Goodbye, Darkness (48 page)

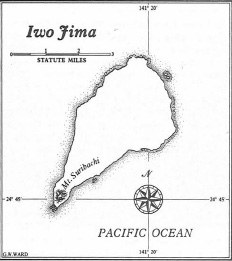

Once the Joint Chiefs had decided to retake the Philippines, instead of bypassing them, plans for driving toward Formosa or the Chinese mainland were discarded, to be replaced by a direct lunge at the Japanese home islands. Two more stepping-stones were needed: Iwo Jima, in the Volcano Islands, and Okinawa, in the Ryukyus. Iwo Jima was to be seized first, because it was considered easier — which was true, in the sense that Buchenwald was less lethal than Auschwitz — and because Iwo was a major obstacle for B-29 Superfortress fleets raiding Tokyo. The first Superfort attack on the Japanese capital had been staged from Saipan on November 24, 1944, but the results of the raids had been disappointing. Curtis LeMay, their commander, said, “This outfit has been getting a lot of publicity without having accomplished a hell of a lot in bombing results.” Iwo Jima was the chief reason. Situated halfway between the Marianas and Japan, Iwo's radar sets gave Tokyo two hours' warning of approaching B-29s. Zeroes based on the island swarmed around the big bombers both coming up from the Marianas and then returning, when they had often been crippled by flak. Moreover, the Japs flew some raids of their own on our Saipan, Tinian, and Guam bases. Therefore in mid-February, when the house-to-house fighting in Manila was reaching its height, convoys bearing the Third, Fourth, and Fifth Marine divisions steamed toward Iwo.

The cemetery at Makati

B-24s had been flying high-level sorties over the island for six weeks, but aerial photographs showed negligible results. Now U.S. warships approached Iwo like hunters stalking a maimed but still vicious tiger. They moved slowly and deliberately, trying to test the enemy's strength and at the same time lure him into action. To the U.S. fliers and naval gunners, Iwo appeared absurdly small prey. The island was just four miles long — altogether, eight square miles — an ugly, smelly glob of cold lava squatting in a surly ocean. In silhouette it was shaped somewhat like the Civil War ironclad

Monitor,

the “cheesebox on a raft,” the raft in this case being the northern mass of the island and the cheesebox, on the southwest tip, the volcanic crater of 556-foot Mount Suribachi,

Suribachi

being Japanese for “cone-shaped bowl.”

Iwo

is Japanese for “sulfur,” and daring pilots who swept low over its three airfields knew why; jets of green and yellow sulfuric mist penetrated the entire surface of the isle, giving it a permanent stench of rotten eggs. Essentially Iwo had changed little since it had risen, hissing, from the sea. Nipponese farmers had tried to grow sugar and pineapples there, with little success; by late 1944 they had given up and returned home. And yet Iwo in some ways seemed quintessentially Japanese. It had the tiny, fastidious compactness of small Tokyo backyards, and its rocks resembled the wind-buffed, water-scoured stones Nips love to collect for their miniature gardens. There the similarity to any civilized community ended, however. Most of the isle was a desolate, barren wasteland of volcanic pumice, finer than sand; more like coarse, loose flour. The only landing beaches were below Suribachi, to the immediate left and right of its base. North of there lay a smoking, blasted wilderness of crags, caves, buttes, and canyons, ending in jagged ridges overlooking the sea.

Samuel Eliot Morison wrote: “The operation looked like a pushover. Optimists predicted that the island would be secured in four days.” Some thought seventy-two hours would be enough. Here, as throughout the war, naval gunnery officers wildly exaggerated the effect of their preinvasion bombardment. One reported jubilantly that a fourteen-inch shell, scoring a direct hit in the mouth of a cave, destroyed a gun, leaving it to hang over the cliff below “like a half-extracted tooth hanging on a man's jaw.” But hundreds of other guns were intact. Holland Smith, warning that “we may expect casualties far beyond any heretofore suffered in the Central Pacific,” and estimating that we might lose fifteen thousand men — which was thought to be ridiculously high and proved to be ridiculously low — asked for a nine-day bombardment, like Guam's. The navy gave him three, explaining that they must depart to bombard the beaches of central Okinawa, where, ironically, there were no defenses. Our naval guns did rock Iwo Jima with more shells than those fired on Saipan, fifteen times as large as Iwo, but it wasn't enough, and even the frogmen, though now skilled and numerous, missed many underwater obstacles on Iwo. The fact is that nothing short of nuclear weapons could have left a serious dent in the enemy's defenses. Here, as in southern Okinawa, the new let-'em-come-to-us tactics approached perfection.

The defenders' CO, Tadamichi Kuribayashi — Holland Smith called him Hirohito's “most redoubtable” commander — had been among the first to conclude that banzai charges, once so effective in Japan's earlier wars with Russia and China, were futile against American firepower. Tokyo had warned him that he could expect no reinforcements. He replied that he didn't need them; the air attacks on Iwo had tipped off the coming invasion, and transports had beefed up his garrison to twenty-one thousand men, led by Japanese Marines. Kuribayashi turned his men into supermoles, excavating the hard

konhake

rock. They built 750 major defense installations sheltering guns, and blockhouses with five-foot concrete walls, strengthened, in some instances, with fifty feet of earthen cover overhead. Under Suribachi alone lay a four-story galley and a hospital cave. Southward from the volcano lay interweaving iron belts of defense. Altogether there were thirteen thousand yards of tunnels and five thousand cave entrances and pillboxes — a thousand on Suribachi alone. Once he learned of the force about to attack him, Kuribayashi had no illusion about his future. He wrote his wife: “Do not plan for my return.” Rear Admiral Toshinosuke Ichimaru, who led the seven thousand Nipponese Marines, felt the same way. Awaiting the coming assault, he wrote a poem:

Let me fall like a flower petal

May enemy bombs be directed at me, and enemy shells

Mark me their target.

Yet both the general and the admiral were burrowing in. They meant to make the conquest of Iwo so costly that the Americans would recoil from the thought of invading their homeland. They knew the island could be taken only by infantrymen; the U.S. warships' 21,926 shells and the six weeks of B-24 bombing didn't touch them; it merely rearranged the volcanic ash overhead and gave the invaders dangerous illusions of easy pickings. Those illusions were dashed on D-minus-2, when the Japanese mistook a deep reconnaissance by navy and Marine frogmen for the main landing; six-inchers embedded in the base of Suribachi and the face of a quarry to the north roared and quickly sank twelve small U.S. warships. So much for the high hopes. Everyone knew now that just as sure as God made little green Japs, the Higgins boats ferrying in the first Marine waves might as well be tumbrels.

On D-day Iwo seemed to lie low in the water, shrouded in dust and smoke. Two divisions were landed abreast, the Fifth's job being to knife across the isle's narrow neck and seize Suribachi while the Fourth turned northward. The moment they hit the shore they were in trouble. The steep-pitched beach sucked hundreds of men seaward in its backwash. Mines blew up Sherman tanks. Infantrymen found it impossible to dig foxholes in the powdery volcanic ash; the sides kept caving in. The invaders were taking heavy mortar and artillery fire. Steel sleeted down on them like the lash of a desert storm. By dusk 2,420 of the 30,000 men in the beachhead were dead or wounded. The perimeter was only four thousand yards long, seven hundred yards deep in the north and a thousand yards in the south. It resembled Doré's illustrations of the

Inferno.

Essential cargo — ammo, rations, water — was piled up in sprawling chaos. And gore, flesh, and bones were lying all about. The deaths on Iwo were extraordinarily violent. There seemed to be no clean wounds; just fragments of corpses. It reminded one battalion medical officer of a Bellevue dissecting room. Often the only way to distinguish between Japanese and Marine dead was by the legs; Marines wore canvas leggings and Nips khaki puttees. Otherwise identification was completely impossible. You tripped over strings of viscera fifteen feet long, over bodies which had been cut in half at the waist. Legs and arms, and heads bearing only necks, lay fifty feet from the closest torsos. As night fell the beachhead reeked with the stench of burning flesh. It was doubtful that a night counterattack by the Japs could be contained.

But there was none. Kuribayashi stuck to his battle plan, lying in wait. The next day the U.S. push northward began at an agonizingly slow pace and continued this, week after week, with heartbreaking engagements gaining as little as sixty or seventy yards a day. Curiously, the flag raising atop Mount Suribachi by the Twenty-eighth Marines, the most famous photograph of the Pacific war, was taken early in the struggle, on the fifth day of battle, before the Americans confronted the enormity of the challenge before them. Believing they had reached the first of their three main objectives — the others were conquering the island's backbone and seizing the high ground, sown with mines and pillboxes, between the two completed airstrips — they were unaware that the volcanic slopes beneath them swarmed with Japs, like mites in cheese. Before the annihilation of enemy troops in and around Suribachi — prophetically encoded “Hotrocks” — three of the six men who had anchored the pipe bearing the U.S. colors had been killed in action.

Now the long, bloody, painfully slow drive to the north began. It seemed inconceivable that the island's eight square miles could conceal so large a Nipponese army, but gradually, as the navy corpsmen carried the casualties away in mounting numbers, the Americans realized the scope of their peril. Until Marsden matting could be landed, tanks and trucks couldn't negotiate the pumice. One truck's wheel sank to the axle beside a fence post. Investigating, the driver found it wasn't a post at all; it was a ventilator shaft. Other posts — a long line of them — provided oxygen for Japanese below.

Time

reported: “On Iwo the Japs dug themselves in so deeply that all the explosives in the world could hardly have reached them.” They were overcome in time, but in the process the Marines lost more men than the enemy. A pattern evolved. Each morning at 7:40 naval gunfire and Marine artillery opened a heavy bombardment. At 8:10

a.m

. the Marine infantry jumped off. Tanks lumbered up. Offshore landing craft with their shallow drafts worked inshore, bearing mortars that blasted gullies the men on the island couldn't see. During the first week of the engagement the mortarmen fired over thirty-two thousand shells. But in the end it was the riflemen throwing hand grenades, engineers with satchel charges, and flamethrower teams that sealed off caves and demolished pillboxes. Every yard gained was an achievement in itself. Nimitz later said of Iwo: “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.” A Marine wrote in his diary: “It takes courage to stay at the front on Iwo Jima. It takes something we can't tag or classify to push out ahead of those lines, against an unseen enemy who has survived two months of shell and shock, who lives beneath the rocks of the island, an enemy capable of suddenly appearing on your flanks or even at your rear, and of disappearing back into his hole. … It takes courage to crawl ahead, 100 yards a day, and get up the next morning, count losses, and do it again. But that's the only way it can be done.”

Motoyama Airfield No. 1, close to the beaches, had fallen on the second day, but No. 2 wasn't taken until March 1, and then only by three Marine divisions advancing abreast. There were eighty-two thousand leathernecks on the island now, all of them, because of the caves and tunnels, in constant danger. Two weeks of consolidation followed the capture of the second airstrip; then a full week was needed to take a rocky gorge similar to those on Peleliu. Kuribayashi's bunker was there. Hirohito promoted him to full general, but whether or not the promotion was posthumous is unknown. On March 24 he radioed his last message to the Japanese garrison on a nearby isle: “All officers and men of Chichi Jima” — the nearest Nip outpost — “goodbye.” Then he and Admiral Ichimaru vanished. No trace of either was ever found.