Gallipoli (53 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

To his amazement, Bean finds himself loping forward in the prow of the attack, near Colonel McCay and some of his senior staff, together with half a dozen signallers. As they are tramping heavily up through the incline's low gorse bushes, the fire becomes so intense that one young Australian soldier on Bean's left holds his shovel up in front of his face.

A trench filled with the Lancashire Fusiliers â them again! â appears in front of the Australians, providing a place for a quick breather before the word comes once more: push forward!

Suddenly Bean sees a young man who has been shot just 20 yards or so in front of him, trying to crawl back. As soon as he makes to go out and save him, McCay orders him to stop. âI must,' Bean replies,

21

his voice filled with Victorian virtue, before rushing forward and, with difficulty as great as the danger, dragging the soldier back to relative safety.

âLook here, Bean, if you do any more of these damn fool actions,' McCay roars, âI'll send you straight back to Headquarters.'

22

Still, perhaps it has inspired the Colonel, too â that this thin, bespectacled and completely unsoldierly man has done such a heroic thing â for now, with a rueful smile, Colonel McCay says, âWell, Bean, this is where I suppose I have to do the damned heroic act.'

23

âNow then, Australians!' McCay yells to his soldiers as, clutching his revolver, he hurtles up and over the parapet like a man 20 years his junior. âWhich of you men are Australians? Come on, Australians!'

24

The Turkish defenders draw beads on them from their well-established trenches 600 yards ahead and unleash such a fusillade of fury that the first ranks out are quickly cut to pieces. No matter, the next formation charges forward, and then another and then another. Each time they charge forward, the cry of âCome on, Australians!' rings out.

âIt was great to watch them as they went,' Bean would recount, âabsolutely unaffected by bullets ⦠Their faces were set, their eyebrows bent, and they looked into it for a moment as men would into a dazzling flame. I never saw so many determined faces at once.'

25

On the left, men of the 29th Division are soon pinned down and able to progress no further than 200 yards from their starting point. And, of course, they too are decimated, just as they had been on the first day of the landing when, as Ashmead-Bartlett would recount, General Hunter-Weston had told them that âthey must occupy Achi Baba at all costs that afternoon. Apparently he left the Turks out of his calculations.'

26

The New Zealanders fare a little better as they are sent over broken ground that offers some cover. Yet, after taking one Turkish trench with bayonets, their advance too is halted by such heavy enfilading fire and shrapnel overhead that they are â exactly as Colonel Malone knew they would be, DAMMIT â torn apart, and the survivors must dig in.

General Hamilton, observing from a safe spot between W and X Beaches, would later record that âa young wounded Officer of the 29th Division said it was worth ten years of tennis to see the Australians and New Zealanders go in'.

27

No matter their bravery, there can only be one result: death and devastation. All the survivors can do, like the others, is go to ground less than 1000 yards ahead of their starting point.

All that Hamilton can do as the sun falls is send a message to his men to dig in where they now find themselves, and hope that they will be able to hold off the counter-attacks, which will inevitably come.

Most devastated are the Senegalese, the French colonial troops. Referred to by General Hamilton as âniggy wigs' and âgolly wogs',

28

they are the Allies' equivalent of the Arab regiments fighting for the Ottoman Empire. There by force not faith, they are possessed of fear not fight, and on this occasion they have to be practically lashed into position by officers of the French Foreign Legion pointing machine-guns and flashing their bayonets at them from behind. Their blue uniforms, too, shine brightly in the sun, and the terrified Africans go forward to the inevitable result.

âThey were getting mowed,' one Digger, Bill Greer, would recall years later. âThey were mowing them down. I never saw such slaughter. That was the native troops. The French couldn't care less.'

29

When darkness falls and the battle at last ebbs, Bean follows the signalling wire forward, in search of McCay. Passing many dead and dying men on the way, after 200 yards he does indeed find the Colonel alive in a forward trench â along with one lone signaller. Though glad to see him, McCay again calls the journalist a âfool!!!' â the pointed pertinence of those exclamation marks being provided by the three bullets that snap past Bean's ears at the time â before adding sadly, âThey set us an impossible task.'

30

The soldiers of Victoria's 2nd Brigade â Fitzroy, Euroa and Yarrawonga's finest sons â have been slaughtered. Of 2500 soldiers, 182 are dead, 539 wounded and 335 missing â over 1000 casualties in less than an hour â likely blown to bits with nary a body to bury. The New Zealanders have lost a third of their number, with 120 killed, 517 wounded and 134 missing â the last of whom, experience had tragically proven, would soon be found to be dead. As to the 29th Division, they have lost 1500 soldiers on the day, while the French have lost 812, most falling in front of a single Turkish trench.

In the course of three days, Hunter-Weston's forces have suffered 6200 casualties, three times more than the Turks. And for what? Not even 950 yards of ground.

Disappointed, Hamilton has dinner with his senior officers aboard

Arcadian

. What to do next? How to crack this Turkish nut that does not appear to want to be cracked? No one â least of all Hamilton â is quite sure. Nothing has worked so far.

Pass the port, there's a chap.

On the lower slopes of Achi Baba, hundreds of grievously wounded men lie among the dead, waiting, waiting, waiting for succour that never seems to come.

Charles Bean â having once again judged his duty to help save lives as higher than his duty to merely chronicle events â is nothing if not busy. Moving around in the darkness at considerable personal risk, he assists in guiding what few stretcher-bearers there are to where they are most needed, and ferries water back and forth to the lips of men whose very souls are crying out for it. There are

hundreds

of them, all around, crying for help, for doctors, for their mothers. Out of the night, a feeble voice is heard, asking for a stretcher-bearer.

âYou won't see them tonight, my boy,' comes a rather cheerful reply from a passing messenger from HQ, âthey're rarer than gold.'

There is a wounded pause, and then the faint voice from the dark comes back: âYou might let us think we will.'

31

Bean keeps moving among the men, doling out the water and making each can he carries go as far as possible by asking each man not to have too much. âEach fellow took about two sips and then handed it back,' Bean would faithfully record. âReally you could have cried to see how unselfish they were â¦'

32

At one point, encountering a signaller shot through the stomach and groaning in agony, he reaches for the two tablets of morphia his brother Jack had given him in case of emergency.

âWe are now on our last legs,' Hamilton records in his diary. âThe beautiful Battalions of the 25th April are wasted skeletons now; shadows of what they had been. The thought of the river of blood, against which I painfully made my way when I met these multitudes of wounded coming down to the shore, was unnerving. But every soldier has to fight down these pitiful sensations: the enemy may be harder hit than he: if we do not push them further back the beaches will become untenable. To overdrive the willingest troops any General ever had under his command is a sin â but we must go on fighting to-morrow!'

33

As to General Hunter-Weston, while it might be expected that he would be equally downcast at what has happened ⦠not a bit of it. At a later point in the campaign, when he would be asked how many casualties he had suffered, his answer would come close to defining the âButcher of Cape Helles', as he would also become known. âCasualties?' Hunter-Weston snaps. âWhat do I care about casualties?'

34

In the here and now, nigh everyone else does care, however. âFor the first time,' Ashmead-Bartlett records, âan atmosphere of depression settled over the army at Cape Helles. Up to the evening of May 8th there still remained a slight ray of hope in the minds of the men that something definite might yet be accomplished. Now that hope had fled.'

35

Far from the Allies being able to take Krithia or Achi Baba, things for them are now so bad that, as the disgusted Ashmead-Bartlett notes, it is ânecessary to construct a defensive line to hold off the Turkish counter-attacks until reinforcements could arrive'.

36

For the whole day after the battle, Ashmead-Bartlett remains on board

Implacable

trying to compose a cable that will capture the events of the last three days. And yet â¦

âIt is,' as he would confide to his diary, âheartrending work having to write what I know to be untrue, and in the end having to confine myself to giving a descriptive account of the useless slaughter of thousands of my fellow countrymen for the benefit of the public at home, when what I wish to do is to tell the world the blunders that are being daily committed on this blood-stained Peninsula. Yet I am helpless. Any word of criticism will be eliminated by the censor â¦'

37

For the moment, however, all he can do is write something that

will

pass the censor.

9 MAY 1915, AUBERS RIDGE, HELL IN ONE DAY

Alas, things are no better on the Western Front, where on this day the forces of Sir John French launch a mass attack on heavily entrenched German positions at Aubers Ridge, in the far north of France. Using defective intelligence and a complete lack of surprise, against a numerically superior force who are armed to the teeth and with enough ammunition stockpiled to sink a battleship, the results are nothing short of catastrophic, with Great Britain suffering 11,000 casualties on this

single day.

Who is to take the blame? Sir John himself is convinced that it lies with his masters in London, who had not supplied him with sufficient high-explosive shells of the right type, capable of destroying the German machine-gun positions, barbed-wire entanglements and fortifications before the British advance. His anger is exacerbated when, only shortly after the battle is over, he is told he must send no fewer than 20,000 shells straight to Marseilles, where fast ships are waiting to take them on to the Dardanelles, for use in

their

campaign.

In London, when he hears of it in his spacious and elegantly appointed office in Fleet Street's Carmelite House, Lord Northcliffe can stand it no longer. More than not having an adequate supply of the right kind of shells, it is obvious to him that Britain has the wrong kind of

leaders

⦠The Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, and the Secretary for War, Lord Kitchener, are simply not up to it. And as for Winston Churchill, he is the one responsible for the Dardanelles debacle draining much needed munitions from France.

Something must be done, and Lord Northcliffe is just the man to do it.

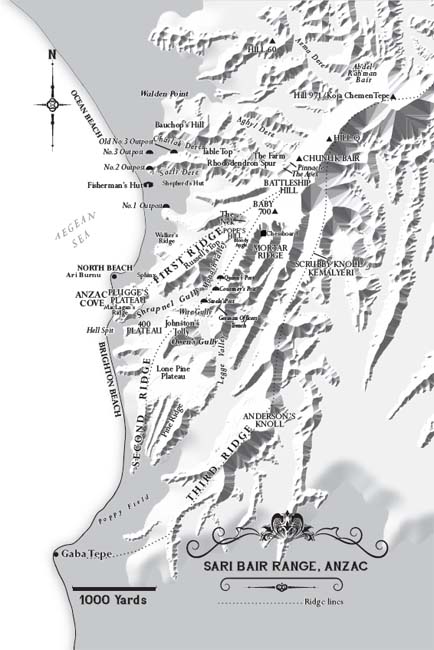

Sari Bair Range, by Jane Macaulay

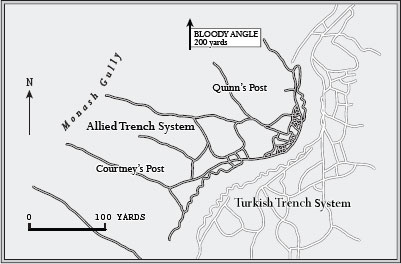

Quinn's PostâCourtney's Post trench system, by Jane Macaulay

EVENING, 9 MAY 1915, HOLDING ON AT QUINN'S POST, âTHE HOTTEST CORNER OF GALLIPOLI'

38