Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (32 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Whatever the popular image of total Allied air superiority over Western Europe in the last days of the war, in reality it was unnecessary to maintain total surveillance of thousands of cubic miles of sky; the remnants of the Luftwaffe were encircled in an ever-decreasing area. For Allied fighter pilots it was a “target-poor environment”; the very fact that air-to-air encounters were at this point so rare argues that single machines flown by intrepid, experienced, and lucky German airmen could slip across it unnoticed. Since it is established that Leon Degrelle was flown all the way from Norway—and according to Mackensen, via Tønder in southern Denmark—to northern Spain as late as May 8, there is certainly nothing inherently impossible about Hitler having beaten him to it on April 29.

IN BERLIN, BORMAN AND MÜLLER

were meanwhile “tidying up” with ruthless efficiency. During April 28–29, the two actors in the private quarters of the Führerbunker played out a ghastly pantomime orchestrated by the Nazi Party’s grand puppet-master, Martin Bormann. It ended on April 30 in a fatal finale that would have been executed by “Gestapo” Müller. At some time that afternoon Eva Braun’s double was poisoned, and Hitler’s double, probably Gustav Weber, was shot at close range by Müller in person. Shrouded in blankets, the two bodies were carried upstairs to be burned in the shell-torn Chancellery garden, as described by Erich Kempka, the head of the Chancellery motor pool. Although

accounts

by witnesses are confused and sometimes contradictory, this iconic scene has become an accepted historical fact. Indeed, everything about it may be correct—apart from the true identities of the two burning corpses. A picture of an unburnt Hitler “corpse” with a gunshot wound to the forehead circulated extensively after the war. It is now believed to be possibly that of a cook in the bunker who bore a vague resemblance to Adolf Hitler. It was just one of at least six “Hitler” bodies, none of them showing any signs of having been burnt, that were delivered to the Soviets in the days after the fall of Berlin. A third impersonator would also die: Dr. Werner Haase, one of Hitler’s physicians, used a cyanide capsule on Blondi’s double. Her recently born pups—which the Goebbels children loved to play with in the bunker—as well as Eva’s Scottish terriers Negus and Stasi, and Haase’s own dachshund, were killed by Sgt. Fritz Tornow, who served as Hitler’s personal veterinarian.

Bormann communicated the news of “Hitler’s” death to Adm. Karl Dönitz, appointed as the new Reich president in Hitler’s will. Before Bormann and Müller could finish their “cleaning,” there was one more potential witness to be silenced. SS Lt. Col.

Peter Högl

, the last person to have seen Hermann Fegelein, was also shot in the head, as the final groups of would-be escapers left the bunker on the night of May 1–2 (see

Chapter 14

) At this point, SS and Police

Gen. Heinrich Müller

, Bormann’s principal co-conspirator and hit man, disappeared from the “official” history record without a trace. A few days later his family would bury a body in a Berlin cemetery; the casket bore the touching inscription “To Our Daddy,” but it would later be determined that it contained body parts from three unknown victims.

In the early hours of May 2,

Bormann made his own escape

from the Führerbunker along with Werner Naumann, Goebbels’s nominated successor as propaganda minister, who later in 1945 would turn up in Argentina; Artur Axmann, the leader of the Hitler Youth; Hitler’s doctor, Ludwig Stumpfegger; and Waffen-SS Capt.

Joachim Tiburtius

. This party clambered aboard two Tiger II tanks, which tried to make their way up Friedrichstrasse, but the attempt was short-lived. One of the tanks took a direct hit from a Soviet antitank weapon, and the wreck blocked the other Tiger’s path. Bormann and Tiburtius made it on foot separately to the Hotel Atlas; Bormann had already stashed escape clothes, new identity papers, and cash there (as he had at various other points around the city.) Tiburtius and the Reichsleiter pushed on together toward the Schiffbauerdamm, a long road running beside the Spree River in Berlin’s Mitte district; then the SS captain lost sight of Bormann.

The following day Bormann was in the town of Königs Wusterhausen, about twelve miles southeast of the Chancellery. He had been wounded; a shell fragment had injured his foot. He managed to commandeer a vehicle that took him to a German military first aid station for medical treatment. A young, slightly wounded SS sergeant found himself seated alongside a familiar-looking, short, heavyset man wearing a leather overcoat over a uniform stripped of insignia. The young NCO said that he was on his way to the house of his uncle, a Luftwaffe pilot who had been killed in Russia, and invited Bormann to go with him. Joined by another officer, they later walked through the dark streets to the house at Fontanestrasse 9 in the Berlin Dahme-Spreewald neighborhood.

Bormann

later made it safely through the British lines by following the autobahn to the outskirts of Flensburg, where he had planned to make contact with Dönitz. Waiting for him at a safe house just outside the town was “Gestapo” Müller, who had also managed to slip through the British lines. Müller told Bormann that it would be impossible to meet Dönitz, who had by now carried out unconditional surrenders in both Reims and Berlin. The plans had to be changed; Martin Bormann headed south, for the Bavarian mountains.

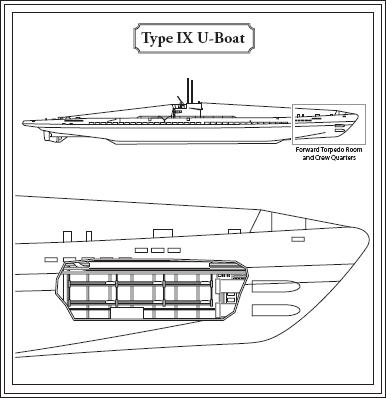

THERE WAS LITTLE OPTION but to choose a submarine as the means to carry Hitler across the Atlantic to Argentina, but it was still a high-risk plan. Since the tipping point in the Battle of the Atlantic in May 1943, the balance of power in the sea war had shifted. The Kriegsmarine had lost its French U-boat bases in the summer of 1944, making the approach voyages to possible patrol areas much longer, more difficult, and more dangerous. Allied antisubmarine naval and air forces with greatly improved equipment now dominated the North Atlantic sea-lanes and the waters around most of Europe, so Allied shipping losses were a small fraction of what they had been. In 1944, U-boat loss rates had outstripped the numbers of new boats being commissioned; consequently, the remaining crews and most of their commanders were much less experienced. From January through April 1945 alone, no fewer than 139 U-boats and their crews were lost. The chances of a successful submarine escape directly from northwest Europe to South America would have been slim; however, the odds improved significantly with Spain as the point of departure.

The only available U-boat class that had the range and capacity to carry passengers to Argentina in anything approaching comfort was the Type IXC. In March 1945, nine Type IX boats sailed for the Atlantic; this was the last major U-boat operation of the war, and the first such operation since the scattering of the failed Gruppe Preussen a year previously. Two of the boats, U-530 and U-548, were directed to operate in Canadian waters, to “annoy and defy the United States.” The other seven, designated

Gruppe Seewolf

—U-518, U-546, U-805, U-858, U-880, U-881 and U-1235—were to form a patrol line code-named Harke (“Rake”). It is believed, however, that in mid-April three of these boats opened sealed orders that would divert them southward on a special mission.

THIS U-BOAT TYPE was designed to be able to operate far from home support facilities. As an example of their endurance, the Type IX boats briefly patrolled off the eastern United States. Some 283 were built from 1937–44.

IT WAS NOT BY CHANCE

that the word “Wolf” was used in the operation’s designation. From early in his career and throughout his life Hitler used the pseudonym Wolf. Among the most successful German operational techniques during the war were the “wolf-pack tactics” (known as

Rudeltaktik

, literally “pack tactics”) by which the U-boats preyed on Atlantic shipping, and the submarines themselves were lauded by the Propaganda Ministry as “Grey Wolves.”

It was typical of Bormann’s meticulous planning that three separate U-boats of Gruppe Seewolf were assigned to the escape mission to provide alternatives if needed and that the mission was concealed within a conventional Atlantic operation so as not to attract Allied curiosity. The planning for this phase of the escape had begun in 1944, when Aktion Feuerland had already been under way for more than a year. On Bormann’s instructions, navy and air force assets across the Reich had been allocated to play contingent parts in the complex and developing escape plan. One such part was a misinformation phase.

IN JULY 1944

,

NEWS AGENCIES REPORTED

that Hitler had approved a plan for an imminent attack on New York, with “

robot bombs

” launched from submarines in the Atlantic. On August 20, the Type IXC boat

U-1229

(Cdr. Armin Zinke) was attacked and forced to surface off Newfoundland on the Canadian east coast, and among the captured survivors was a German agent, Oskar Mantel. Under interrogation by the FBI, he revealed that a wave of U-boats equipped with V-1 flying bombs was being readied to attack the United States. In November 1944, U-1230 landed two agents off the Maine coast; they were spotted coming ashore and arrested. During their interrogation, Erich Gimpel and William Colepaugh (an American defector)

corroborated Mantel’s story

. This also seemed to be supported by the prediction in a radio broadcast by the Reich armaments minister,

Albert Speer

, that V-missiles “would fall on New York by February 1, 1945.”

On December 10, 1944, New York’s mayor Fiorello La Guardia broke the story to an astonished American public. On January 8, 1945, Adm. Jonas H. Ingram, commander of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, announced that a new wave of U-boats approaching the United States might be fitted with V-1 rockets to attack the eastern seaboard. The Nazis might launch “

robots from submarine, airplane or surface ship

” against targets ranging from Maine to Florida, but the U.S. Navy was fully prepared to meet the threat. Many Americans took this

V-1 scare

seriously. The British dismissed it as propaganda, and—with the grim experience of four years’ bombardment and some 60,000 civilian deaths behind them, about 10 percent caused by V-1s—believed that even if such attacks occurred they would not cause a great deal of damage. After all, Hitler’s Operation Polar Bear had succeeded in hitting London with 2,515 V-1s (about one-quarter of those launched), so the handful that might be fired by a few U-boats seemed negligible. On February 16, 1945, a

British Admiralty cable

to the U.S. Navy chief of operations, Adm. Ernest J. King, played down the threat, while conceding that it was possible for U-boats to store and launch V-1 flying bombs. (The Germans had indeed tested a submarine-towed launch platform with some success, but were nowhere near any operational capability. There was even an embryo project, Prüfstand XII, to launch the much larger V-2 ballistic missile at sea from a sealed container, which would be flooded at the base to swing it upright.) However, the planted misinformation achieved its purpose. It would focus American attention toward any detected pack of U-boats, such as the majority of Gruppe Seewolf, thus drawing USN and USAAF assets in the Atlantic eastward and northward—away from the latitudes between Spain’s southern territories and Argentina.

CENTRAL TO THE ESCAPE PLAN

was the use of the

Schnorkel

, a combination of air intake and exhaust pipe for a submarine’s diesel engines, which became widely available from spring 1944. This allowed a U-boat to cruise (very slowly) on diesel power a few feet below the surface, while simultaneously recharging the batteries for the electric motors that had to be used for cruising at any depth. Using the Schnorkel limited a boat’s range to about 100 miles per day; it was normally raised at night, and in daylight hours the boat cruised submerged (again, very slowly) on electric power. While the theoretical ability to remain underwater twenty-four hours a day was a lifesaver for many U-boats, using the Schnorkel was noisy, difficult, and sometimes dangerous, especially in choppy seas. The low speed it imposed robbed the boats of their tactical flexibility on patrol, and remaining submerged made navigation difficult. While no transits to Argentina could have been contemplated without the concealment offered by the Schnorkel, it also worsened the U-boats’ communication problems.