Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (12 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

In April 1941 a Czech agent named Skvor confirmed a report to the effect that the Germans were concentrating troops on the Soviet frontier and that the Skoda armament works in Bohemia had been instructed to stop fulfilling Soviet orders. Izmail Akhmedov confirms that Stalin wrote in the margin of this report with red ink: "This information is a British provocation. Find out where it comes from and punish the culprit."

Stalin's order was obeyed. Major Akhmedov of the Soviet secret service was sent to Berlin, disguised as a Tass correspondent, in order to find the culprit. There Akhmedov was caught by the war.

Quite clearly the reports of an intended attack by Hitler did not fit into Stalin's concept. His plan was to allow the capitalists and fascists to fight each other to exhaustion, and then he could do as he wished. That was what he was waiting for. That was why he was rearming. And that was also why he wanted to avoid making Hitler suspicious or provoke him into striking prematurely.

For that reason, according to Yeremenko, he prohibited all emergency mobilization or alerting of the frontier troops. In the hinterland, however, Stalin let the General Staff have its own way. And the General Staff, possessing the same secret information about the German offensive plans, set its mobilization in train and deployed its forces in the hinterland, not for an attack but, in the summer of 1941, for defence.

True, Field-Marshal von Manstein, when asked by the author whether in his opinion the Soviet deployment of forces had been offensive or defensive in character, expressed the view he had already stated in his memoirs: "Considering the numerical strength of the forces in the western areas of the Soviet Union, as well as the heavy concentration of tanks, both in the Bialystok area and near Lvov, it would have been quite easy for the Soviets to switch to the offensive. On the other hand, the deployment of Soviet forces on 22nd June did not suggest immediate offensive intentions. . . . One would probably get nearest to the truth by describing the Soviet concentrations as a 'deployment for all eventualities.' On 22nd June 1941 the Soviet forces were unquestionably organized in such depth that they could only be used for defensive operations. But that picture could have been changed very quickly. The Red Army could have regrouped for offensive operations within a very short time."

Colonel-General Hoth, when questioned by the author, repeated the conclusion he had drawn in his excellent study of armoured warfare on the northern wing of the Central Front: "The strategic surprise had come off. But one could not overlook the fact that in the Bialystok bend the Russians had concentrated strikingly large forces, especially mechanized ones, in greater numbers than would seem necessary for defensive operations."

Whichever view one inclines to, Stalin quite certainly did not intend to attack in the summer of 1941. The Red Army was in the middle of a complete change-over in equipment and a reorganization, especially in the armoured groups. New tanks and new aircraft were being supplied to the units. That, most probably, was the reason why Stalin did not want to provoke Hitler into action.

This attitude on the part of Stalin in turn confirmed Hitler in his intentions. Indeed, it might be said that this war and the cruel tragedy which sprang from it were the outcome of a sinister game of political poker played by the two dictators of the twentieth century.

An impartial witness in support of this theory of the political mechanism behind the German-Soviet war is Liddell Hart, the most searching of military historians in the West. In his essay "The Russo-German Campaign," in

The Soviet Army,

he has expounded it convincingly. He believes that it was Stalin's intention to extend his own positions in Central Europe in the course of the German-Allied war, and perhaps, at a suitable moment, extort further concessions from a hard-pressed HitlerLiddell Hart recalls that as early as 1940, while Hitler was still fighting in France, Stalin used the opportunity to

occupy the three Baltic States—although under the German-Soviet secret treaty one of them, Lithuania, belonged to the German sphere of influence. Hitler must have then realized for the first time that Stalin was out to pull a fast one on him while his back was turned.

Shortly afterwards, when the Kremlin issued a 24-hour ultimatum to Rumania, extorting from her the cession of Bessarabia, and in this way drew closer to Rumania's oilfields, which were so vital to Germany, Hitler became nervous. He moved troops into Rumania and guaranteed the country's integrity.

Stalin saw this as an unfriendly act. Propaganda within the Red Army was being tuned more and more to an anti- fascist note. This was reported to Hitler, who promptly strengthened his troops on the Eastern Front. To this the Russians reacted by moving more of their troops to their western frontier.

Molotov was invited to Berlin. But the planned grand-scale understanding between the two dictators about the division of the world—Hitler was prepared to reward the Soviets with parts of the British Empire—did not come off. Hitler, in his egocentric way of looking at things, took this as evidence of Stalin's ill-will. He saw the threat of a war on two fronts and went on record with the words: "I am now convinced that the Russians will not wait until I have defeated Britain." Three weeks later, on 21st December 1940, he signed "Directive No. 21—Event Barbarossa." This contains the significant sentence: "All measures taken by the commanders-in-chief on the strength of this Directive must be unequivocally presented as precautionary measures in the event of Russia changing her attitude to us."

Stalin, on his part, had regarded the German offer to Molotov as a sign of weakness; he felt in a superior position and believed that Hitler, like himself, was merely out for political blackmail. In spite of his information he did not take Hitler's military plans seriously—or at least he did not believe that Hitler would consider he had any reason for striking already. That was why he avoided doing anything that might provide him with such a reason.

How strictly and meticulously—one might almost say, anxiously—Stalin's High Command was made to conform with this attitude is shown by the fact that General Karabichev, then Inspector of Engineers, was strictly forbidden during his tour of inspection in the Brest area at the beginning of June 1941 to visit the most forward frontier fortifications.

Stalin did not wish to create a war atmosphere among the frontier troops; he wanted to avoid anything that looked like war preparations—either to his own troops or to Hitler's intelligence service. Therefore, in spite of the obvious German troop concentrations, the Soviet frontier troops were not on a proper combat-footing; no long-range artillery was in position for use against German reserves beyond the frontier, and no plans existed for heavy-artillery barrages. The consequences of Stalin's disastrous theory were terrible. One striking illustration was the action and destruction of the Soviet 4th Armoured Division.

Major-General Potaturchev, born in 1898—

i.e.,

forty-three years old in the summer of 1941—with his hair and moustache cut à la Stalin, was one of the first Soviet generals in the field to be taken prisoner. Potaturchev was in command of the Soviet 4th Armoured Division at Bialystok, the spearhead of the Soviet defences at a crucial point on the Central Front. The Soviet High Command thought highly of him. He was a member of the Party, the son of a small peasant from the Moscow area. As a lance-corporal under the Tsar he had gone over to the Red Army, and had advanced to the rank of general commanding a division. His story is of considerable interest:"On 22nd June, at 0000 hours [Russian time—

i.e.,

0100 German summer time], I was summoned to Major-General Khotskilevich, GOC VI Corps," Potaturchev wrote in the deposition he made on 30th August 1941 at the headquarters of the German 221st Defence Division. "I was kept waiting because the General had himself been summoned to Major-General Golubyev, the C-in-C Tenth Army. At 0200 hours

[i.e.,

0300 German time] he came back and said to me, 'Germany and Russia are at war.' 'And what are our orders?' I asked. He replied, 'We've got to wait.' "An astonishing situation. War was imminent. The C-in-C of the Soviet Tenth Army knew it two hours before. But he would not, or could not, give any orders other than "Wait!"

They waited two hours—until 0500 German time. At last the first order came down from Tenth Army. "Alert! Occupy positions envisaged." Positions envisaged? What did that mean? Did it mean that the counter-attacks they had rehearsed in many manœuvres should now be launched? Nothing of the sort. The "positions envisaged" for the 4th Armoured Division were in the vast forest east of Bialystok. There the division should go into hiding—and wait.

"When the 10,900-strong division moved off, 500 men were missing. The medical detachment, with an establishment of 150 men, was 125 men short. Thirty per cent, of all tanks were not in working order, and of the rest several had to be left behind for lack of fuel."

That was how a key unit of the Soviet defensive line-up in the Bialystok area moved into action.

But no sooner had Potaturchev got his two tank regiments and his infantry brigade moving than a new order came down from Corps: the tank and infantry units were to be separated. The infantry was ordered to defend the Narev crossing, while the tank regiments were to hold up the German formations advancing from the direction of Grodno.

This order reveals the utter confusion in the Soviet Command. An armoured division was being torn apart and used piecemeal instead of being employed as a whole, frontally or from the flank, in a counter-attack. The fate of Potaturchev and his units was typical of the Soviet collapse in the border area. First they were battered by German Stukas. Admittedly, they did not lose many tanks, but the troops were badly shaken. Nevertheless Potaturchev reached his prescribed line. But then things began to go wrong for him. The advancing German armoured spearheads did not attack him, but thrust past him and cut him off. Potaturchev tried to evade encirclement. His companies got into a muddle, they were caught by German armoured forces, and smashed one by one. The infantry brigade suffered the same fate.

By 29th June Stalin's famous 4th Armoured Division was only a heap of wreckage. The password was "Every man for himself." They sought salvation in the big forest. In twos and threes, at most in handfuls of twenty or thirty men, infantry, artillery, and tank troops made for the woods. The few armoured cars of the 7th and 8th Tank Regiments which had escaped destruction hid out during the day and at night rolled towards the forest of Bialowieza. The vast forest was their only hope.

On 30th June General Potaturchev and a few officers broke away from their men. They intended to make their way on foot to Minsk and fight their way through from there to Smolensk. Potaturchev walked until his feet were sore, and, because he did not want to be seen on the roads as a shambling, bedraggled general, he got some civilian clothes from a farm.

Nevertheless, he was intercepted by the Germans near Minsk and put in a POW cage. There he revealed his identity to the officer of the guard.

- Objective Smolensk

The forest of Bialowieza—The bridges over the Berezina-Soviet counter-attacks—The T-34, the great surprise—Fierce fighting at Rogachev and Vitebsk-Molotov cocktails-Across the Dnieper—Hoth's tanks cut the highway to Moscow—A Thuringian infantry regiment storms Smolensk-Potsdam Grenadiers against Mogilev.

POTATURCHEV'S information surprised his captors: they had had no idea of the division's fire power. The Soviet 4th Armoured Division had 355 tanks and 30 armoured scout-cars; the tanks included 21 T-34s and 10 huge 68-ton KV models with 15.2-cm. guns. The artillery regiment was equipped with 24 guns of 12.2- and 15.2-cm. calibre. A bridge- building battalion had pontoon sections for bridges 60 yards long and capable of carrying 60-ton tanks.

Not a single German Panzer division in the East in the summer of 1941 was so well equipped. Guderian's entire Panzer Group with its five Panzer divisions and three and a half motorized divisions had only 850 tanks. But then, on the other hand, no German Panzer division was so badly led or so senselessly sacrificed as Potaturchev's 4th. It was against the remnants of this division that the German units were engaged in such fierce fighting in the forest of Bialowieza.

"That damned forest of Bialowieza!" the men grumbled. The whole of Germany made the acquaintance of this terrible virgin forest, the last surviving one in Europe. Bavarians and Austrians, men from Hesse, the Rhineland, Thuringia, and Pomerania, fought in this green hell.

The forest of Bialowieza meant ambush. It was a natural strongpoint in the rear and on the flank of the German forces.

There was the village of Staryy Berezov, and, even better remembered, the village of Mokhnata.

Cossack squadrons were galloping across the open country, desperately anxious to gain the cover of the forest. The outposts of 508th Infantry Regiment were trampled down by them. Hooves pounded; sabres flashed. "Urra! Urra!" They got within a hundred yards of the village. Then the 2nd Battery, 292nd Artillery Regiment, smashed the attack with direct fire.

The 78th Infantry Division from Württemberg, the same which later received the title 78th Assault Division, was ordered to break into the green hell of Bialowieza, to comb the forest, and to drive the Russians out towards the intercepting line established by 17th Infantry Division along the northern edge of the huge forest.

The Russians were past masters of forest fighting. The German troops, by way of contrast, had little experience at that time of this difficult form of operation in the uninhabited, swampy forests of Eastern Poland and Western Russia.

Forest fighting had been the poor relation of German Army training, for the German Forestry Commission kept a jealous eye on its woods and plantations. They could only be used with great care. As for virgin forests, the Wehrmacht had none at all for training purposes. The Russians, on the other hand, had practised this type of fighting extensively. Unlike the German infantry, they did not take up position in front of a wood, or on the wood's edge, but invariably right inside it, preferably behind swampy ground. Behind their all-round positions they kept their tactical reserves. In forest fighting, too, the Red Army men preferred the close combat in which they had been trained.

A particular feature of these Soviet defence positions were infantry foxholes which were unidentifiable from the front and provided a field of fire only to the rear; they were intended for picking off the enemy from behind after he had pushed past.

Whereas the German infantry would clear lanes of fire for themselves, if necessary by considerable telling of trees— which, of course, meant they were easily spotted from the air —the Russians worked like Red Indians. They would cut down the undergrowth only up to waist-height, creating tunnels of fire both forward and towards the sides. This gave them cover and a clear field of fire at the same time. The German divisions had to pay a heavy toll before they mastered this kind of fighting. Some of their costliest lessons they learned in the forest of Bialowieza.

On 29th June the 78th Infantry Division moved off in three columns of march—215th Infantry Regiment on the right, 195th Infantry Regiment on the left, and 238th Infantry Regiment in the rear, in echelon. Contact was made with the enemy near the village of Popelevo. Here the last formations of General Potaturchev's scattered 4th Armoured Division, together with parts of three other divisions, brigades, and artillery detachments, had been re-formed into a new regiment, brilliantly led by Colonel Yashin. It was a case of hand-to-hand fighting—man stalking man with hand- grenade, pistol, and bayonet. The artillery was unable to intervene because friend and foe were too closely interlocked. Only the mortars were useful.

The afternoon of 29th June saw a massacre. The 3rd Battalion, 215th Infantry Regiment, succeeded in engaging the Russians in the flank and in the rear. Panic broke out. The Russians fled. Colonel Yashin lay dead by a road-block made of tree-trunks. Popelevo was again silent.

On the following day the division was more careful. The gunners pounded each patch of forest before the companies moved in. "Infantry will enter platoon by platoon!" A white Very light meant: Germans here. Red meant: Enemy attack. Green meant: Artillery fire to be moved forward. Blue meant: Enemy tanks. Yes, tanks—even in the forest the Russians employed individual tanks for infantry support.

By evening 78th Infantry Division was at last through that accursed forest of Bialowieza. The Russians had left behind 600 dead. The regiments had taken 1140 prisoners. Some 3000 Soviet troops were being pushed towards the interception line of 17th Infantry Division. In its two days of fighting in the forest of Bialowieza the 78th Infantry Division lost 114 killed and 125 wounded.

The 197th Infantry Division established its headquarters in the ancient Polish château of Bialowieza. Its regiments were instructed to clear the virgin forest of the last scattered remnants of the enemy, who were still established in

several places and represented a permanent danger behind the line.

The 29th Motorized Infantry Division and the "Grossdeutschland" Infantry Regiment, who were keeping the big pocket around the Russian armies closed in the Slonim area, east of the forest, were involved on 29th lune in fierce fighting against enemy forces attempting to break out. The infantry divisions of the Fourth and Ninth Armies had still not arrived to finish off the encircled Russians. True, they were hastening to the scene, in forced marches along terrible roads, covered in sweat and dust. But until they arrived the pocket had to be kept sealed by the 29th Motorized Infantry Division and Hoth's 18th Motorized Infantry Division, as well as by 19th Panzer Division. These units were itching to be relieved of their prison guard duties; they were anxious to move on, towards the east, towards their great strategic objective— Smolensk.

"We've got to strike at the root of these continuous Russian break-out attempts. We've got to ferret them out of their woods," Lieutenant-Colonel Franz, the Chief of Operations of 29th Motorized Infantry Division, suggested to his commander, Major-General von Boltenstern. The divisional commander agreed.

"Colonel Thomas to the commander!" The CO of the Thu-ringian 71st Infantry Regiment reported at headquarters. Maps were studied. A plan was worked out. And presently Thomas's combat group moved off into the wooded ground on the Zelv-yanka sector, with parts of 10th Panzer Division, Panzerjägers (Panzer killers), two battalions of 71st Infantry Regiment, two artillery detachments, and sappers. They moved in two wedge-shaped formations. The divisional commander went along with them. Only then did they discover the kind of forces they had to deal with— considerable parts of the Soviet Fourth Army which, having rallied at Zelvyanka, were now trying to fight their way out of the pocket to the east. They intended to break through towards the Berezina. There they hoped they would be able to hold a new defensive position, the Yeremenko Line, which they had been told about in radio messages.

Numerically the German formations were greatly inferior. The Russians fought fanatically and were led by resolute officers and commissars who had not been affected by the panic which followed the first defeats. They broke through, cut off Thomas's combat group, moved their tanks against the rear of the 1st Battalion, 15th Infantry Regiment, and tried to recapture the railway-bridge to Zelva.

The divisional staff officers were lying in the infantry foxholes with carbines and machine pistols. Lieutenant-Colonel Franz commanded a hurriedly established road-block of antitank guns. The Russians were stopped. And at long last the German infantry divisions arrived. The 29th Motorized Infantry Division was able to move off to the north, towards new operations of decisive importance. A fortnight later the division's name would be on everybody's lips.

The Berezina, literally the "Birch River," a right-bank tributary of the Dnieper, enjoys a fame of its own in Russian history. It was here that in November 1812 Napoleon, retreating from Moscow, suffered those crushing losses which meant the final end of his Grande Armée. There is no doubt that Yere-menko too had this historic precedent in mind when, in the evening of 29th June 1941, upon assuming command of the Soviet Western Front in the Minsk area, he issued his first order. It ran: "The Berezina crossings are to be held at all costs. The Germans must be halted at the river."

When Yeremenko issued this order he was not yet aware of the full extent of the Soviet disaster on the Central Front. He supposed fighting divisions where none were left. He relied upon defences which had long been abandoned. He wanted to hold the Germans on the Berezina at a time when the marching orders of Guderian's Panzer divisions already mentioned the Dnieper. He placed his hopes in units which were already shuffling into captivity, such as General Potaturchev's 4th Armoured Division.

How Yeremenko's hopes came to naught was recounted to the author by General Nehring, commanding the German 18th Panzer Division. "In the evening of 29th June," Nehring recalled, "the spearheads of 18th Panzer Division had reached Minsk. Parts of Hoth's Panzer Group—the 20th Panzer Division—had taken the city on 28th June. The 18th Panzer Division was ordered to drive past Minsk in the south, along the motor highway, towards Borisov on the Berezina, and to form a bridgehead there. At the time the whole enterprise seemed like suicide, but it was nothing of the sort. However, that could hardly have been foreseen. The division, relying entirely upon itself, thrust some sixty miles into enemy-held territory."

Nehring moved off early on 30th June. Ahead lay excellent new roads. The tank commanders were delighted. But presently the division met Russian resistance from strongly fortified positions. The Russians fought desperately. It was clear that Yeremenko's orders had been : Hold out or die. He needed time to establish a new line of defences. Could the race against time be won? Nehring was determined to outrace Yeremenko. While the bulk of his division was engaged against the Russians he formed an advanced detachment under Major Teege —the 2nd Battalion, 18th Panzer Regiment, and with them, riding on the tanks, men of the regiment's motor-cycle battalion and parts of a reconnaissance detachment, as well as Major Teichert's artillery battalion.

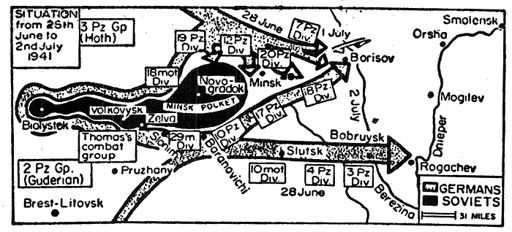

Map 3.

The Bialystok-Minsk pocket. Between Bialystok and Minsk the first great battle of annihilation was fought on the Central Front. Four Soviet Armies were encircled by fast German divisions.By noon on 1st July Teege had reached Borisov. The Russians were taken by surprise but resisted furiously. They were officer-cadets and NCOs of the armoured forces training college in Borisov. They were crack troops. They realized the importance of the bridge over the Berezina. They defended it fanatically, but, strangely enough, did not blow it up. The German advanced detachment suffered heavy losses. Yere-menko threw into the battle whatever he could lay hands on in the Borisov area. But then the bulk of the German division came up. In the early afternoon two battalions of 52nd Rifle Regiment, supported by tanks, launched an assault on the Russian bridgehead on the western bank. 10th Company of this regiment worked its way through the Soviet defences. Sergeant Bukatschek led No. 1 Platoon. He reached the bridge. He fought down the two machine-gun posts on the ramp. He got a rifle bullet in his shoulder, but regardless he raced across the bridge with his men and captured the demolition squad on the other bank before the Soviet lieutenant could push down the plunger.

Teege's tanks and the motor-cycle troops, together with Laube's anti-aircraft battery, crossed the Berezina. The 8-8- cm. guns of the second battery secured the bridge against Soviet attacks. On the following morning, at first light, when Soviet crack battalions drove down the road on lorries from Borisov in order to eliminate the bridgehead, Second Lieutenant Doll with his 8-8-cm. battery blasted the column off the highroad and, at the cost of heavy losses, held the vital bridge against snipers, assault detachments, and tanks. The river, fateful since Napoleon's campaign in Russia, had been conquered. The road to the Dnieper was clear. Fifty miles farther south General Model's 3rd Panzer Division had already crossed the river at Bobruysk, and farther south still 4th Panzer Division, of General Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg's corps, was likewise across and driving towards Mogilev. Yere-menko had lost the round on the Berezina. The date was 2nd July 1941, the day when Alexander Rado in Geneva sent the radio signal to the Kremlin: "The object of the German operation is Moscow."

Other books

Assignment to Hell by Timothy M. Gay

Selling Grace: A Light Romance Novel (Art of Grace Book 1) by Samantha Westlake

Killer Temptation by Willis, Marianne

His Girl Friday by Diana Palmer

Black and Blue (Black and Blue Series) by Khelsey Jackson

Eagle’s Song by Rosanne Bittner

Thrown Down by Menon, David

American Gun Mystery by Ellery Queen

The BlackBurne Legacy (The Bloodlines Legacy Series Book 1) by Apryl Baker

Tying You Down by Cheyenne McCray