Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (13 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

The country’s roads had been badly neglected during the war. Truman recognized the problem. “In recent years,” he said in 1948, “our highway construction has not kept pace with the growth in traffic…. By any reasonable standard our highways are inadequate for today’s demands.” But construction materials were scarce, and the demand for housing far exceeded the demand for new highways. Not until 1956 would the Federal-Aid Highway Act be signed—by Dwight Eisenhower—creating the interstate highway system and ushering in the golden age of the American road trip.

Now you can drive from San Francisco to New York in less than forty-eight hours.

Considering Harry Truman’s love of roads, it must have bugged him that Eisenhower, not he, came to be known as the father of the interstate highway system.

Around eleven o’clock on the night of Saturday, June 20, the Trumans reached Wheeling, in West Virginia’s northern panhandle between Ohio and Pennsylvania. Just outside of town, Harry noticed a crumbling statue of Henry Clay in a park. “Wheeling, for some reason, used to be devoted to Henry Clay,” he later observed, though he confessed he hadn’t the foggiest idea why. That’s surprising, since the statue (long since removed) was erected to honor Clay for his role in extending the National Road westward from Wheeling.

Harry pulled up in front of the McLure House, a hotel in downtown Wheeling. At the front desk, he very much surprised the night clerk, who recognized him immediately and called the manager. “The manager came up and asked why we had not let him know we were coming,” Truman said. “I told them that if I had, the street in front of the hotel would be so full that we would have a hard time getting through. He agreed that I was right.”

The Trumans checked into a room on the fifth floor and called their daughter, Margaret, who was to meet them in Washington the next day. Margaret had apparently been fielding lots of calls from reporters trying to catch up with her mother and father on the road. America was asking, “Where’s Harry?”

Harry told Margaret that reporters could meet him around four the next afternoon at the Gulf station in Frederick, Maryland. It was where he always filled up before driving into Washington.

When it opened in 1852, the McLure House was the largest and grandest hotel in western Virginia. It had an open courtyard with water troughs and hitching posts for horses. The registration desk was on the second floor, since the open lobby on the first floor was a muddy mess. There was a separate entrance for women, marked L

ADIES

, that was wider than the other entrances, to accommodate the cumbersome hoop skirts that were fashionable at the time.

Over the years, nearly every future, current, or former president who passed through Wheeling spent the night at the McLure House: Grant, Garfield, Arthur, Benjamin Harrison, McKinley, Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, and Wilson. Harry Truman himself had stayed at the McLure before, back when he was a senator.

The McLure was also the site of one of the most notorious political speeches in American history. On February 9, 1950, an obscure senator from Wisconsin, Joseph McCarthy, addressed a meeting of the Ohio County Republican Women’s Club. It was not an event that portended history. McCarthy’s speech, delivered that night in the hotel’s Colonnade Room, contained the usual ad hominem attacks on the Truman administration. Much time was also spent discussing agricultural policy. But it was a single sentence that McCarthy uttered—practically a throwaway line—that immortalized the speech.

“While I cannot take the time to name all of the men in the State Department who have been named as members of the Communist Party and members of a spy ring,” McCarthy said, “I have here in my hand a list of 205 that were known to the Secretary of State as being members of the Communist Party and who, nevertheless, are still working and shaping the policy in the State Department.”

Frank Desmond, the reporter covering the event for the

Wheeling Intelligencer,

included that sentence in his story, though not very prominently: the story jumps from page one to page six in the middle of it. Nonetheless, the Associated Press, cannibalizing Desmond’s story, included the sentence in its own dispatch, which went over the wire that night and appeared in hundreds of papers across the country the next morning.

Challenged to produce the list at a press conference in Denver the next day, McCarthy said he would be happy to—but it happened to be in his other suit, which he’d left on the plane. McCarthy, of course, had no such list. He never did substantiate the charge. But the witch hunt that was engulfing the nation had a champion, and, soon, a name: McCarthyism.

That the McLure was the scene of his hated political enemy’s defining moment concerned Harry Truman not a wit. He wasn’t superstitious. He was just tired. He and Bess had driven three hundred miles from Indianapolis. After chatting on the phone with Margaret, they went to bed.

The McLure House was remodeled, rather disastrously, in the early 1980s. The original red brick exterior was covered with mud-colored concrete panels. A drop ceiling was installed in the lobby, cleverly concealing its vaulted rococo grandeur and rendering it claustrophobic. Harry wouldn’t recognize the place today.

When I stayed at the McLure, I noticed there was a banquet room directly across the hall from my room. It was the Colonnade Room, the very room in which McCarthyism was birthed. The room was locked, but I could see inside through a window in the door. It was dimly lit. White tablecloths covered large round tables, awaiting the next wedding reception. To think of all the misery that ensued from what was said, almost offhandedly, in that room more than a half-century earlier, how many lives were ruined. Was it outweighed by the joy of all the marriages that had been celebrated in there since then? I witnessed an execution once, by lethal injection, at the state penitentiary in Potosi, Missouri. Looking into the Colonnade Room, I had the same feeling I’d had when the cheap Venetian blinds were raised on the window looking into the execution chamber. I was profoundly disquieted. And every time I looked out the peephole in the door of my room, all I could see was the Colonnade Room.

Apart from a large and incongruous group of Russian businessmen in the lobby, I didn’t see any other guests at the McLure the night I stayed there. The place felt a bit sad and ghostly. The water coming out of my bathroom faucet was brown when I first turned it on, a sign that I was the room’s first occupant in a long time.

The next morning I enjoyed a “complimentary continental breakfast” in the Beans 2 Brew Café, the hotel’s coffee shop. This consisted of a prepackaged cinnamon bun and a cup of coffee. Behind the counter was a chatty woman whose every self-amusing sentence ended with a loud, harsh laugh that would mutate into a hacking smoker’s cough. “Would you like me to warm your bun? Ha, ha, ha, hack, hack, cough, cough.” I was afraid she might expel something. I passed on the whole bun-warming thing.

Harry came down to the lobby around eight o’clock the next morning. Dent Williams, a

Wheeling Intelligencer

reporter, cornered him. As he had in Indianapolis, Truman sidestepped questions about Eisenhower and Korea, “because any comment I would make would be a half-baked comment, and Lord knows, I’ve had too many of those half-baked comments.”

But Truman, who had apparently researched local issues in the communities along the route of his trip before leaving Independence, couldn’t resist taking a jab at the Republican-controlled Congress for cutting funding for a floodwall in Wheeling. “Wheeling needs a floodwall badly,” he said, “and I’m sorry to learn that construction funds were stricken from the federal budget.”

He talked about how well the Chrysler was running, how hot it had been in the Midwest, how happy he and Bess were to be on the road again. His only regret, he said, was that he couldn’t travel incognito. “I’ve found that it’s impossible to travel cross-country unnoticed,” he told Williams. As if on cue, Williams overheard a hotel guest tell his young son, “That’s Mr. Truman over there.”

The interview was interrupted when the desk clerk told Harry he had a phone call. The call was transferred to a lobby telephone. After a few minutes, Harry hung up the receiver and returned, smiling, to Williams. “Another nut caught up with me,” the former president said, laughing.

At eight-thirty Bess came down, and the former first couple had breakfast in the hotel’s coffee shop, probably the precursor to the Beans 2 Brew Café.

After breakfast, the Trumans checked out of the McLure. Before paying, though, Harry checked the bill very carefully. If there was one thing he couldn’t stand, it was being overcharged. In 1941—when he was in his second term as a U.S. senator, mind you—he wrote Bess from a Memphis hotel. “Had breakfast in the coffee shop downstairs and they charged me fifty-five centers for tomato juice, a little dab of oatmeal and milk and toast. I don’t mind losing one hundred dollars on a hoss race or a poker game with friends, but I do hate to pay fifty-five centers for a quarter breakfast.”

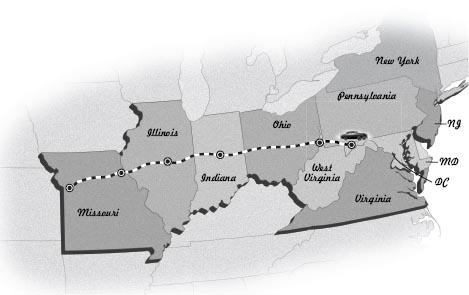

From Wheeling, the Trumans continued east on Highway 40, following the path of the old National Road through the rugged Allegheny Mountains of southwestern Pennsylvania and western Maryland. Near Farmington, Pennsylvania, they passed Fort Necessity, where, during the French and Indian War in 1754, George Washington, then a twenty-two-year-old lieutenant colonel in the British army, suffered one of the worst defeats in his military career, surrendering the fort to French forces. (Incidentally, Washington had been sent to the area to build a road.)

Just past the town of Addison, Pennsylvania, they dipped south into Maryland. Charles Mason and Jeremiah Dixon surveyed the border between Pennsylvania and Maryland in the 1760s. Until then, both colonies claimed the land between the thirty-ninth and fortieth parallels, and in the 1730s they’d even gone to war over it. Mason and Dixon split the difference—their line is about halfway between the two parallels. The Mason-Dixon Line has become the symbolic division between North and South in the United States, though no state that bordered it ever seceded from the Union.

Truman later said he was “impressed with the way the highway over the mountains had been improved from the old blacktop hairpin curves” that he had driven as a senator. If that’s the case, I can’t imagine what traversing the Alleghenies on Highway 40 was like back when Harry was in the Senate, because even today it can be downright scary. The road is twisty, with transmission-killing, ear-popping climbs and hair-raising, brake-burning descents. The car I was driving (my father’s) had just turned a hundred thousand miles back in Ohio, and I felt sorry for having to make it work so hard. It was a far cry from my drive across Illinois, where I could have nodded off at the wheel safely.

I am told there are spectacular views of verdant, tree-covered mountains unfolding under azure skies, but I barely caught a glimpse of any of that, focused as I was on not hurtling off the side of a mountain. It surprised me how precarious the drive was, but U.S. highways are not built to the same standards as interstates, where the maximum grades are generally 6 percent and the minimum design speeds are seventy-five miles per hour in rural areas and fifty-five in mountainous and urban areas.

Near Grantsville, Maryland, I reached the highest point on the old National Road, and the highest point on all of Highway 40 east of the Mississippi: Negro Mountain, elevation 2,827 feet. Local legend has it that the mountain was named after Nemesis, an African American who died fighting for the British in the French and Indian War and was buried on the mountain. The June 10, 1756,

Maryland Gazette

mentions a “free Negro who was … killed” in a “smart skirmish” with local Indians. (On the same page are “ran away” ads, listing the names and detailed physical descriptions of escaped slaves.) But little else is known about Nemesis.

Rosita Youngblood, a state lawmaker from Philadelphia, wants to change the name of the mountain, which extends into Pennsylvania. Youngblood told the

Philadelphia Daily News

her granddaughter discovered the name while working on a seventh-grade class project. “My granddaughter said, ‘Grandmom, is this true?’ I said, ‘There’s no such thing as Negro Mountain.’ Then I learned it was true.” Youngblood has introduced a resolution in the Pennsylvania House calling for the formation of a commission to study the issue. “If they decide to call it Nemesis Mountain,” she said, “I’d be happy with that.”

Youngblood’s crusade baffles lawmakers from rural Somerset County, Pennsylvania, where part of the mountain is located. “I never knew ‘negro’ was a bad word until she mentioned it,” said State Representative Bob Bastian.

Frostburg, Maryland,

June 21, 1953

A

round twelve-thirty the Trumans pulled into Frostburg, a small coalmining town on the eastern slope of Big Savage Mountain in far western Maryland. Looking for a place to eat, Harry had just turned onto a side street when he saw a man in a suit waving him down. Bemused, he stopped the car. The man was Martin Rothstein, the town doctor. Doc—as everybody in Frostburg called him—approached the Chrysler. He recognized the former president immediately.