Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight (18 page)

Read Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight Online

Authors: Linda Bacon

When is the last time you ate a meal made without opening a can, bag, or jar or handing over money at a drive-through window?

Just consider: In the last 30 years, our annual spending on fast food jumped eighteen-fold—from $6 billion to $110 billion a year.

189

Potatoes used for processed foods like frozen French fries (eaten mostly in fast-food eateries), potato chips, and shoestrings jumped from 8 percent of total U.S. per capita fruit and vegetable supplies in 1970 to 11 percent in 1996. Is it any surprise to find that this jump coincides with the same timeframe in which Americans have gained weight?

189

Potatoes used for processed foods like frozen French fries (eaten mostly in fast-food eateries), potato chips, and shoestrings jumped from 8 percent of total U.S. per capita fruit and vegetable supplies in 1970 to 11 percent in 1996. Is it any surprise to find that this jump coincides with the same timeframe in which Americans have gained weight?

Also not surprising: Research from twenty-one developed countries found that girls who ate fast food at least twice a week were more likely to be heavier than those who ate fast food less frequently.

190

190

Our fast-food culture represents the worst combination of factors I’ve described in this chapter. For those that are genetically vulnerable, consuming it as the major source of your food intake could raise your setpoint. Fast foods—burgers and fried chicken topped off with the high-fructose corn syrup found in everything from buns to special sauce to the coating on those chicken nuggets—lack fiber and many other beneficial nutrients but contain plenty of high-glycemic carbohydrates and saturated and trans fats.

You’ll read more about this culture in chapter 5. For now, a message I want you to take away from this chapter is that the type of food we eat has an effect on the signals that increase or decrease appetite and fat accumulation. The food climate in which we live today clearly plays a role in our collective weight gain.

This fact is not to discount the role of genetics and other factors. To repeat an earlier point, fat people and thin people probably don’t eat much differently from one another. It’s just that some people are more genetically predisposed towards fat storage as a result of particular eating conditions while others burn those calories more efficiently.

Another important message to remember is that just because certain habits may raise one’s setpoint doesn’t mean that reversing those habits will result in weight loss. Differences in the regulatory pathways make weight gain relatively easy though weight loss is resisted. Improved health habits are more likely to result in preventing weight gain than in promoting weight loss.

Now that you know how

what

you eat affects your hunger/fullness/ satiety signals, it’s time to spend a bit of time looking at the effects of

how

you eat on these important signals.

what

you eat affects your hunger/fullness/ satiety signals, it’s time to spend a bit of time looking at the effects of

how

you eat on these important signals.

Ask yourself these questions:

• Do I typically wake up in the morning and rush to work, not stopping to eat regardless of how hungry I am?

• Do I nosh lightly during the day and then have a huge dinner because I am so ravenous?

• Do I super-size whenever I go out, disregarding signals of fullness?

• Do I love the overflowing plates I get in restaurants and eat until I’ve cleaned my plate, regardless of how full I feel?

None are helpful habits to follow if you’re trying to maintain a healthy body. Not surprisingly, the huge portion sizes we get today, and our chaotic eating habits, contribute to difficulty regulating blood sugar and weight.

For instance, several studies find that people who skip breakfast are more likely to be heavy than those who eat first thing in the morning

144

191

and that people who eat four or more meals per day are less likely to be heavier than people who eat three or fewer meals per day.

191

144

191

and that people who eat four or more meals per day are less likely to be heavier than people who eat three or fewer meals per day.

191

This finding is likely related to the “thrifty” gene concept discussed earlier. Missing meals and chaotic eating habits trigger your “starvation defenses,” in which your body does whatever it can to hang onto whatever calorie it can, leading to poor insulin sensitivity and increasing your setpoint. Researchers have also found higher levels of stress hormone levels when people skip breakfast, compared to when they have it.

192

192

We’ve evolved to eat the sorts of foods available to our ancestors, whose genes we’ve inherited and whose bodies we still (more or less) inhabit. Humans have not had much time (at least from an evolutionary perspective) to accustom our bodies to processed foods or the foods from animals raised as they are today. A diet built on a base of whole foods, rich in plants, will better mimic the ancestral diets we were designed for and best support us in maintaining good health—and a healthy weight regulation system.

This is not to suggest that you need to eat whole plant foods

exclusively

! Before you weep over having to abandon your mom’s fried chicken and gravy, remember that there’s no benefit to being extreme. Your body (and your weight regulation system) can effectively be fueled by hamburgers and donuts when they’re consumed in moderation and in the context of an overall nutritious diet. Once you know how to listen to your body’s signals, you’ll get comfortable eating amounts that satisfy you without overdoing it. It’s only in excess that they crowd out more nutritious options, and your body nudges you to get more calories in order to get its varied nutrient needs met. So instead of focusing on taking food away, think about what you want to add for an overall nutritious diet.

exclusively

! Before you weep over having to abandon your mom’s fried chicken and gravy, remember that there’s no benefit to being extreme. Your body (and your weight regulation system) can effectively be fueled by hamburgers and donuts when they’re consumed in moderation and in the context of an overall nutritious diet. Once you know how to listen to your body’s signals, you’ll get comfortable eating amounts that satisfy you without overdoing it. It’s only in excess that they crowd out more nutritious options, and your body nudges you to get more calories in order to get its varied nutrient needs met. So instead of focusing on taking food away, think about what you want to add for an overall nutritious diet.

Here are a few exercises to help you recognize if

what

you’re eating and

how

you’re eating may be compromising your health and triggering your body’s reaction to hold on to excess weight. Identify your challenges here, and future chapters will help you put wholesome habits into practice.

what

you’re eating and

how

you’re eating may be compromising your health and triggering your body’s reaction to hold on to excess weight. Identify your challenges here, and future chapters will help you put wholesome habits into practice.

Is It a Good Food? A Bad Food?There’s one nutritional concept that seems to make a healthy relationship with food particularly difficult, and that’s the idea that some foods are good while others are bad. Labeling a food good or bad stops you from questioning and discovery. If you label a Twinkie as bad, you are not able to observe its effects on you, and you lose the opportunity to learn from it. On the other hand, if you maintain a neutral attitude, you can watch your response to that Twinkie.You can be more perceptive to its flavor, noticing whether it really tastes good to you or if it was just the idea that tasted good. Perhaps you learn that it doesn’t satisfy your craving—that there was something else you really wanted that the Twinkie can’t provide. Perhaps you become more sensitive to your taste buds toning down after the first few bites, making the next bites less pleasurable. Or perhaps you notice that half an hour after indulging in that Twinkie, your energy crashes and you start craving sugar again. This information will ultimately affect your taste for Twinkies in the future.Is eating that Twinkie good or bad? It all depends on how frequently you eat it, how much you eat, what else you eat it with, whether you were attentive to it. . . . Rather than eliminating these variables, we need to listen to them. By staying connected to your body, some foods may lose their appeal or you may no longer feel driven to over-indulge.So, in answer to the question, “Is [fill in the blank] bad?,” the response is, “Of course not.” We simply need to respect it. Let it teach us whether or not we want to indulge or when enough is enough.

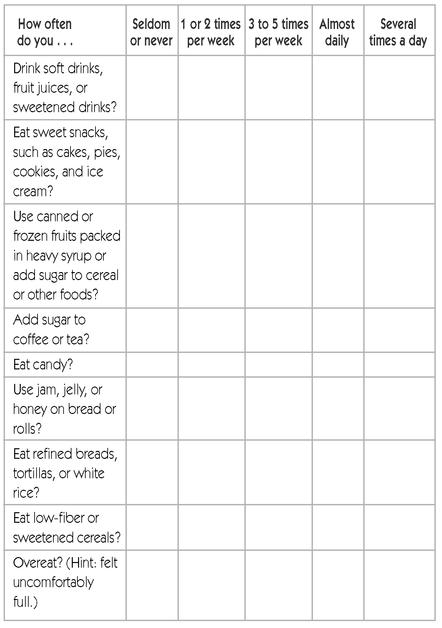

Complete the following charts to learn about your habits.

The Glycemic Rush . . .

If you frequently choose the items listed above, your diet is high in foods that stimulate that quick increase in blood sugar, which may be followed by an over-release of insulin and resultant low blood sugar. While all of these foods can have a place in your diet, a

pattern

of eating these processed, sugary foods—or overeating—may result in increased risk for insulin resistance. You’ll probably notice that it also results in moodiness and energy lows.

pattern

of eating these processed, sugary foods—or overeating—may result in increased risk for insulin resistance. You’ll probably notice that it also results in moodiness and energy lows.

I’m not suggesting you cut out these foods. Just pay more attention to how your food choices make you feel. If you notice that making different types of choices stabilizes your energy and mood, it provides great incentive to make changes. You make these changes because you want to, not because you think you should.

Simple changes—like reducing the amount of these foods you eat, substituting whole grains for refined grains, sweetening cereals with sliced fruit rather than sugar, as opposed to giving up the foods you love—will support your journey. Always keep in mind that foods are not inherently bad: Moderation—which you’ll find happens naturally once you learn to tune into you internal hunger cues—not avoidance, is all you need. Extremism won’t be more effective—and is likely to even work against you.

To figure out how much fiber you consume in a day, write down the number of servings you eat in a typical day for each of the food categories below. Next, multiply by the factor shown—this number represents the average amount of fiber from a serving in that food group. Then add the total amount of fiber consumed.

| Food Group | Number of Servings | Amount (g) |

|---|---|---|

| Vegetables (½ c cooked; 1 c raw) | _______ x 2 g = _______ | |

| Fruits (1 medium; ½ c cut; ¼ c dried) | _______ x 2 g = _______ | |

| Dried beans, lentils, split peas (½ c cooked) | _______ x 6 g = _______ | |

| Nuts, seeds (¼ c; 2 tbsp peanut butter) | _______ x 2 g = _______ | |

| Whole grains (1 slice bread; ½ c rice, pasta; ½ bun, bagel, muffin) | _______ x 2 g = _______ | |

| Refined grains (1 slice bread; ½ c rice, pasta; ½ bun, bagel, muffin) | _______ x 0.5 g = _______ | |

| Fiber in your breakfast cereal (check label) | _______ x ___ g = _______ | |

| Total I | _______ |

39+: According to U.S. government standards, this amount of fiber should keep anyone healthy. If you get more, that’s great too. Some cultures show people routinely getting 75+ grams of daily fiber and enjoying excellent health.

38: If you are male, your fiber meets the U.S.-recommended goal. If you are female, this is great and in excess of what is recommended. But again, getting significantly more than the government recommendations is likely to be even better.

25-37: You consume more fiber than the average American. If you are female, this is good news since your fiber meets the recommended amount (25). However, if you are male, these numbers are below the recommended amount.

15-25: You consume more fiber than the average American (but not enough for optimal health).

10-15: Your intake is similar to the average American intake (but not enough for optimal health).

0-10: Uh oh!

If there is one simple rule of thumb for nutritious eating (supportive of a healthy weight regulation system), it is to follow the fiber. Fiber tends to associate with many other beneficial nutrients— and steers clear of those that are less health-promoting. Fruits, veggies, nuts, beans, and whole grains are always a great idea. High-fiber eating is a great boon for energy and mood stability—and for keeping you satisfied between meals. You’ll also find that it does a great job of supporting comfortable bowel movements. Do you keep magazines in your bathroom? That’s a sure indication that you can benefit from more fiber!

Other books

Darkness Dawns by Dianne Duvall

Extinct by Charles Wilson

Briar's Cowboys by Brynn Paulin

Powerplay by Cher Carson

Savory Deceits by Heart, Skye

Magnificent Folly by Iris Johansen

Forever True (The Story of Us) by Grace, Gwendolyn

A Late Thaw by Blaze, Anna

The Cocoa Conspiracy by Penrose, Andrea

The Dying & The Dead 1: Post Apocalyptic Survival by Lewis, Jack