Heinrich Himmler : A Life (118 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

During his trip to Germany in June 1942 the Hungarian Prime Minister, Miklós Kállay, had promised Ribbentrop a further 10,000 ethnic Germans for the Waffen-SS.

153

In May 1943 an agreement concerning recruitment was worked out with the Hungarian government.

154

However, Franz Basch, the leader of the ethnic German group, was ‘gloomy’ about its success: the volunteers would lose their Hungarian citizenship; he advocated compulsory enlistment.

155

This is in fact what happened, and in August of 22,000 ‘volunteers’ 18,000 were enlisted as fit.

156

The occupation of Hungary on 12 March 1944 opened up quite new perspectives, from Himmler’s point of view. The Reichsführer-SS planned

to establish a cavalry and two grenadier divisions each from ethnic Germans of Hungarian nationality and ‘Hungarian citizens of mainly German origins’, in other words, a total of six divisions. Evidently in this way he wanted to create another SS army out of thin air.

157

The agreement for such an SS recruitment programme was signed on 14 April 1944.

158

Moreover, Himmler forced the Hungarian government to transfer ethnic Germans serving in the Hungarian army to the Waffen-SS. He had already made the same agreement with the Slovakian government at the beginning of 1944. In this way the SS secured an additional 50,000 ethnic German soldiers from both countries, although too few to create separate divisions for each of them.

159

Of the approximately 25,000 ethnic Germans from Croatia liable for military service around 17,000 were serving in the Waffen-SS after the existing militias, task forces, and Croatian-German territorials had been integrated into the ‘Prince Eugene’ division.

160

A mass mutiny which occurred in the summer of 1943 sheds some light on conditions in the division. As a result, 173 members of the division, all of them ethnic Germans from Croatia, were arrested and sent to Dachau concentration camp. On 17 October Himmler wrote to the divisional commander, Arthur Phleps, in exceptionally moderate terms; evidently he was well aware of conditions in the division, in which many were serving by no means voluntarily. According to Himmler, what was decisive about the case was the fact that the ethnic Germans were being continually insulted by their superiors. In particular, the ‘nice Balkan habit’ had spread of ‘cursing the mother of the person concerned’. Himmler ordered drastic counter-measures. He instructed that ‘in every such case in which NCOs or men curse a comrade’s mother, they are to be shot on the spot’. In particularly serious cases the person should be hanged. He had nevertheless, so he informed Phleps, ‘consigned’ the 173 ethnic Germans to a camp so that they could be trained ‘to be good volunteers of the Waffen-SS’ and improve their knowledge of German.

161

Apart from the recruitment of ethnic Germans and ‘Germanic’ volunteers, from 1942 onwards Himmler began increasingly to recruit men who, in Nazi jargon, were termed ‘ethnic aliens’. As early as 1940 he had formed ‘legions’ in north-west Europe—with limited success, as we have seen—whose members did not have to meet the high ‘racial’ standards of the SS, and during the following years he engaged in massive recruitment in Wallonia and France. But if he was permitting men of ‘Roman’ or other

non-Germanic origins to serve in the SS volunteer divisions then surely this practice could be expanded?

He embarked on one of the most audacious plans in this sphere in February 1943, after he had received Hitler’s approval for establishing a division of Bosnian Muslims along the lines of the Bosnian-Herzogovinan regiments of the Austrian empire.

162

He met with opposition from the Croatian authorities, however. Furious, he told his representative in Croatia, Konstantin Kammerhofer, ‘to intervene using all your weight’.

163

In the end the latter had the recruits conscripted on the basis of the general duty of military service. The men received their training in France and Silesia. Like their predecessors in the Austrian empire, the soldiers of the 13th SS Volunteer Mountain Division (Croatia) wore a red fez (in their combat uniforms it was grey) with a tassel and a badge which combined an eagle, the SS skull, and a swastika. Instead of the SS runes, on their right collar they wore a model of a ‘Handschar’, or scimitar. With reference to that, in May 1944 the division was renamed ‘Handschar’.

Himmler was quite prepared to respect the culture and way of life of his Islamic volunteers, and, as always when he was interested in something, got involved in details. He enquired of the Grand Mufti what Islamic food regulations should be adhered to as far as supplying the division was concerned, and then announced in August 1943 that he would grant to all ‘Islamic members of the SS and police [ . . . ] as an absolute special privilege [ . . . ] that, in accordance with their religious laws, they should never be served pork or sausage containing pork and should never be given alcohol to drink’. He should be informed of all contraventions of this order. And, ‘I also forbid any joking about these matters such as typically occurs among comrades or any “pulling the legs” of the Muslim volunteers’.

164

He also concerned himself with practical questions: the new fezes of the division did not meet with his approval. He told Pohl that their colour had to be changed and they had to be slightly trimmed.

165

Himmler was not only prepared to allow the Grand Mufti to appoint several imams for his Bosnian division, he even aimed to allow members of the division to pursue Islamic studies; indeed, he went so far as to envisage establishing an ‘Islamic institute somewhere in Germany in which the Mufti can train imams so that he can have a corps of priests who are personally loyal to him and at the same time have been appropriately politically trained’.

166

For after all, Islam and Nazism were linked by their common hostility to ‘the Jews’.

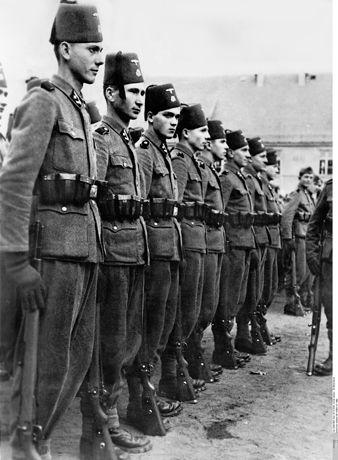

Ill. 31.

The mountain infantry company of the ‘Handschar’ division on the parade ground.

‘Why should anything come between Muslims in Europe and in the whole world and us Germans?’ he asked the 13th SS Mountain Division in a speech in January 1944:

We have the same aims. There can be no more solid a basis for living together than common aims and common ideals. For 200 years Germany has not had the slightest cause for friction with Islam [ . . . ] Now we Germans and you in this division, you Muslims, share a common feeling of gratitude that God—you call him Allah, but it’s the same—has sent our tormented European nations the Führer, the Führer who will rid first Europe and then the whole world of the Jews, these enemies of our Reich, who robbed us of victory in 1918 so that the sacrifice of two million dead was in vain. They are also your enemies, for the Jew has been your enemy from time immemorial.

167

Reading this speech, one might conclude that Himmler’s expression of respect for the world religion of Islam was genuine. In fact, however, his emphasis on common ideals was nothing more than cynical hypocrisy. Two weeks later Himmler reiterated to the Reich propaganda offices why he valued the Croatian volunteers so highly: ‘I must say I have nothing against Islam; for it preaches to its members in this division and promises them paradise if they have fought and died. A practical and agreeable religion for soldiers!’

168

In battle, however, the division disappointed his expectations. Deployed against partisans in their homeland at the end of 1943, the force proved relatively ineffective and, what is more, increasingly rebellious. At the end of 1944 Himmler ended the experiment.

169

Two other Muslim units—the 21st SS Mountain Division ‘Skanderbeg’ composed of Albanians and a Croatian division named ‘Kama’—were also short-lived. Both had been established only in 1944. ‘Skanderbeg’ was dissolved in autumn 1944 and ‘Kama’ appears never to have been ready for combat.

170

As a result, Himmler’s original plan of establishing two army corps of Bosnian and Albanian troops in the Balkans and, by the end of 1944, of combining them with the ‘Prince Eugene Division’ to form an autonomous SS army had failed.

171

In May 1942 Himmler had still been hesitating with regard to Baltic units. At the end of August 1942, however, he approved the establishment of an Estonian legion and shortly afterwards the Wehrmacht transferred a number of Estonian battalions to the Waffen-SS for this purpose.

172

In January 1943 Himmler personally inspected a group of fifty-four Estonian legionaries who were attending a Waffen-SS training course for NCOs, and received

a ‘good impression’ of their ‘racial quality’. He therefore considered it worthwhile to encourage German-language lessons and ideological indoctrination for the soldiers.

173

Himmler never formally recognized the Estonians as Teutons, for that would have brought him into conflict with German occupation policy in that country. In his view, however, they were so similar to Teutons that there would be no danger in racially mixing with them. ‘The Estonians’, so he informed the heads of his Main and Leadership Offices, ‘really belong to the few ethnic groups with whom, after having excluded a very few elements, we could mix without incurring any damage to ourselves.’

174

As we have seen, he had reached similar conclusions about the Slovaks and the Walloons.

At the end of 1942, on Berger’s advice, Himmler secured Hitler’s approval for a Latvian Waffen-SS legion.

175

In April 1943 6,500 Estonians and Latvians had been recruited.

176

The Estonian and Latvian legions were strengthened by the addition of German SS and transformed into the Estonian and Latvian Volunteer Brigades. Shortly afterwards they were expanded into divisions.

177

For this purpose Himmler introduced compulsory military service into the Reich Commissariat Ostland: Estonians and Latvians—Himmler considered Lithuanians unreliable—could now be conscripted into the Waffen-SS.

178

A third Baltic SS division was created out of the police battalions of the auxiliary police, which Himmler had established in 1941.

179

From April 1943 onwards he allowed Ukrainians from the old Austro-Hungarian territory to be recruited for a Galician division. Out of 100,000 applicants 30,000 were accepted.

180

Himmler visited the division, which was given the title 14th SS-Waffengrenadier division after it had completed its training. In a speech to its commanders he dealt, among other things, with criticism that had emerged within its ranks. The tough drill was not harassment, and Galicians too had the possibility of being promoted. To prevent ‘unrest’, he forbade the men to engage in ‘politics’ and, apart from that, preached his list of virtues in a slightly altered form. Apart from obedience, comradeship, and loyalty, he considered it particularly important to explain to the Ukrainians the importance of ‘order’.

181

The division did not last long. It was deployed against the Red Army and in July 1943 almost completely wiped out.

182

The establishment of other ‘ethnic alien’ volunteer units during 1944 met with an equal lack of success. Apart from two Russian, two Hungarian, one

mixed German and Hungarian, and two Cossack divisions, there were several smaller units such as the ‘SS-East Turkish Armed Unit’, the ‘Caucasian Armed Unit’, as well as Serbian, Romanian, and Bulgarian units, and the SS tried to reorganize the Indian legion that had been taken over from the Wehrmacht and had been recruited in POW camps. A British legion, also to be composed from POWs, could not be formed in 1943 because of lack of interest.

If these units were ever deployed—in several cases this did not happen—their military performance was far inferior to that of the average German units.

183

Hitler himself was very critical of the whole programme. In view of the occupation of their homelands the members of these units naturally lacked motivation and were unreliable, as he commented in 1945, shortly before the end of the war. Given the serious shortage of armaments, deploying these units was ‘a luxury’, ‘stupid’, ‘nonsense’.

184

For Himmler, however, their immediate military usefulness was not necessarily the main point. Right from the start of the recruitment programme Himmler had made a sharp distinction between full Waffen-SS divisions, whose members had to satisfy the same ‘racial’ criteria as all other members of the SS, and volunteer units composed of foreigners who did not have to satisfy these criteria. In his view, the big increase in the Waffen-SS must not be allowed to lead to a dilution of the racial criteria for acceptance into the SS.

185

Himmler made it clear, for example, that one should not speak of a Ukrainian SS man, but only of ‘Ukrainians serving in armed units of the SS’. The ‘term SS man, which means so much to us and which we regard so highly,’ should not be used for ‘the numerous members of alien ethnic groups which we are now organizing under the command of the SS’.

186