division will be bolstered by an Indian Brigade, together with the 2nd Australian Brigade and the New Zealand Infantry Brigade â the two brigades that remain the most intact after the landing and subsequent fighting. They have been brought over from Anzac, now that the situation there has become at least a little more stable. He will have 25,000 soldiers in all.

At Hunter-Weston's insistence, his forces will begin their attack at 11 am â a curious hour, given the enemy will see them from the first â with the aim of being in possession of the town of Krithia by mid-afternoon and in control of the whole hill of Achi Baba by dusk. Just why the result this time should be any less disastrous than last time he does not explain, and though General Hamilton has

grave

misgivings ⦠he feels he must let his old friend Hunter-Weston have his head, what?

Even though Hunter-Weston and his senior staff still have no idea how many defenders there are, where their artillery is situated and even where the Turks are concentrated, the principle is to jolly well allow the Commander to run his own show, and so General Hamilton does.

General Hunter-Weston, however, has few fears. That morning, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett visits with him in his bombproof shelter near Lancashire Landing, and the General is kind enough to show the journalist his plans, pointing out the enemy's position on maps and detailing what he and his troops intend to do.

Yes, despite the disasters so far, the General is bubbling over with confidence. âWe will take Krithia this afternoon,' General Hunter-Weston says firmly, âand possibly Achi Baba. But if there was no time for both, I will ensure we take Achi Baba tomorrow.'

82

The English correspondent, however, notes in his diary, âI quite fail to see on what his optimism is based.'

83

And so it begins, shortly afterwards, with Ashmead-Bartlett watching closely, amazed to be able to witness the battle in its entirety across the substantially open fields that lead to the slopes of Achi Baba, where the Turks are dug in.

âThe whole scene,' he would record, âresembled rather an old-fashioned field day at Aldershot than a modern battle. The Commander-in-Chief had, in fact, his troops under his eye, just as Wellington and Napoleon had them at Waterloo.'

84