Goodbye, Darkness (45 page)

At Takargshi, as so often elsewhere, I was carrying a message to the battalion operations officer. All morning I had been hanging around Dog Company CP, content to lie back on the oars after a patrol, but the company commander wanted heavy mortar support and he couldn't get through to battalion. The Japs had jammed the radio; all you heard was martial music. So I was drafted as a runner. If there had been any way to shirk it I would have. There was only one approach from here to battalion. I had come up it this morning, at dawn. The risk then had been acceptable. The light was faint and the rifles of the section covered me on the first leg, the one dangerous place. Now, however, the daylight was broad, and since I wasn't expected back until dusk, I couldn't count on covering fire from anybody. Still, I had no choice, so I went. I remember the moment I took off from the Dog CP. The stench of cordite was heavy. I was hot and thirsty. And I felt that premonition of danger which is ludicrous to everyone except those who have experienced it and lived to tell of it. All my senses were exceptionally alert. A bristling, tingling feeling raced up my back. Each decision to move was made with great deliberation and then executed as rapidly as a Jesse Owens sprint. I had that sensation you have when you think someone is looking at you, and you turn around, and you are right. So I made the ninety-degree turn at Dead Man's Corner, stealthily, dodged past Krank's Chancre, burrowed through the exposed roots of the Hanging Tree, bounded over the Double Asshole — two shell holes — and lay in defilade, gasping and sweating, trying not to panic at the thought of what came next. What came next was the End Zone, a broad ledge about thirty yards long, all of it naked to enemy gunners. Even with covering fire three men had been killed and five wounded trying to cross the Zone. But many more had made it safely, and I kept reminding myself of that as I counted to ten and then leapt out like a whippet, my legs pumping, picking up momentum, flying toward the sheltering rock beyond.

On the third pump I heard the machine gun, humming close like a swarm of enveloping bees. Then several things happened at once. Coming from the opposite direction, a uniformed figure with a bare GI steel helmet emerged hesitantly from the rock toward which I was rushing. Simultaneously, I hit the deck, rolled twice, advanced four pumps, dropped and rolled again, felt a sharp blow just above my right kneecap, dropped and rolled twice more, passing the shifting figure, and slid home, head first, reaching the haven of the rock. My chest was pounding and my right knee was bloody and my mouth had a bitter taste. On my second gulp of air I heard a thud behind me and a thin wail: “Medic!” My hand flew to my weapon. Infantrymen are professional paranoiacs. Wounded Marines call for corpsmen, not medics. As far as I knew, and it was my job to know such things, there wasn't supposed to be a GI within a mile of here. But as I rose I saw, crawling toward me, a wailing, badly hit soldier of the U.S. Army. His blouse around his stomach was bellying with blood. And he wasn't safe yet. Just before he reached the sanctuary of the rock, a 6.5-millimeter burst ripped away the left half of his jaw. I reached out, grabbed his wrist, and yanked him out of the Zone. Then I turned him on his back. Blood was seeping through his abdomen and streaming from his mangled chin. First aid would have been pointless. I wasn't a corpsman; I had no morphine; I couldn't think what to do. I noticed the Jap colors sticking from one of those huge side pockets on his GI pants. It wasn't much of a flag: just a thin synthetic rectangle with a red blob on a white field; no streaming rays, no

kanji

inscriptions. We'd kept these thin, unmarked little banners earlier in the war and thrown them away when we found that the Japs had thousands of them, whole cases of them, in their supply dumps.

The GI looked up at me with spaniel eyes. One cheek was smudged with coral dust. The other was dead white. I asked him who he was, what he was doing here. Setting down his exact words is impossible. There is no way to reproduce the gargling sound, the wet sucking around his smashed jaw. Yet he did get out a few intelligible phrases. He was a Seventy-seventh Division quartermaster clerk, and he had been roaming around the line searching for “loot” to send his family. I felt revulsion, pity, and disgust. If this hadn't happened in battle — if, say, he had been injured at home in an automobile accident — I would have consoled him. But a foot soldier retains his sanity only by hardening himself. Though I could still cry, and did, I saved my tears for the men I knew. This GI was a stranger. His behavior had been suicidal and cheap. Everything I had learned about wounds told me his were mortal. I couldn't just leave him here, but I was raging inside, not just at him but he was part of it, too.

The battalion aid station was a ten-minute walk away. This trip took longer. I had slung him over my shoulders in a fireman's carry, and he was much heavier than I was. My own slight wound, which had started to clot, began bleeding again. Once I had him up on my back and started trudging, he stopped trying to talk. I talked, though; I was swearing and ranting to myself. His blood was streaming down my back, warm at first and then sticky. I felt glued to him. I wondered whether they would have to cut us apart, whether I'd have to turn in my salty blouse for a new one, making me look like a replacement. I was wallowing in self-pity; all my thoughts were selfish; I knew he was suffering, but his agony found no echo in my heart now. I wanted to get rid of him. My eyes were damp, not from sorrow but because sweat was streaming from my brow. Apart from unfocused wrath, my strongest feeling was a heave of relief in my chest when I spotted the canvas tenting of the aid station on the reverse slope of a small bluff.

Two corpsmen ran out to help me. He and I

were

stuck to each other, or at least our uniforms were; there was a smacking sound as they swung him off me and laid him out. I turned and looked. His eyes had that blurry cast. There we were, the three of us, just staring down. Then one of the corpsmen turned to me. “A dogface,” he said. “How come?” I didn't know what to say. The truth was so preposterous that it would sound like a desecration. Fleetingly I wondered who would write his family, and how they would put it. How

could

you put it? “Dear folks: Your son was killed in action while stupidly heading for the Double Asshole in search of loot”? Even if you invented a story about heroism in combat, you wouldn't convince them. They must have known he was supposed to be back in QM. I avoided the corpsman's eyes and shrugged. It wasn't my problem. I gave a runner my message to the battalion CP. My wound had been salted with sulfa powder and dressed before I realized that I hadn't looked at the corpse's dog tags. I didn't even know who he had been.

Today Peleliu can be reached only from the Palauan island of Koror, itself no hub of activity, though powerful interests would like to make it one. Robert Owen, district administrator for the Trust Territory, tells the sad tale. Owen is one of those tireless American advisers who serve in the tropics much as Englishmen served a century ago: underpaid, overworked, and absolutely devoted to the islands. But after twenty-nine years here he has decided to quit. His whole career has been a struggle for Palauan ecology, and he has just about lost it. Fishermen smuggle in dynamite, devastating the waters; the streams are contaminated with Clorox; the topsoil, already thin, is vanishing because of inept use of chemicals that create erosion.

But the real rogues, in Owen's opinion, are a consortium of Japanese and Middle East petroleum titans, led by an American entrepreneur, who want to build a superport here to service supertankers. “The Japanese,” he says, “want to export their pollution.” Every supertanker eventually defiles the water around it — recently twenty-three hundred tons were spilled in French waters — and Owen predicts the end of the Palaus' delicate environment, the destruction of irreplaceable flora and fauna. The natives approve of superport plans because they think their standard of living will rise, but in Puerto Rico, he has tried to tell them, it was the wealthy, not the poor, who reaped the profits of a similar project. He is appealing to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which has the power to reject the plans. He doubts it will.

Although I am sympathetic, my contract is with the past and his with the future. We glide past one another like freighters flying the same flag of convenience but bound for very different destinations. Yet I know he is right; it would be tragic to lose the Palaus. That thought may startle those who fought here, who remember only the horror and the heat. In peacetime, however, the islands' aspect is altogether different, and you become aware of it long before you reach Peleliu. Checking in at the thatch-roofed hotel, you rent a Toyota Land Cruiser and drive to the ferry slip. The ferry — actually a small launch powered by twin 85-horsepower Johnsons — takes you past the breathtaking Rock Islands, which resemble enormous green toadstools, narrow at the bottom, because of erosion and sea urchins, and swelling into dark green caps of vegetation above. Some of the islands have natural caves. The Japanese used these for storage; deteriorating wooden boxes and corroded tin containers may still be found there, and one cavern, which was used to stockpile Nipponese ammunition, is black where an American demolitions team blew it up. These are great waters for snorkeling, clear and abundant with life. Tuna are thick, and so are mackerel, bonito, marlin, sailfish, and flying fish. But there are also sharks and barracuda, and, most menacing of all, giant tridacna clams, some four feet across, whose traverse adduction muscles can grip divers and carry them to a drowning death. Before the battle, the great clams were a special threat to navy frogmen, who carried long knives to cut the creatures' muscles.

Once you have reached Peleliu, you are on your own, unless, as in my case, you have a native acquaintance. My friend is Dave Ngirmidol, a short, swart, powerfully built history major from California State University in Northridge and now a Trust Territory employee. Dave is waiting for me at the island's only dock with a Mazda pickup truck and three islanders: Hinao Soalablai, the island's young magistrate; Ichiro Loitang, an elderly Papuan who ran the island after all the Japanese had been wiped out and before American Military Government arrived; and Kalista Smau, whose chief qualifications for this field trip are her beauty, her lovely smile, and the brightest green Punjabi trousers I have ever seen.

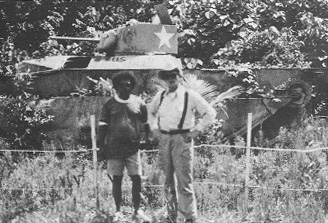

Dave Ngirmidol and the author alongside an abandoned American tank

Miss Smau also carries, in a basket balanced on her head, box lunches and raspberry-flavored soda. She offers a bottle, and I boorishly drain it. I am apologetic, but she is delighted; Dave explains that I have paid her a great compliment. So off we go in the little truck, bouncing over deeply rutted paths and ducking to avoid tremendous swooping branches. In Koror I asked a botanist to identify Palau foliage. He threw up his hands; thirty or forty major genera have been classified, he said, and they haven't been able to explore beyond the outermost fringes of the rainforests.

The road becomes a sticky, humid trough, but if I am uncomfortable, my companions are not; they are eager to tell me what the war did to Peleliu. Regrettably, they are not always reliable. Every great battle becomes a source of apocrypha. Near the water we come upon a small beached yacht, the

Por Dinana,

once white but now rusted, and my guides tell me it was General MacArthur's headquarters, which is a geographic impossibility; MacArthur was never within a hundred miles of Peleliu. Still, they know what they actually witnessed. For ages the islanders had lived in thatched A-frame huts, eating coconuts, pandanus fruit, breadfruit, and taros, starchy tubers much like potatoes. Then the Japanese, their ostensible protectors, rounded them up, put them in camps, and assigned them to forced labor. There was a lot to do; Peleliu was being heavily fortified. Importing coastal defense guns, the Japanese sited them so they could dominate Toagel Mlungui Strait, the narrow channel through which American battleships would have to pass. They overlooked air power, even when U.S. planes were overhead every day dropping their leaflets, telling the natives to get out while the getting was good.

One reason so few of the evacuees returned after V-J Day was the postwar craze — it still flourishes — of Modekne, a nativist religion preaching a return to prewar simplicity. Modekne's center was and is Koror, where natives dispossessed by the fighting put down roots. On Peleliu there were more corpses than people, and very little activity. The Americans disposed of their Higgins boats by sinking them and then departed — that is, most of them departed; when we reach the serene invasion beach, rimmed by Samoan palms and conifers, I find near it an imposing fence bearing a sign informing me that this is a “Federal Program Campsite — CITA Project No. VIII.” Dave explains that Americans are training islanders in new skills; he doesn't know which, and there is no one around to instruct us.

Trudging through the brush at the base of Bloody Nose Ridge, I find ten-inch Nip guns, oiled and ready for action. Who has been cleaning them? My companions seem as astonished as I am. The only possibility is the Japanese who arrive in the Palaus, as elsewhere, in large numbers, and who have erected two monuments to their dead. We speculate upon their motives and settle for the cliché that Orientals (the islanders do not regard themselves as Orientals) are inscrutable.