Heinrich Himmler : A Life (129 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

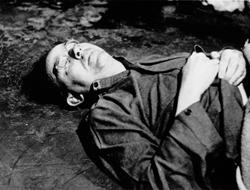

Ill. 32

Himmler’s corpse

Himmler, Grothmann, and Macher continued their march, but on 21 May they landed at a checkpoint near Bremerförde, which had been set up by Soviet POWs released from captivity. On this and the following two days Himmler was sent to several camps, one after the other, until—exhausted but outwardly calm, and without visible emotion—he stood before his British interrogators, who had in the meantime ascertained his identity. The fact that from his perspective only suicide was now an option will have become clear to him during these hours. He could determine only its timing now, and this he wanted to delay. When, however, it became evident that in the course of an alleged medical examination an attempt would be made to remove the poison capsule concealed in his mouth, the moment had arrived: by biting on the capsule he could remain in control to the last.

169

What role did Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler play in the history of National Socialism? How can his contribution to the ‘German catastrophe’ be assessed?

These are the central questions that I have pursued in this biography. If in a number of the preceding chapters I have focused quite intensively on the development of Himmler’s personality, then this was not because I was assuming it would be possible to attribute the Reichsführer’s later misdeeds solely to a defective personality development—for example, to his having suffered childhood trauma or having been socialized in an environment where violence was accepted. Psychoanalytical interpretations have not been the focus of this historical biography. If, however, it is possible to strip away the outer layers to reveal some kind of core personality, then a sensible interconnection between biography and structural history can help us to a better understanding of his political actions. The picture that emerges can be summed up as follows.

Nothing in Himmler’s childhood and youth, spent in a sheltered, conservative Catholic home typical of the educated bourgeoisie of Wilhelmine Germany, would suggest that someone with clearly abnormal characteristics was growing up there. There are no indications at all of any particular problems with his upbringing, of any marked tendency to be cruel, or any noticeable aggressiveness; and it would certainly also be mistaken to see Himmler’s later development as decisively determined by a father–son conflict rooted in an unusually authoritarian upbringing, even granted that the Himmler household was indeed very strict and his father monitored Heinrich down to the detail of how he structured his diary—a tendency to overstep personal boundaries that Himmler was to demonstrate later in life in different circumstances with regard to his SS men. With the exception of

minor skirmishes, however, he does not seem to have reached the point of rebelling against his father; nor is there any evidence of serious political differences between father and son.

If a key to Himmler’s personality is sought in his childhood and adolescence, it is his obvious weaknesses that are striking, and above all the counter-measures he took to overcome them. Physically weak and often unwell, Heinrich was emotionally inhibited and backward in his social development: he suffered from an attachment disorder that made it difficult for him to build up strong and lasting relationships. Throughout his life Himmler was to struggle with these difficulties, which determined his behaviour towards others. Yet he learned to compensate for these deficiencies or to disguise them, on the one hand by means of the strong tendency towards self-control and self-discipline rooted in his upbringing, and on the other by positively drilling himself in the forms and practices of social intercourse.

For Himmler, who was born in 1900, as for many of his generation, the First World War with its far-reaching consequences represented a rupture with the past. Himmler became part of the so-called war youth generation, which, although united by the experience of the war, itself suffered from a complex caused by having been too young to take an active part in it. Though trained as an ensign in 1918, Himmler had no opportunity to serve in the military.

The fact that he had not had the chance to prove himself in combat was responsible in significant measure for his continuing to model himself as a young man on the concept of the ideal soldier, even after he left the army; he regarded himself henceforth primarily as an officer who had been prevented from exercising his vocation. This attitude explains his decision to study agriculture, which was typical of disbanded officers who, seeing themselves as warriors in waiting, were passing the time until the next great conflict by acquiring the skills to earn a living but above all by engaging in a huge range of paramilitary activities.

This soldierly world, which can be summed up in the words: sobriety, distance, severity, objectivity, but also order and regulations, particularly appealed to Himmler with his lack of self-confidence. He was constantly indulging in self-stylizations as a soldierly man, although they remained confined to the realms of the imagination. Though a member of various paramilitary organizations, he took no part in any fighting in the immediate post-war period. The fact that there was little place for women in this male

world made it even more attractive to him, as someone with evident difficulties in relating to women. Himmler was determined, as a soldierly man, not to give in to erotic temptations, and when he was in the grip of them he tried to suppress them with images of violence and war or to act them out through his penchant for voyeurism. He compensated for his lack of experience by interfering in the private lives of others, a tendency that can also be observed when he was Reichsführer-SS. It was only much later that he discerned ‘homosexual dangers’ in this way of life, with its protective cocoon of male solidarity and its self-imposed celibacy, and this was a disturbing insight that strengthened his latent homophobia.

In the years immediately following the First World War Himmler lived in a fantasy world shaped by the paramilitary subculture of the German post-war period; he came into contact with the reality of the Weimar Republic only in 1922, when as a result of the inflation he was unable to embark on a second programme of study and was forced to take up a post as an assistant in a factory that produced fertilizers. In the meantime he had been awarded a diploma in agricultural studies. It was precisely at this point that his politicization and commitment to the radical Right began. Himmler had originally regarded himself as a supporter of the German Nationalist Party, but the general radicalization of politics in Bavaria in 1922–3, and the fact that right-wing conservatives and right-wing radicals merged from time to time, smoothed the way for him to join the Nazis. In doing so he may well have been impressed more by the strong presence of the Nazi movement in the paramilitary world than by the political party as such. His model in this period was above all Ernst Röhm, not Adolf Hitler. It was not until 1923–4 that he gradually developed a coherent völkisch vision, involving also a rejection of the Catholic faith. To the essential elements of this ideology—anti-Semitism, extreme nationalism, racism, and a rejection of modernity—he added occult beliefs and Germanophile enthusiasms; from these elements arose an ideology that was a mixture of political utopia, romantic dream-world, and substitute religion.

The failure of the putsch of 9 November 1923, the subsequent banning of the Nazi Party, and the general economic and political normalization left Himmler, who had now given up his job, on the brink of personal and political bankruptcy. And yet this young man from a comfortably off family decided to remain loyal to the political far Right and harness his professional future to it. His highly developed powers of endurance, coupled with an indulgence in political illusions, his self-image as a soldier, and the fact that

he could see no professional alternative are all likely factors in his decision to commit himself to what at that point was hardly a promising cause. In addition we see a character trait emerging that was to manifest itself repeatedly in Himmler’s political life: failure led him neither to give up nor to turn back, but rather to redouble his efforts in pursuing the goal he had set himself, even if he was to learn to do this in a very flexible manner that corresponded to the power relations at the time. It was precisely these features of his personality that made him persevere with the NSDAP in the coming lean years and made him appear suitable for a ‘soldierly’ role within the party’s paramilitary activities. After a few years as a rural agitator and then as a low-ranking official in the Munich Party Office, and still under the wing of his mentor Gregor Strasser, in 1927 he became deputy Reichsführer of the protection squads, who acted as bodyguards to party members. From the perspective of the party leadership it made sense to place the organization of speaking engagements by prominent party members (for which Himmler, as deputy Reich propaganda chief, was responsible) and their protection in the same hands. Although up to this point he had frequently failed to make a good impression, it was in this position that he finally showed what he could do, and at the beginning of 1929 the leadership of the still fairly insignificant SS fell into his lap.

Himmler now set about building up the SS, which at the point when he took it over comprised only a few hundred members, into the National Socialist movement’s second paramilitary organization. He was helped in this by the long-standing conflict between the party leadership and the SA, which erupted twice, in the summer of 1930 and the spring of 1931, into revolts, above all on the part of the Berlin SA. On both occasions Himmler placed the SS at the party’s disposal as a reliable means of protection. Though the SS remained subordinate to the SA leadership under Röhm, his old mentor, Himmler was nevertheless successful in making the SS stand out as clearly distinct from the SA. His SS was more disciplined, did not provoke the party, and, by contrast with the ruffians in the SA, saw itself as an elite, a feature that manifested itself not least in what purported to be racial criteria for acceptance and permission to marry. Himmler regarded the SS as the racial vanguard for future ‘Blood and Soil’ policies, a claim he strengthened through his alliance with Richard Walther Darré, the party’s agrarian expert and settlement ideologue. In contrast to the ideal of rough, unfettered masculinity propagated by the SA, Himmler advanced the deliberately ‘soldierly’ image of the SS man, who should, if possible, be head

of a clan (

Sippe

) with many children. Himmler’s own new orientation is reflected in this: in 1927 the man who had been a ‘lonely freebooter’ entered into a relationship with Margatete Boden, seven years his senior, and married her in 1928. In 1929 their only child was born.

As this survey of Himmler’s development in his ‘formative years’ reveals, the familiar clichés about his personality do indeed accurately reflect specific characteristics visible in the Reichsführer. His contemporaries frequently thought him impassive, cold, and pedantic. Constantly striving to keep his emotions at a distance and his lack of self-confidence under control, Himmler conducted his relations with others in a manner that was organized down to the smallest detail, and thus made the impression of being insipid and impersonal. He attempted to compensate for the emotional void he felt by taking refuge in utopian dreams and quasi-religious speculations, which in turn were regarded by his contemporaries either as ‘romantic’ or simply as crackpot. Himmler never got too carried away with such daydreams, however; rather, as his first years as Reichsführer-SS showed, he was able to combine ideological flights of fancy with power politics in a an effective manner and to exploit the political power-struggles in the NSDAP for his own purposes, an indication of the extreme utilitarian outlook he had adopted in general. Anything useful to him was permissable. The fact that he did not shy away from violence in the process may not be surprising in the light of his biography. From the outbreak of the First World War Himmler believed himself to be in a military conflict. After experiencing the war for three-and-a-half years from the everyday standpoint of the home front, he had joined the Bavarian army at the beginning of 1918 at the age of 17 and from that time on had moved permanently in circles dominated by the military and by violence. He regarded the turbulent post-war years merely as a continuation of the war and as a chance now to triumph over the enemy within. After the failed putsch he survived by sheltering in the paramilitary environment fostered by right-wing radicalism. As Reichsführer-SS he then regarded himself as a commander in a civil war in which the use of any kind of violence, including political assassination, was permitted.

Himmler assumed the leadership of the SS at a time when Nazism was on the point of rapidly becoming a mass movement, and he was inevitably drawn into the maelstrom of its galloping expansion: in the space of about four years his SS grew to 50,000 members. To make sense of Himmler’s

development from this time it is therefore necessary to trace it with close reference to the history of Nazism as a whole, a history that can be described as the rapid succession of dynamic processes: the conquest, extension, and assertion of power, expansion, racial war of annihilation, and finally progressive self-destruction. Himmler the politician was inextricably bound up in this welter of historical developments; a purely biographical explanation of his political activity would therefore be totally inadequate. We are dealing here with complex political events that cannot be reduced to the psychology of the individual actors.