Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (32 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

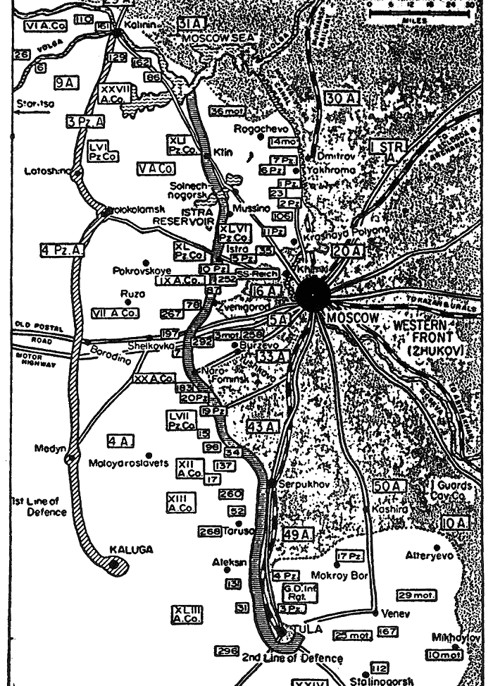

Map 9. On 5th December 1941 the divisions of Army Group Centre were at the gates of Moscow. The city's two lines of defence were breached. Forward units had reached Khimki, 5 miles from the outskirts of the city.

What the men in the open went through during those days, with their machine-guns or anti-tank guns, cowering in their snow-holes, borders on the fantastic. They cried with cold. And they cried with fury and helplessness: they cried because they were within a stone's throw of their objective and yet unable to reach it. During the night of 5th/6th December the most advanced divisions received orders to suspend offensive operations. The 2nd Panzer Division was then 10 miles north-west of Moscow.

At much the same time, during the night of 5th/6th December, Colonel-General Guderian likewise decided to break off the attack on Tula on the southern flank of Army Group Centre, and to take back his far-advanced units to a general defensive line from the Upper Don via Shat to Upa. It was the first time in the war that Guderian had to retreat. It was an ill omen.

To begin with, the new offensive had gone well on his sector. The Second Panzer Army had gone into action with twelve divisions and the reinforced "Grossdeutschland" Infantry Regiment. But the strength of 12 1/2 divisions was only a figure on paper: in terms of fighting strength it amounted to no more than four.

On 18th November Second Lieutenant Stôrck of the 3rd Panzer Division again pulled off a masterly stroke with the Enginers platoon of Headquarters Company, 394th Rifle Regiment. South-east of Tula he seized the railway bridge over the Upa in a surprise coup. This time Stôrck, the bridge specialist, had thought up a very special trick.

The main fighting line ran four miles from the bridge. Four miles of flat, frozen ground with no cover for creeping up to the bridge and taking it by surprise. However, Stôrck realized that the Russians, just as the Germans, clung to the villages at night because of the cold, and he therefore believed that it might be possible in the dark to filter through a thin enemy picket-line.

The plan was put into effect. An assault party of altogether nineteen men with three machine-guns, relying only on their compass, moved softly forward through the black night and the Russian lines. When dawn broke they were 500 yards from the bridge. Then came the second part of the plan.

Störck, Sergeant Strucken, and Lance-corporal Beyle took off their battle equipment and dressed themselves up as German prisoners. Pistols and hand-grenades were stowed away in their overcoat pockets. Two Ukrainians, Vassil and Yakov, who had been with the sapper platoon for the past two months, shouldered their rifles. In their Russian greatcoats and forage caps they looked absolutely genuine. Talking Russian in loud voices, they led their three 'prisoners' towards the bridge while Sergeant Heyeres and his men were waiting under cover.

The first Soviet bridge guard of four men were asleep in two foxholes. The action took only a few seconds, and there was no sound.

Now the five were heading for the 80-yard-long bridge. Their footsteps rang on the hard ground. Vassil and Yakov, talking at the top of their voices, acted their part magnificently. They had nearly got to the bridge when a shadow detached itself from it. A sentry was coming towards them. "Just the man we want," Vassil said loudly. "We are from the next sector, but perhaps you can take these fascists off our hands."

It was all over before the Russian suspected anything. But the second sentry at the end of the bridge was watching intently. And as they came nearer he challenged them, became suspicious, jumped down the bank under cover, and raised the alarm. Too late.

Störck fired two white Very lights. Sergeant Heyeres was already on top of the bridge with his machine-gun and fired for all he was worth. Beyle and Strucken flung their hand-grenades against the dugouts of the bridge guard. The Soviets came staggering out, still dazed with sleep, and raised their hands: 87 prisoners, five machine-guns, two heavy anti-tank guns, three mortars, and an intact assault bridge were the bag made by the handful of German troops. Their cunning and courage had gained the equivalent of a victorious battle.

On 24th November Guderian's 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions and the "Grossdeutschland" Regiment had encircled Tula from the south-east against stubborn resistance by Siberian rifle divisions. The advanced detachments of 17th Panzer Division were approaching the town of Kashira. Just then Lieutenant-Général I. V. Boldin threw his Soviet Fiftieth Army into battle against Guderian's weakened forces. Pressure against the thin and extended German front line became dangerous, since Guderian's adage "We tankmen are in the fortunate position of always having exposed flanks" applied to Blitzkrieg but not to positional warfare.

In a letter to his wife Guderian wrote with bitterness and pessimism:

The icy cold, the wretched accommodation, the insufficient clothing, the heavy losses of men and

matériel,

and the meagre supplies of fuel are making military operations a torture, and I am getting increasingly depressed by the enormous weight of responsibility which, in spite of all fine words, no-one can take off my shoulders.Nevertheless the 167th Infantry Division and the 29th Motorized Infantry Division on 26th November surrounded a Siberian combat group in the Danskoy area, beyond the Upper Don. Some 4000 prisoners were taken, but the bulk of the Siberian 239th Rifle Division succeeded in breaking out.

The encircling forces—in the north the 33rd Rifle Regiment, 4th Panzer Division, in the south and west units of LIII Corps with 112th and 167th Infantry Divisions, in the east units of 29th Motorized Infantry Division—were simply too weak numerically. Magnificently equipped, with padded white camouflage overalls and even their weapons whitewashed, the Siberians again and again attacked the weak encircling forces in night raids, wiped out whoever opposed them, and fought then" way out towards the east between the 2nd Battalion, 71st Motorized Infantry Regiment, and the 1st Battalion, 15th Motorized Infantry Regiment. The German formations were no longer strong enough to prevent a breakout. The battalions of 15th and 71st Infantry Regiments suffered exceedingly heavy losses.

Thus, in spite of all efforts, it proved impossible to capture the surrounded town of Tula —"little Moscow," as it was called—or to drive beyond Kashira, let alone to reach the distant objective of Nizhniy Novgorod, now Gorkiy. True enough, on 27th November the 131st Infantry Division in an easterly push succeeded in talcing Aleksin. Likewise, the 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions succeeded on 2nd December in advancing as far as the Tula-Moscow railway-line and blowing it up. Indeed, on 3rd December the 4th Panzer Division succeeded in reaching the Tula-Serpukhov road at Kostrova. The XLIII Corps thereupon tried once more to link up with the 4th Panzer Division to the north of Tula, and to throw the enemy back to the north. On 3rd December the most forward units of the Corps—the 82nd Infantry Regiment, 31st Infantry Division —got within nine miles of the 4th Panzer Division, but they could not realize their aim. On 6th December the offensive had to be suspended on this sector too. The troops and their vehicles stuck fast in a truly Arctic frost of 30 degrees, and in places 45 degrees, below zero Centigrade.

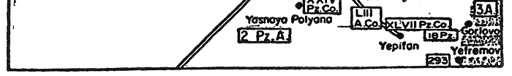

Desperate, Guderian sat over bis maps and reports at his headquarters nine miles south of Tula, in a small manor house famous throughout the world—Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy's estate. In the grounds outside, overgrown with ivy and now deep in snow, was the grave of the great writer. Guderian had allowed the Tolstoy family to keep the rooms in the big house and had moved with his staff into the museum; even there two rooms were set aside for the exhibits and sealed up.

There, in Tolstoy's country house during the night of 5th/ 6th December, Guderian decided to recall the advanced units of his Panzer Army and go over to the defensive. He was forced to admit: "The attack against Moscow has failed. We have suffered a defeat."

- Why couldn't Moscow be taken?

Other books

Derrolyn Anderson - [Marinas Tales #1] - Between The Land And The Sea by Derrolyn Anderson

The Vengeful Vampire by Marissa Farrar

A Year to Remember by Bell, Shelly

Cross Country Christmas by Tiffany King

Ralph Helfer by Modoc: The True Story of the Greatest Elephant That Ever Lived

Glow by Ned Beauman

Terminus by Baker, Adam

Acts of Mercy by Mariah Stewart

The Black God (#2, Damian Eternal Series) by Lizzy Ford

Ridiculous/Hilarious/Terrible/Cool by Elisha Cooper