Goodbye, Darkness (44 page)

Later, after the First Marines had suffered over seventeen hundred casualties, another naval officer asked an evacuated Marine if he had any souvenirs to trade. The Marine stared at him and then reached down and patted his butt. “I brought my ass out of there, swabbie,” he said. “That's my souvenir of Peleliu.” Painfully aware that they continued to carry prewar equipment, priority still being given to the ETO, and learning that the bombardment had been entrusted to inexperienced naval commanders, the men who suffered on this ill-starred island became bitter. A Marine officer later said: “It seemed to us that somebody forgot to give the order to call off Peleliu. That's one place nobody wants to remember.” Oldendorf conceded that if Nimitz had realized the implications of his decision, “undoubtedly the assault and capture of the Palaus would never have been attempted.”

Time

called it “a horrible place.” Few Americans at home even knew of the ferocious struggle there. When President Truman pinned a medal on a Peleliu hero, he couldn't pronounce the island's name. Samuel Eliot Morison, rarely critical of U.S. admirals, wrote that “Stalemate II,” as the operation had been prophetically encoded, “should have been counter-manded,” being “hardly worth” the price of over ten thousand American casualties — three times Tarawa's.

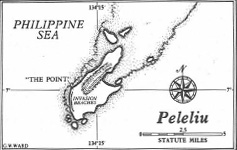

The target island, seven miles long and two miles wide, lies within the coral reef which surrounds most of the Palaus. Peleliu is shaped like a lobster's claw. The Jap airstrip had been built on a level field south of the claw's hinge. North of the hinge a spiny ridge of rock dominates the battlefield. Steep, heavily forested, and riddled with caves, it was known as the Umurbrogol until the Marines rechristened it Bloody Nose Ridge. The enemy knew that any assault on the Palaus would have to hit Peleliu's mushy white sand coast because the airfield was there, and because the reef there was closest to the shore. The island's postwar population is about four hundred. In the summer of 1944, over twelve hundred natives had been living here. Most of them left before the battle because U.S. planes, in one of those humane gestures which fighting men will never understand, had showered Peleliu with leaflets warning of the coming attack. Undoubtedly that saved the lives of many islanders, but it cost American lives, too, because the Japanese also read the pamphlets and made their dispositions accordingly.

It was the misfortune of the attackers — the First Marine Division, followed by the Eighty-first Army Division — that their landings coincided with a revolutionary change in Japanese tactics. The murderous doctrine of attrition, which had first appeared as a local commander's decision on Biak, and which would reach its peak in the slaughterhouses of Iwo Jima and Okinawa, became official enemy policy in the weeks before the Battle of Peleliu. There would be no more banzai charges. Tokyo knew the war was lost. The Japanese garrisons in the Palaus were written off; their orders were to butcher Marines and GIs, bleeding them white before falling themselves — to dig deep, hold their fire during bombardments and preliminary maneuvering, and infiltrate and counterattack whenever possible. Thus the Peleliu gunports with sliding steel doors; thus the blasting of more than five hundred cunningly located coral caverns, one of them large enough to hold a thousand Japs, well stocked with food and ammunition. Most of the caves were tiered, with laterals, bays, and alternate entrances. Some were six stories deep, with slanting, labyrinthine entrances to deflect flamethrower jets and satchel charges of TNT. Camouflaged so that Americans would unwittingly advance beyond them, these fortresses held Nips drilled to emerge and attack from the rear following seven separate counterattack plans, each to be triggered by a signal flag or flare. On September 14, 1944, there were 10,700 such Japanese waiting, all prepared to die, all aware that the survivors among them would make their last stand on Bloody Nose Ridge. The terrain was their ally. Mangrove swamps, inside the reef, encircled the entire island. Steep-sided ravines — often more like chasms between cliffs — made progress difficult. Finding the fire zones of pillboxes and caverns would be even harder.

This, then, was the ghastly stage which awaited three regiments, veterans of Guadalcanal, who had been recuperating in the Solomons. They landed abreast: Puller's First Marines on the left, the Fifth Marines in the center, and the Seventh Marines on the right. The instant they reached the reef it burst, as Saipan's had, in a sheet of fire, steel, and lead. Only the Fifth landed more or less intact, threw a loop over the southern runways on the airfield, and, crossing the island, anchored on the far shore by evening. For the other regiments the landing was Tarawa without a seawall. To the right of the Seventh, obstacles which had eluded the frogmen marooned blazing amphtracs on the reef and forced the rest to come in single file, each in succession a lonely target, so that Marines jumped off and waded in instead. But the First Marines, moving under the muzzles of the largest pillboxes, faced the hardest task of all. Those who reached the beach were trapped by enfilading fire from the Point. One company was down to eighteen men. In a coconut grove near the water's edge the dead and dying, furled in bloody bandages, lay row on row, the corpses grotesquely transfixed in attitudes of death and those still alive writhing and groaning. Ahead, in craggy jungle laced with enemy machine-gun nests, lay knobs and wrinkles of stone which, as the riflemen approached them, were christened Death Valley, the Horseshoe, the Five Sisters, the Five Brothers, and Walt Ridge.

At 5:30

p.m

. of the first day, the Japanese counterattacked across the airfield from a wrecked hangar, led by thirteen light tanks. With Nip infantry clinging to them at every possible place, the tanks raced, their throttles open, like charging cavalry. The Marines fired back with everything they had: bazookas, 37-millimeter antitank guns, pack howitzers, Sherman tanks armed with 75-millimeter guns, and, at the moment of collision between the two forces, a well-timed lunge by an American dive-bomber. One man rushed a Jap tank with his flamethrower and was cut down when a burst of machine-gun fire ripped open his chest. Marine infantry held fast; several Nip tanks reached our lines, prodding with their grotesque snouts, but their skin of armor was too thin to withstand the concentrated fire, and Marines standing in full view of their gunners, some even perched on rocks, blazed away until the last tank blew up.

Digging foxholes on Peleliu, as on so many islands, was impossible. Beneath the dense scrub jungle lay solid limestone and coral. At midnight the Japanese opened fire with heavy mortars; then their infiltrating parties crept close to Marine outposts. The cruiser

Honolulu

and three destroyers sent up star shells, exposing the infiltrators to our small-arms fire. Fire discipline had to be tight; amphtracs were bringing in ammunition as quickly as possible, but some units ran out of it; one company commander led his men in throwing chunks of coral at the Nips. Sniper fire, the scuffling of crawling Japs, and the wounded's cries for corpsmen continued until dawn, when the enemy mounted new mortar and grenade barrages. Marine radios had been knocked out and were useless for calling in supporting fire from our artillery and mortars, and some companies had lost two men out of every three, but the American lines held fast and the airfield was seized by the Fifth Marines. With the Seventh Marines driving south, the first assault on Bloody Nose Ridge fell to Puller's regiment, which had already suffered the heaviest losses in the attacking force.

They confronted an utterly barren land. Naval gunfire had denuded the Umurbrogol, leaving naked mazes of gulches, crags, and pocked rubble which became coral shrapnel as the enemy artillerymen found their range. The sharp rock underfoot sliced open men's boondockers and, when they hit the deck as incoming shells arrived, tore their flesh. They mounted the first scarp and found another, higher, rising beyond it; thirty-five caves had to be blown up before they could advance further. Then a ferocious counterattack threw them back. This went on, dawn to dusk, with hand-to-hand struggles in the dark, until, on the sixth day, the First Marines' three companies, 612 men, had been reduced to 74. Platoons of the Seventh Marines were fed into the lines and immediately pinned down. GIs of the Eighty-first Division arrived while the Fifth Marines attacked the Umurbrogol from the north. Everyone was waiting for the banzai charge which had ended other battles. Slowly they grasped the enemy's new tactics. A Marine company would scale a bluff unmolested; then the Japanese would open up on three sides with infantry fire, mortars, and antitank guns, killing the Americans or throwing them to their death on the floor of the gorge below.

The Ridge had become a monstrous thing. Wounded men lay on shelves of rock, moaning or screaming as they were hit again and again. Their comrades fell and tumbled past them. Some men committed the ultimate sin for Marines, throwing away their rifles and clawing back down the slopes. Down below, a shocked company commander yelled, “Smoke up that hill!” Under roiling clouds from smoke grenades, those not hit tried to lead or carry the wounded down. One infantryman, bleeding badly, cried, “You've done all you could for us. Get out of here!” The company commander ran up, carried one casualty down, and laid him in defilade beside a tank hulk. As he straightened, a mortar shell killed him. His exec, a second lieutenant, sprinted up to help; he was killed by an antitank shell. The company was down to eleven men, finished as a fighting unit.

Bloody Nose Ridge, 1978

Now the slow, horrible slugging of attrition began. Hummocks of shattered coral changed hands again and again. Cave entrances were sealed with TNT; the Japs within escaped through tunnels. Corsair fighters dove at pillboxes; their bombs exploded harmlessly. Tongues of wicked fire licked at Nip strongpoints from flamethrowers mounted on Shermans; Japs appeared in ravines and knocked the Shermans out with grenades. Using the airfield was impossible; cave entrances overlooked it. Slowly, moving upward in searing heat — the thermometer seemed stuck at 115 degrees in the shade — Marines rooted out enemy troops or sealed them off, hole by hole. The island was declared secure on September 30, but eight weeks of desperate fighting lay ahead. By the end of October, when GIs arrived in force, the defenders had been reduced to about seven hundred men. The Japanese commander burned his flag and committed hara-kiri. Yet two months later Japs were still killing GIs poking around for souvenirs. The last of the Japs did not surface until eleven years later.

We used to say that the Japanese fought for their emperor, the British for glory, and the Americans for souvenirs. One wonders how many attics in the United States are cluttered with samurai swords and Rising Sun flags, keepsakes that once seemed so valuable and are worthless today. I collected them like everyone else, but I shall never understand men whose jobs kept them away from the front, who could safely wait out the war — “sweat it out,” as we said then — yet who deliberately courted death in those Golcondas of mementos, the combat zones. You heard stories about “Remington Raiders,” “chairborne” men ready to risk everything for something,

anything,

that would impress families and girls at home. I didn't believe any of them until I saw one. Even then I wondered what he was looking for. I suppose he was partly moved by a need to prove something to himself. He succeeded.

Our war, unlike our fathers', was largely mobile. It was just as bloody and, because of such technological achievements as napalm and flamethrowers, at least as ugly, but we didn't live troglodytic lives in trenches facing no-man's-land, where the same stumps, splintered to matchwood, stood in silhouette against the sky day after desolate day, and great victories were measured by gains of a few hundred yards of sour ground. Nevertheless, there were battles — Bloody Nose Ridge was one — where we were trapped in static warfare, neither side able to move, both ravaged around the clock by massed enemy fire. I saw similar deadlocks, most memorably at Takargshi. It wasn't worse than war of movement, but it was different. Under such circumstances the instinct of self-preservation turns the skilled infantryman into a mole, a ferret, or a cheetah, depending on the clear and present danger of the moment. He will do anything to avoid drawing enemy fire, or, having drawn it, to reach defilade as swiftly as possible. A scout, which is essentially what I was, learned to know the landscape down to the last hollow and stone as thoroughly as a child knows his backyard or a pet a small park. In such a situation, certain topographical features, insignificant under any other circumstances, become obsessions. At Takargshi they were known as Dead Man's Corner, Krank's Chancre, the Hanging Tree, the Double Asshole, and the End Zone. It was in the End Zone that I met the souvenir hunter. We were introduced by a Japanese 6.5-millimeter light machine gun, a gas-operated, hopper-fed weapon with a muzzle velocity of 2,440 feet per second which fired 150 rounds a minute in 5-round bursts. Its effective range was 1,640 yards. We were both well within that.