Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (17 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

That night, Harry “reconvened” his old cabinet for a fancy dinner in a ballroom at the Mayflower. Seated at the head of a horseshoe-shaped table decorated with wildflowers and fruit-filled epergnes, it must have occurred to the former president that he was less well off than any of his subordinates, most of whom had moved on to lucrative careers in the private sector. Dean Acheson, Agriculture Secretary Charles Brannan, Interior Secretary Oscar L. Chapman, and Attorney General James McGranery had all joined high-profile law firms in Washington. Defense Secretary Robert Lovett was a partner at the investment bank Brown Brothers Harriman. Treasury Secretary John W. Snyder was a vice president at the automaker Willys-Overland. Labor Secretary Maurice J. Tobin was a prosperous businessman in Massachusetts.

Dean Acheson gave the toast that night, and it was long remembered by those in attendance as one of the best tributes to Truman—or to anyone, for that matter—they had ever heard. Acheson began by recalling how he’d unexpectedly bumped into his old boss on the street the day before. “At that moment,” he said, “I knew how the Korean prisoners felt when the guards opened the stockade gates.”

Acheson continued,

Mr. President, we are reliably informed that among the Mohammedans the faithful turn to the East when they pray. In Washington the faithful turn to the West. And so your return is to us a very real answer to prayer….

President Truman’s fundamental purpose and burning passion has been to serve his country and his fellow citizens. This devoted love of the United States has been the only rival which Mrs. Truman has had….

The greatest of all commanders never ask more of their troops than they are willing to give themselves…. The president has never asked any of us to do what he would not do. When the time came to fight, he threw everything into it, himself included. And what we all knew was that, however hot the fire was in front, there would never be a shot in the back. Quite the contrary! He stood by us through thick and thin, always eager to attribute successes to us and accept for himself the full responsibility for failure….

It is for reasons such as these that this visit of yours brings us such happiness. These visits of yours must be regular affairs, for we all badly need the refreshment and inspiration that they bring us.

To you, Mr. President, and to your enduring health and happiness, we join in a final toast.

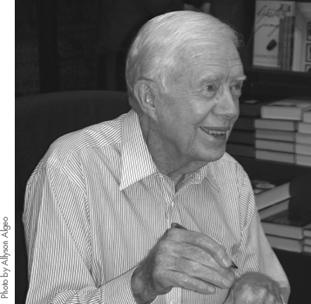

While I was in Washington, another former president returned to the capital—sort of. Jimmy Carter held a book signing at the Books-A-Million in a strip mall in McLean, Virginia, between a wine store and an Advance Auto Parts, and about ten miles west of 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue.

The ex-presidential book signing is a ritual begun by Harry Truman. In a hotel ballroom in Kansas City on November 2, 1955, Harry autographed four thousand copies of his memoirs. According to his publisher, it was the first time an ex-president had “agreed to sit down and sign copies of his book.” Not that Harry was crazy about the idea. “I will go along with any party arrangements you make for Doubleday,” he wrote one of the publisher’s publicists before the event, “but don’t get me into any advertising for pens, cakes or anything, because I won’t do it.”

Jimmy Carter’s book signing was scheduled for 7:00

P.M.

, but when my wife and I showed up at five, about fifty people were already lined up outside the store, which was closed in preparation for the event. A Books-A-Million rep moved up and down the line, making clear the ground rules. Mr. Carter would sign only books—no photographs, no baseballs, no greeting cards. He would sign no more than five books per person, and he would sign only those books that he had authored (he’s written about twenty-five). At least one of the books had to be his new one (A

Remarkable Mother,

his paean to the indefatigable Miss Lillian). He would not personalize inscriptions. He would only sign his name. And he would only sign the title page. We were asked to open our books to that page before presenting them for signing.

Around 5:45, the line started to move. The former president, it seemed, was running early. Three Secret Service agents stationed at the front door gave us the once-over with handheld metal detectors and poked through our bags. The line wound through a maze of bookshelves. Before we knew it, we were in the presence of the thirty-ninth president (or thirty-eighth, by Truman’s reckoning).

He sat behind a large faux mahogany desk with a red velvet rope in front of it. Black drapes covered the bookshelves behind him. Secret Service agents stood sentry at each side of the desk. He was wearing a white dress shirt with blue stripes. He hunched slightly as he signed title pages in rapid-fire succession: J Carter, J Carter, J Carter, J Carter. When I examined his autograph later, I was impressed by its legibility.

When I reached the desk, I handed my books to a Books-A-Million minion, who handed them to the former president. I stepped to the front of the desk as he began to sign them. It reminded me of the “Soup Nazi” episode of

Seinfeld.

A strict protocol was to be observed, but I wasn’t sure what it was. It was so quiet I could hear the sound of the pen scratching across the page as he signed the first book. This was not like bumping into an ex-president outside the Capitol. It felt a little funereal. The very arrangement discouraged interaction. I wasn’t even sure we were allowed to address the former president. But I was determined to ask him … something. We’d purchased only three books for him to sign. Time was running out. Finally, I blurted out, “Mr. President, did you ever meet Harry Truman?” He stopped signing for a moment and looked up at me. His expression was serious. He seemed to be rummaging through his mental filing cabinets. “No,” he said after a moment in his familiar quiet drawl. “I wish I had.” He resumed signing but continued talking. “I never met another Democratic president until Bill Clinton. I did meet Richard Nixon when I was governor. But I was just a peanut farmer before that, so I never met Harry Truman.” With that our books were signed. I said, “Thank you, Mr. President.” He looked up at me and smiled. He had already started signing the next pile of books.

Former president Jimmy Carter signing a book for the author at a Books-A-Million bookstore in McLean, Virginia. In 1955, Harry Truman was the first ex-president to hold a book signing.

Our exchange lasted maybe thirty seconds. Which is probably more face time than anybody else got that night. At his previous book signing, I heard he’d signed sixteen hundred books in ninety minutes. That’s 3.3 seconds per book—less than seventeen seconds for the maximum of five books.

In this regard, at least, Carter defeats Truman. At his signing in Kansas City, Harry averaged about nine books a minute—a relatively leisurely rate of some seven seconds per book. (Unlike Carter, however, Harry signed his full name—and with “mechanical precision,” according to one eyewitness.)

On Wednesday, June 24, Harry went back to the Capitol. In room S-211, a committee room just off the Senate floor, he had lunch with forty-four of the forty-seven Democratic senators then serving, including two first-termers, Lyndon B. Johnson and John F. Kennedy.

Truman regarded both future presidents with some circumspection. He considered Johnson a trifle too ambitious. (Johnson was just twenty-eight when he was elected to the House in 1937. In 1955, at forty-two, he would become the youngest Senate majority leader in history.) Truman also thought Johnson a bit of a suck-up—and not an altogether accomplished one. When Truman’s mother died in 1947, then-Congressman Johnson obsequiously wrote the president, saying he would donate a book in memory of the “First Mother” to the Grandview Public Library. Truman wrote back and thanked Johnson, but added, “I regret to advise you that Grandview has no Public Library.” Johnson biographer Robert A. Caro said the relationship between the two men “would never be particularly warm,” and Margaret Truman said her father “never quite trusted” Johnson.

Toward Kennedy, however, Truman felt something approaching antipathy. Elected to Congress at twenty-nine, Kennedy was no less ambitious than Johnson. But at least Johnson had worked his way up from the hard-scrabble Texas Hill Country. Kennedy embodied the kind of elitist sense of entitlement that Truman despised. Furthermore, Truman never cared for Kennedy’s father, the haughty and overbearing Joe Kennedy, whom Truman had once threatened to throw out a hotel window for belittling FDR. When the younger Kennedy’s religion became an issue in the 1960 presidential campaign, Truman quipped, “It’s not the pope I’m afraid of, it’s the pop.” Truman boycotted the Democratic National Convention in Los Angeles that year, claiming it had been “rigged” in Kennedy’s favor. But when Kennedy won the nomination, Truman, ever the dutiful Democrat, campaigned for him.

There is no record of what occurred inside that committee room during lunch that day. Surely Harry gave his standard pep talk. Jack Kennedy was undoubtedly distracted, maybe even a little nervous, for it was his last day as Washington’s most eligible bachelor. That night, he would announce his engagement to a twenty-three-year-old George Washington University graduate whose “Inquiring Camera Girl” column ran in the

Washington Times-Herald.

Her name was Jacqueline Lee Bouvier.

Lyndon Johnson, meanwhile, was probably gazing covetously at the ceiling of room S-211, on which was painted a magnificent fresco by the Italian artist Constantino Brumidi. When he became majority leader, Johnson made the room his new office.

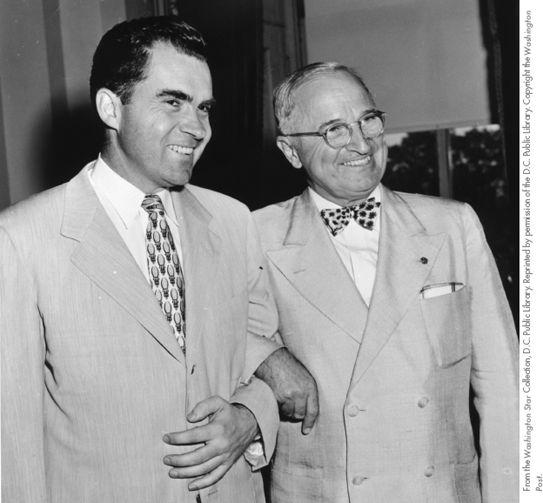

After lunch, the Democratic senators invited Harry onto the Senate floor to visit his old desk. Protocol, however, demanded that he call on the president of the Senate first. So Harry walked across the hall to the office of Richard Nixon and paid what might be the most uncomfortable courtesy call in the annals of Congress. Nixon was one of only two politicians Truman is said to have truly hated. (The other was Lloyd Stark, the Missouri governor who unsuccessfully challenged Truman for his Senate seat in the 1940 Democratic primary.) As a representative and later a senator, Nixon was a constant thorn in Truman’s side. As a member of the House Un-American Activities Committee, he relentlessly pursued charges that communists had “infiltrated” the Truman administration.

But it was the 1952 presidential campaign that forever turned Truman against Nixon. Throughout that campaign, Nixon, the Republican vice presidential candidate, had excoriated the Truman administration for supposedly coddling communists. Nixon said “real Democrats” should have been “outraged by the Truman-Acheson-Stevenson gang’s toleration and defense of communism in high places.” Nixon went “down and around over the country and called me a traitor,” Truman bitterly recalled. He would never forgive Nixon. Privately he called him a “squirrel head,” a “son of a bitch”—or worse.

Harry and Vice President Richard Nixon pose outside Nixon’s office in the Capitol, June 24, 1953. Nixon was one of the two men in politics Harry truly hated.

But in Nixon’s Senate office that warm early summer day, the two consummate politicians did what they knew they had to do. They dutifully posed for photographers, arm in arm, smiling broadly, their mutual contempt nicely concealed. (The papers would say the two men had “buried the hatchet,” a suggestion that made Truman laugh.)

To much applause, Truman was escorted into the Senate chamber by Lyndon Johnson and Senate Majority Leader William Knowland. Truman immediately walked over to Robert Taft, the Ohio Republican who was one of Truman’s fiercest opponents in the Senate. Taft was gravely ill, his body riddled with cancer. Thin and pale, he struggled to his feet with the aid of crutches. The two old foes shared a long, warm handshake. Taft, a perennial presidential candidate, turned to a Republican colleague, Andrew F. Schoeppel of Kansas, and said, “Harry and I have always had the viewpoint that he’d make the best Democratic candidate and I’d make the best Republican candidate for the reason that we each think that the other would be easiest to defeat.” A month later, Taft was dead.