Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight (19 page)

Read Health At Every Size: The Surprising Truth About Your Weight Online

Authors: Linda Bacon

Think about it: No more straining on the toilet! Incentive enough to make a change, isn’t it?

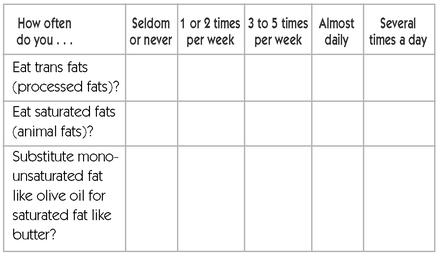

Best to get those trans fats down to minimal, which is getting easier to do these days with increased government regulation. You don’t need them, and even in small amounts they increase your health risk. They’re a marker for low-nutrient foods anyway.

Saturated fats? No need to avoid, just enjoy in moderation. (Saturated fats predominate in animal foods. The easy rule of thumb if your consumption is high is to reduce portion sizes when consuming animal foods, and consider using them as an accompaniment, rather than the centerpiece of your meals.) Also, look for opportunities to substitute monounsaturated fats for saturated fats. Perhaps you can use olive oil rather than butter when sautéing or try “buttering” your (whole grain) bread with ripe avocado.

Switch to a diet lower in saturated and trans fats, and you may also notice more comfort with bowel movements. Check it out!

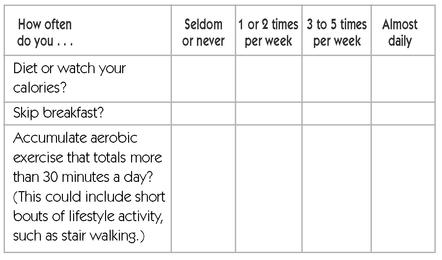

Remember that idea introduced earlier: dieting bad, movement good? Chapter 9 will support you in dumping the diet habit, and chapter 10 will give you some practical (and fun) tips to help you uncover your drive to shake it up.

Take a few moments now to reflect on your reaction to this chapter. Did you find yourself feeling “bad” about your love for soda? Or self-righteous because you only drink water? Did you feel uncomfortable with the message that eating less meat is beneficial? Did you resolve to read food labels and limit your consumption of certain foods in the future?

I want you to consider this information in context. Don’t latch onto anything you’ve learned as new commandments in the what-to-eat /what-not-to-eat game. That simply sabotages your ability to trust your body’s innate system for taking care of you. Future chapters will help you read your body’s messages, supporting you in making shifts because you feel better rather than because you think you should. Your understanding of the science can support you in tuning in.

Don’t jump to the conventional conclusion that you need to carefully watch what you eat—or make dramatic or uncomfortable changes. Sound science supports that when we enjoy a variety of foods and trust our bodies, we naturally get the nutrients we need to keep us healthy. For now, put the focus on getting to know yourself better—and recognizing that there is a very complicated picture behind your drive to eat—or to push yourself away from the table.

And I also don’t want you to give this information more power than it deserves. Truth is, that while environment and how you live your life play a role in directing the action, your genes are in the driver’s seat. Chapter 6 helps you sort this out.

And hang tight, help is on the way. Part 2 helps you establish your game plan for what to do.

FIVE

We’re Victims of Food Politics

P

revious chapters explained that our bodies drive us to eat and to store protective calories to keep us alive and kicking. This chapter shifts focus from our internal mechanisms that keep us eating to the external influences that may determine

what

we eat.

revious chapters explained that our bodies drive us to eat and to store protective calories to keep us alive and kicking. This chapter shifts focus from our internal mechanisms that keep us eating to the external influences that may determine

what

we eat.

The purpose of this chapter is to increase your awareness of how outside influences can affect your current decisions about food. In the second part of the book, you’ll learn how to use your internal cues to guide you in choosing when, what, and how much to eat. Knowledge of what happens behind the scenes can help you figure out what your body truly wants, as opposed to what big companies would have you believe. Use this information to think about what makes sense for

your

body and

your

lifestyle. My intent in drawing attention to these issues is not to scare you away from the foods you love, but to ultimately give you the power to reclaim your tastes and better enjoy your food.

your

body and

your

lifestyle. My intent in drawing attention to these issues is not to scare you away from the foods you love, but to ultimately give you the power to reclaim your tastes and better enjoy your food.

Why is it that the mere aroma of frying food wafting from a McDonald’s can start you salivating, making you crave French fries as if they were gold nuggets? Because the fast-food chain has spent millions in research, marketing, and public relations to ensure this Pavlovian response. Because your choice may be a result of what the companies want you to want—as opposed to what’s right for you. The fast food companies are not the only culprits. Today nearly every processed food manufacturer engages in activities designed to reshape your taste buds, cravings, eating habits, and attitudes toward food, and to co-opt others, like dietitians, researchers, journalists, physicians, and government officials, to deliver their message.

Their tactics have been remarkably successful. Ninety percent of the money Americans now spend on food is spent on processed food.

189

And most Americans prefer the taste of processed foods to whole foods from nature.

Cook’s Magazine

, for example, found in a blind taste test that even chefs preferred vanilla flavoring to actual vanilla.

193

189

And most Americans prefer the taste of processed foods to whole foods from nature.

Cook’s Magazine

, for example, found in a blind taste test that even chefs preferred vanilla flavoring to actual vanilla.

193

Even more disturbing, this corporate manipulation of our palates and food attitudes is being conducted with active government support. In fact, the government, while giving lip service to health promotion, paradoxically encourages the consumption of processed foods (which are of lower nutritional value than whole foods) through farm subsidies and other economic policies.

To understand what’s going on and how our culture—and you—has been manipulated, just follow the money.

Whether they’re developing foods, promoting their products, or projecting an image, food companies are doing it for just one reason: the money. They’re not in it to take care of our health, so don’t trust them when they claim they are. We can hardly blame them; in fact, they’re just obeying the law.

Economic laws dictate that for-profit corporations are obligated to maximize shareholder profits. They are not social service agencies, and they have no responsibility to foster public health or well-being. In fact, a corporate leader who willfully makes a decision to prioritize public health over profit can be sued by shareholders for breach of legal obligation.

This rule of business means that unlike people, corporations usually don’t have a conscience. They’re only obligated to do the right thing if they can justify it as a means towards increased profits.

Here’s how it plays out when it comes to health: If a corporation believes that selling more nutritious food increases profits, they do it. That’s why most food companies reformulated their products to remove trans fats when the federal government required that they list the amount of trans fats on their labels. Not because they wanted to improve their customers’ health—if that were the reason they would have ditched the trans fats years ago—but because now that they had to show how much of this very-bad-for-you fat was in their foods, they faced reduced sales. Plus, by touting that their products were “trans-fat free,” they could provide the perception that the products were healthier, possibly increasing sales to a more health-conscious public.

Call it “nutri-washing,” a handy term coined by public health attorney Michele Simon.

194

It’s what happens when General Mills boasts that its cereals are made with whole grains but doesn’t bother to tell you they’re still full of sugar with an often inconsequential amount of fiber. Or when Skippy touts its low-fat peanut butter but neglects to mention it still has as many calories (and substantially more sugar) than the full-fat version. Or when Slimfast adds some vitamin powder to its products and claims its shakes are a nutritious alternative to real food.

194

It’s what happens when General Mills boasts that its cereals are made with whole grains but doesn’t bother to tell you they’re still full of sugar with an often inconsequential amount of fiber. Or when Skippy touts its low-fat peanut butter but neglects to mention it still has as many calories (and substantially more sugar) than the full-fat version. Or when Slimfast adds some vitamin powder to its products and claims its shakes are a nutritious alternative to real food.

Simon alerts us to a particularly insidious form of nutri-washing: the food companies have even made their own nutrition seal programs to help you choose nutritious foods. You may be comforted to know that Diet Pepsi has been awarded the Smart Spot nutritional seal by PepsiCo. And for that extra turbo-charged nutrient-packed meal, be sure to enjoy it with Pepperoni Flavored Sausage Pizza Lunchables, which was awarded Kraft Foods’ Sensible Solutions seal.

Food companies face unique challenges in their quest to increase profits. Competition is tough and they’ve got to work aggressively to make sure we consume their products—and that we choose their products over those of their competitors’. That justifies the

$36 billion

a year they spend trying to convince us to buy their products, making them the second largest advertisers in the United States.

30

$36 billion

a year they spend trying to convince us to buy their products, making them the second largest advertisers in the United States.

30

Of course, they don’t promote all products equally. For example, you don’t regularly see advertising, promotion—or even brand names—on foods like potatoes or apples. That’s because there’s little profit to be made from selling potatoes (as any farmer will tell you). But put a little (cheap) labor into transforming those potatoes into potato chips, and voilà! Mega profits. Just look at the math: Potatoes in their raw form sell for about 50 cents a pound. Once transformed into potato chips, they sell for about $4 a pound.

The industry calls its work of transforming potatoes into potato chips “added value.” I call it profit, built at the expense of our health. There are lots of great nutrients in that original potato, but few remain in the processed potato chip. Just empty calories (that empty your wallet).

“But I prefer potato chips to baked potatoes,” you protest. “It is added value for me, which is why I lay out the money.” Yes, yes, I know. We’ll talk about your taste preferences later in the chapter. It’s none too surprising if your taste preferences have developed so that you prefer the stuff that generates higher industry profits. Industry has most of us right where it wants us. But for now, let’s keep following the money.

Processed food provides such large profit opportunities because the raw materials they require are almost incomprehensibly cheap. A bushel of corn has more than 130,000 food calories. Enough, in theory, to sustain a person for over two months. A bushel of corn costs only about $4. That means that a full year’s worth of corn calories costs less than $25.

Why so cheap? To put it simply, the government pays to keep it that way.

Unlike most industries, agriculture does not run on the free market basis of demand/supply = price. In the rest of the economic world, the higher the demand and the lower the supply, the higher the price. So if supply is high and demand is low, meaning prices are low, suppliers cut their production to increase price.

In agriculture, however, the opposite occurs because the government pays farmers for certain crops if they can’t sell them at a fair price. This subsidy provides an incentive to farmers to grow more of that crop even if it’s not selling and even if prices are low; they’re still going to get paid for it.

The best example of this policy is what happened to corn production in the early 1970s, when a major agriculture bill provided subsidies to farmers to make up the difference between the cost of producing a product and the market price. For example, if it cost $1 to produce a bushel of corn and the market price is only 75 cents, the government pays the farmer the missing 25 cents, plus a little extra for profit. In 2005, the government distributed more than $22.7 billion in farm subsidies. Subsidy programs are projected to cost more than $190 billion over the next decade.

195

No wonder an estimated 50 percent of grain farmers’ net incomes come from government subsidies.

196

195

No wonder an estimated 50 percent of grain farmers’ net incomes come from government subsidies.

196

Other books

Whiskey Lullaby by Martens, Dawn, Minton, Emily

El Bastón Rúnico by Michael Moorcock

Heaven Is High by Kate Wilhelm

Becoming Maddie (The Casterhouse series Book 1) by Hannah Gittins

Taste of Lacey by Linden Hughes

Wood's Wreck by Steven Becker

The Key West Anthology by C. A. Harms

Legendary by L. H. Nicole

Traitor to the Crown The Patriot Witch by C.C. Finlay

Brittany Loves Bikers: Motorcycle Gang Gangbang by Cherry Allen