Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (14 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

At 1700 hours the German tanks received a signal over their radios: "Ammunition must be used sparingly." At the same moment Radio Operator Westphal in his tank heard his commander's excited voice: "Heavy enemy tank! Turret 10 o'clock. Armour-piercing shell. Fire!"

"Direct hit!" Sergeant Sarge called out. But the Russian did not even seem to feel the shell. He simply drove on. He took no notice of it whatever. Two, three, and then four tanks of 9th Company were weaving around the Russian at 800-1000 yards' distance, firing. Nothing happened. Then he stopped. His turret swung round. With a bright flash his gun fired. A fountain of dirt shot up 40 yards in front of Sergeant Horn-bogen's tank of 7th Company. Hornbogen swung out of the line of fire. The Russian continued to advance along a farm track. A German 3-7-cm. anti-tank gun was in position there.

"Fire!"

But the giant just seemed to shrug the shells off. Its broad tracks were full of tufts of grass and crushed haulms of grain. Its engine note rose. The Russian driver was engaging his top gear. That was not such an easy operation with their sturdily built vehicles. Nearly every driver therefore had a hammer lying by his feet; if the gear would not engage, striking the gear-lever with the hammer usually did the trick. A case of Soviet improvisation. Nevertheless, these things moved all right. This one was making straight for the anti-tank gun. The gunners fired furiously. Only twenty yards to go. Then ten, and then five.

Now it was on top of them. The men leaped out of its way, scattering. Like some huge monster the tank went straight over the gun. It then bore slightly to the right and drove on, through the German lines, towards the heavy artillery positions in the rear. Its journey did not end until nine miles behind the main fighting line, when it got stuck in marshy ground a short way in front of the German gun positions. A 10-cm. long-barrel gun of the divisional artillery finished it off.

The tank battle continued into the hours of darkness. Eerily the blazing tanks lay in the cornfield. Tank ammunition exploded, jerricans full of fuel blew up. Medical orderlies darted across the scene, looking for the screaming wounded and covering the dead with blankets or some tent canvas. The crew of the smouldering tank No. 925 laboriously pulled out their heavy skipper—Sergeant Sarge. He was dead. Many were dead who 17 days previously had stood in rank in the forest clearing near Pratulin, listening to the Fuehrer's orders. Many were wounded. But the 17th Panzer Division commanded the battlefield. And he who commands the battlefield is the victor.

There are two reasons why the T-34 did not become a decisive weapon in the summer of 1941. One was the wrong Soviet tank tactics, their practice of using the T-34 in driblets, in conjunction with lighter units or for infantry support, instead of—in line with German thinking—using them in bulk at selected points, tearing surprise gaps into the enemy's front, wrecking his rearward communications, and driving deep into his hinterland. The Russians disregarded this fundamental rule of modern tank warfare, a rule summed up by Guderian in a phrase valid to this day: "Not driblets but mass."

The second mistake of the Russians was in their combat technique. Here the T-34 suffered from one crucial weakness. Its crew of four—driver, gunner, gun-loader, and radio operator-—lacked the fifth man, the commander. In a T-34 the gunner at the same time commanded the tank. This dual function—working the gun and looking out in between— interfered with efficient and rapid fire. By the time the T-34 got a shell out, a German Mark IV had fired three. In this way the German tanks underran the longer range of the T-34s and, in spite of the Russian tanks' massive 4'5-cm. plating, managed to score hits against their tracks and other 'soft spots.' Besides, each Soviet armoured unit had only one radio transmitter— in the company commander's tank. That made them far less mobile in action than their German opponents.

Even so, the T-34 remained a dangerous and much-feared weapon throughout the war. The effect which its mass employment might have had during the first few weeks of the campaign is difficult to imagine. The impression made on the Soviet infantry by the mass employment of German tanks, on the other hand, is described most impressively and

frankly by Guderian's opponent, General Yeremenko. In his memoirs he says:

The Germans attacked with large armoured formations, often with infantrymen riding on the tanks. Our infantry were not prepared for that. At the shout "Enemy tanks!" our companies, battalions, and even entire regiments scuttled to and fro, seeking cover behind anti-tank-gun or artillery positions, causing havoc to the whole combat order, and bunching up near anti-tank-gun positions. They lost their ability to manœuvre, their combat readiness was diminished, and all operational control, contact, and co-operation were rendered impossible.

Yeremenko understood clearly what made the German armour superior to his own. And he drew the necessary conclusions. He issued strict orders that the German tanks must be engaged. His recipe was concentrated artillery-fire, attack by aircraft with bombs and cannon, and, above all, engagement at close range with hand-grenades and with a new close-combat weapon which has to this day kept its German Army nickname —the Molotov cocktail. This weapon, still a great favourite in domestic revolutions, has an interesting history.

By chance Yeremenko learned that in Gomel there was a store of a highly inflammable liquid called KS—a petrol- and-phosphorus mixture with which the Red Army had experimented before the war, probably with a view to setting enemy stores and important installations on fire quickly. Yeremenko, ingenious as ever, immediately ordered 10,000 bottles of the liquid to be delivered to his sector of the front, and issued them to combat units for use against enemy tanks. The Molotov cocktail was no wonder weapon, but a piece of improvisation, a desperate makeshift. But quite often it was highly effective. The liquid burst into flames the moment it came into contact with air. A second bottle, filled with petrol, added to the effect. When only petrol was available an improvised fuse tied to the bottle and lit before throwing did the trick. Provided the bottles burst high up on a tank or on its side-wall, the burning mixture would run into the combat quarters or into the engine, setting the oil and fuel on fire immediately. These large boxes of steel and tin burned surprisingly readily —probably because the metal was usually covered with a film of oil, grease, and petrol.

Needless to say, however, tank armies could not be stopped with petrol bottles, especially once the German tanks— whose strength had always consisted in their close co-operation with the infantry—paid increased attention to enemy troops trying to engage them at close range. If the Russians wanted to halt the Germans, to prevent them from driving via Smolensk to Moscow, they would have to bring up large numbers of men and a lot of artillery.

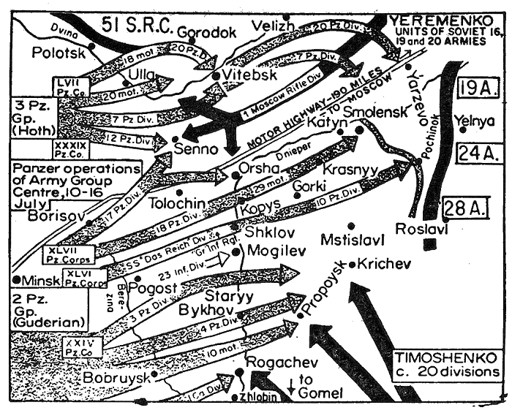

The Soviet High Command therefore switched parts of its Nineteenth Army from Southern Russia to the Vitebsk area. The Russian regiments leaped out of their goods trucks and went straight into battle against Hoth's 7th and 12th Panzer Divisions. Yeremenko realized that he was slowly sacrificing a considerable force of six infantry divisions and a motorized corps. But what else could he do? He hoped that in this way he would at least delay the German spearheads. Time was what he needed.

But Yeremenko's hopes were in vain. The reconnaissance detachment of 7th Panzer Division captured a Soviet officer from an anti-aircraft unit. In his possession were found orders, dated 8th July, which revealed Yeremenko's plan to detrain divisions of the Nineteenth Army north of Vitebsk and employ them on the narrow strip of land between the rivers. Colonel-General Hoth took immediate counter-measures. He ordered Lieutenant-General Stumpff's 20th Panzer Division, which on 7th July had crossed over to the northern bank of the Western Dvina at Ulla, to advance on 9th July along that bank of the river in the direction of Vitebsk. On the neck of land south of the Western Dvina the 7th and 12th Panzer Divisions were meanwhile tying down Yeremenko's forces. Stumpff's tanks, together with the swiftly brought-up 20th Motorized Infantry Division, under Major-General Zorn, drove straight into the Russian rear and caused chaos to the enemy's detraining operations.

It was the early morning of 10th July—the nineteenth day of the campaign. It was to be a day of dramatic decisions. The German Blitzkrieg was still in full swing. Pskov, south of Lake Peipus, had fallen. General Reinhardt's XLI Panzer Corps had pierced the Stalin Line with its 1st Panzer Division and parts of 6th Panzer Division, and on 4th July, after some fierce tank fighting, taken Ostrov. Continuing its swift advance, the northern Panzer corps of Colonel- General Hoep-ner's Fourth Panzer Group, with 36th Motorized Infantry Division and parts of 1st Panzer Division, four days later reached the vital turning-point on the way to Leningrad. Hoep-ner ordered the troops to wheel north-east

towards the city. Perhaps Leningrad would fall even before Smolensk. And if it fell Russia's armed might in the Baltic would collapse. Moscow's northern flank would lie exposed. Then the race could start as to who would first drive into the Kremlin—Hoepner, Hoth, or Guderian? Things were looking hopeful. Maybe Hoepner would repeat his 1939 triumph of Warsaw, when the 1st and 4th Panzer Divisions of his XVI Motorized Corps stood west and south of the Polish capital within eight days of the start of operations.

Two hundred miles south of Pskov was Vitebsk, an important railway junction on the upper Western Dvina, the gateway to Smolensk. And Vitebsk fell. The 20th Panzer Division took it by storm on 10th July. Fanatical Komsomol members had set fire to the town. It was blazing. But Hoth's Panzer divisions needed no quarters for the night. They simply drove past the burning town, forward, farther to the east, into the rear of Smolensk.

On Guderian's sector, too, where the spearheads had crossed the Berezina at Bobruysk and Borisov and were now making for the Dnieper, the most important decision of the 1941 campaign was made on 10th July.

"What's your opinion, Liebenstein?" Guderian asked his Chief of Staff every evening when he returned from the forward lines to his headquarters. "Shall we continue our thrust and force the Dnieper with armour alone, or do we have to wait for the infantry divisions to catch up with us?" It was a question that had been discussed for days at Second Panzer Group's headquarters. And every time the same argument developed. Infantry were better suited than tank regiments for forcing river crossings. On the other hand, a fortnight would pass before the infantry arrived. And what use would the Russians make of a fortnight spent idly by the Germans on the Berezina or in front of the Dnieper? Lieutenant-Colonel Bayerlein, the chief of operations, listed through the Intelligence officer's file on enemy movements. The evidence was there: aerial reconnaissance reported strong motorized units moving towards the Dnieper and the formation of a new Soviet concentration to the north-east of Gomel.

Map 4.

The crossing of the Dnieper on 10th/llth July 1941 and the resulting capture of Smolensk were the first decisive operation of the campaign on the Central Front.The establishment of these new Russian concentrations somewhat damped the optimism of the German High Command as voiced by Colonel-General Halder on 3rd July. Unless the Russians were to be allowed to man the Dnieper line in strength and establish defensive positions speedy action was needed.

In these arguments with his superiors Guderian came out strongly in favour of continuing operations on the central sector, and his staff were unanimously behind him. To-day we know that Guderian's anxieties were justified.

According to Yeremenko's memoirs, as well as the most recent Soviet military publications, Timoshenko, acting in accordance with a decision by the State Defence Committee, had reorganized what used to be the Western Front and personally taken command of the newly formed Army Group Western Sector. In the north and south, the "fronts," the defence zones corresponding to the old Military Districts, were reorganized into Army Groups—the north-western sector under Marshal Voro-shilov, and the south-western sector under Marshal Budennyy.

From 10th July onward Timoshenko collected division after division along the Dnieper. On llth July his Army Group again comprised 31 infantry divisions, seven armoured divisions, and four motorized divisions. To this must be added the remnants of the Fourth Army—those which had escaped from the pocket of Minsk—and parts of the Sixteenth Army, which was being switched from the south to the Central Front. Altogether, 42 combat-ready Soviet divisions were lining up on the upper Dnieper.

Other books

The Taming by Jude Deveraux

A Wicked Deception by Tanner, Margaret

Behind His Eyes - Truth by Aleatha Romig

Wild Instincts: Part 1 (Werewolf Erotic Romance) by Claudia King

The Bride Says Maybe by Maxwell, Cathy

The Killing Code by Craig Hurren

Unicorn Bait by S.A. Hunter

Philip Larkin by James Booth

The Emperor Awakes by Konnaris, Alexis