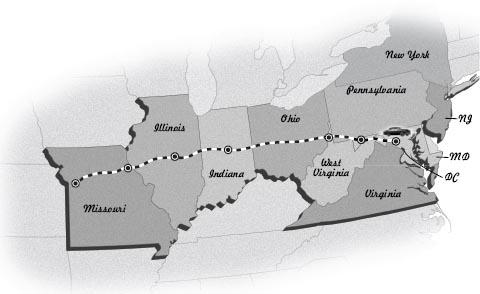

Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip (15 page)

Read Harry Truman's Excellent Adventure: The True Story of a Great American Road Trip Online

Authors: Matthew Algeo

Tags: #Presidents & Heads of State, #Presidents, #Travel, #Essays & Travelogues, #General, #United States, #Automobile Travel, #Biography & Autobiography, #20th Century, #History

One of the reporters asked to use the phone. Carroll Kehne asked him if it was a local call. “No,” the reporter said, “I want to call Margaret Truman to see when her father is supposed to get here.”

“I didn’t believe him at first,” Kehne said. “But the next thing I knew, he”—Truman—“was driving up to the pumps in a beautiful new black Chrysler…. I didn’t know he was coming.”

By now a dozen reporters, photographers, and newsreel cameramen were crowded around the pumps. Kehne filled Truman’s car with gas and checked the oil while his fifteen-year-old son, Carroll Jr., washed the windows. “When President Truman stepped out of the car,” the younger Kehne remembered, “he offered to shake my hand. I stated it was wet, but that didn’t faze him. He said, ‘That’s no problem!'”

“I made up a ticket for his gasoline and made him sign it,” the elder Kehne recalled. “But I wouldn’t let him pay it. I just wanted to be able to say that I treated President Harry S. Truman to a tank of gasoline.”

Harry went inside the station. “The Boss wants a glass of water,” he announced, “and I’d love a Coke.” Leaning on the counter, he spent about twenty minutes chatting with Kehne and Kefauver while he enjoyed his soft drink. “We was talking about everything in general,” Kehne recalled. “He was the kind of guy who could talk to you about anything, fixing cars or changing oil, or politics.” This event, Kehne’s son told me, was the highlight of his father’s life. “My dad was so very excited, as he truly loved Harry as a president. Being a Democrat made it even more pleasant for him.”

At one point, Kehne asked Truman to give Kefauver a hard time for being a Republican. “Na,” said Truman. “It’s too hot to give anybody hell.”

When Truman finished the Coke, Kehne saved the empty bottle.

Back outside, the newspaper photographers and newsreel camera operators asked Harry and Bess to pose with Kehne reading a map. It was preposterous, of course; Harry knew the way to Washington by heart. But he obliged them, smiling, as he always did.

Harry finishes off his Coke at Carroll Kehne’s service station in Frederick, Maryland, June 21, 1953, while Kehne (left) and his mechanic Albert Kefauver watch. When Kehne asked Truman to give Kefauver a hard time for being a Republican, Harry said it was “too hot to give anybody hell.”

Years later, in his memoir

Mr. Citizen,

Truman recalled the scene at the Gulf station:

The press caught up with us at the filling station in Frederick where I had always filled up in times past. I was reminded of the time my mother visited us at the White House. I had wanted her to meet some of these same press correspondents, but I was a little uncertain how she would take to the idea, so I put off saying anything about it until I was leading her from the plane into the midst of them. Then I said: “Mama, these are photographers and reporters. They want to take your picture and talk to you.”

“Fiddlesticks,” she said. “They don’t want to see me. If I had known this would happen, I would have stayed home!”

There on the road in Frederick, I felt the same way she did.

Really? According to the

New York Times,

“Mr. Truman … greeted the photographers and reporters at Frederick like long-lost brothers.” “You’re a sight for sore eyes,” he said.

The newsreel footage of the former president at Carroll Kehne’s Gulf station would be shown in movie theaters around the world. When it was shown at a theater in Whittier, California—Richard Nixon’s hometown—the applause was so loud, according to one attendee, it drowned out the audio.

In 1975 Carroll Kehne closed his service station. He was sixty-five. It was time to retire. Besides, the business was changing. “This is what you call the old, country-type gas station,” he told the

Frederick Post

shortly before the closing. “Where people always gather and have good times. But this is one of the last.”

“All the new stations are concerned with,” he complained, “is just how quick you get in and how quick you get out.”

The Coke bottle that Harry Truman drank from at Carroll Kehne’s service station in Frederick, Maryland, on June 21, 1953. After Kehne died, his son donated the bottle to the Historical Society of Frederick County.

The striking deco service station was torn down shortly after it closed. In its place stands a transmission shop’s nondescript, four-bay garage.

Carroll Kehne died in 1994. Among his belongings, his son found the Coke bottle that Harry Truman had drunk from all those years before. Carroll Jr. donated it to the Historical Society of Frederick County, where it currently resides, lovingly swaddled in acid-free archival paper.

In honor of Harry’s pit stop in Frederick, H. I. Phillips composed a poem for his syndicated newspaper column. It was a spoof on “Barbara Frietchie,” a John Greenleaf Whittier poem about a Frederick woman who became a local hero when she allegedly stood up to Confederate troops during the Civil War.

Up from the meadows rich with corn,

Clear in the steaming mid-June morn,

The gasoline stations of Frederick stand

And give to Harry a hearty hand.

Round about them the tourists sweep;

Clicking and clacking the meters creep;

Routine and drab is the station’s way,

Oftentimes dull … but NOT THIS DAY!

Washington, D.C.,

June 21–26, 1953

A

t 5:40

P.M.

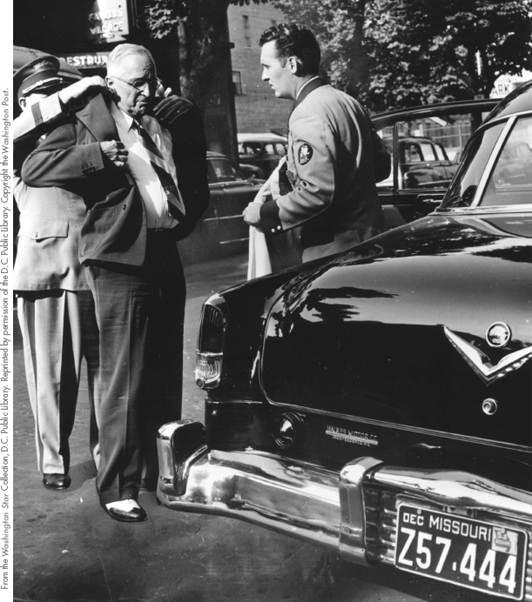

on Sunday, June 21, Harry and Bess pulled up in front of the Mayflower Hotel on Connecticut Avenue in Washington. A doorman helped Harry on with his double-breasted suit jacket. Harry supervised the unloading of luggage.

Never before had a former president returned to the capital quite like this: driving his own car in his shirtsleeves, as if he were nothing more than a curious tourist—which, Harry insisted with a gleam in his eye, is all he was.

Margaret was waiting for her parents at the hotel. She had come down from New York to stay with them while they were in Washington, acting as a kind of unofficial press secretary, a role she clearly relished.

The Truman family stayed in suite 676, which had been redecorated especially for them. (C. J. “Neal” Mack, the hotel manager, jokingly called it the “ex-presidential suite.”) There was a parlor with green walls and white-shaded lamps, a small dining room, two bedrooms, and a kitchen. For this, Mack had agreed to charge the Trumans a “special daily rate” of just fifteen dollars. That was a significant discount: the usual rate was thirty-six dollars.

A doorman helps Harry on with his jacket upon his arrival at the Mayflower Hotel, June 21, 1953. Harry liked the Mayflower so much he called it “Washington’s second-best address.”

Shortly after checking in, Truman invited the reporters who’d covered his return to the capital up to his suite.

“You’re awfully nice to come up here just to see an old has-been,” he said as they filed in. To all questions about politics, Congress, Ike, or Korea, his answer was the same: “No comment.” Mostly he just wanted to talk about the drive from Missouri. It was exactly 1,055 miles from his home in Independence to the Mayflower, he reported. With a touch of pride, he added that his new Chrysler was getting sixteen to seventeen miles a gallon.

The trip, he said, was “wonderful,” “lovely.”

His smile, one reporter noted, was wider than ever.

He said he had no plans to see President Eisenhower. “He’s too busy to see every Tom, Dick, and Harry that comes to town,” he said, putting special emphasis on the last name.

He said he only came back to Washington to see “old friends” and insisted he would be “keeping away from politics.” He was, of course, being disingenuous. Over the next four days Truman presided over a veritable government in exile, meeting with Democratic Party leaders and even calling together his old cabinet. He was back in his element, and he couldn’t have been happier. “He was like a kid on holiday,” journalist Charles Robbins recalled, “exchanging quips with the newsmen, welcoming his former staff and members of his cabinet, hurrying from one telephone to another to talk to senators, representatives, judges.”

And he did it all right under Eisenhower’s nose. The White House, Robbins said, “maintained a tomblike silence” while Harry was in town.

At the time, there was a rumor going around Washington that Truman would run for president again in 1956, with Adlai Stevenson as his running mate—or, perhaps, vice versa. Truman insisted he wasn’t interested in running for anything, but, judging by the way he behaved on his return to the capital, it was hard to believe him.

No hotel has played a more important role in American politics than the Mayflower. Just two weeks after it opened in 1925, it hosted an inaugural ball for Calvin Coolidge (which the famously reticent president did not attend). Herbert Hoover lived at the hotel between his election and inauguration, as did FDR, who wrote his first inaugural address in suite 776. FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover and his longtime aide Clyde Tolson ate lunch side by side in the hotel’s Town & Country Lounge nearly every day for twenty years. Queen Elizabeth and Winston Churchill stayed there. So did the Chinese delegation negotiating détente with the Nixon administration in 1973. Gerald Ford was offered the vice presidency there.

Harry Truman liked the Mayflower. As vice president, he once sat in with the hotel’s band. “He played piano with us (The Fairy Waltz, Chopsticks, etc.) and it was very cozy,” the Mayflower’s bandleader, Sidney Seidenman, wrote in a letter to his son, who was in the army at the time. “He seems a very swell guy. I don’t suppose the German Vice Presidential equivalent would go around playing piano with the likes of me, now, would he?” In a 1948 speech at the hotel, Truman declared his candidacy for election to the presidency in his own right. (“I want to say that during the next four years there will be a Democrat in the White House, and you are looking at him!”) The following January, he celebrated his inauguration there. That was an especially joyous event for Truman, who had, of course, been unable to celebrate his ascension to the presidency theretofore. The Mayflower, he said, was “Washington’s second-best address,” a phrase that now appears on T-shirts sold in the hotel’s gift shop.