Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (43 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

General Châles de Beaulieu believes—and the present author agrees—that Field-Marshal Ritter von Leeb was anxious to let the Commander-in-Chief of Eighteenth Army, who was a personal friend of his, take a prominent share with his infantry divisions in the victory over Leningrad—a psychologically understandable consideration, but one that was to have disastrous consequences. Each day that Stalin gained on the northern sector he used for reinforcing Leningrad's defences with reserves hurriedly scraped together from his vast hinterland, and for reforming in the Oranienbaum area the troops which he had pulled out from the Baltic countries beyond the Luga, thus maintaining his threat to the German northern flank. Every day the German striking formations were held up north-west of Krasnogvardeysk meant that Stalin was getting stronger outside Leningrad. Every day the stubborn defence of Luga continued to tie down German armoured formations reduced the advantage which Hoepner had gained when his fast formations had crossed the Daugava, burst through the Stalin Line, and broken out of their bridgeheads on the Luga. The chances of taking the second biggest city of the Soviet Union, in terms of morale the most important Soviet city, the great metropolis on the Baltic, by a surprise move were steadily fading away.

At last, at the beginning of September, the final attack on the "White City" on the Neva was decided upon—the moment Hoepner's divisions and the forward regiments of the Infantry Corps of Eighteenth Army had so long awaited! Leningrad was the great objective of the campaign in the north. It was an objective every soldier could

understand, an objective which fired every man's fighting spirit.

The signal for the attack was given on 8th and 9th September 1941. The brunt of the attack was to be borne by General Reinhardt's XLI Panzer Corps.

The ground had been very thoroughly reconnoitred, especially from the air. There was no doubt that Zhdanov, Leningrad's Political Defence Commissar and regarded as Stalin's Crown Prince, who shared with Marshal Voroshilov the supreme military command of the Leningrad front, had made good use of the time given him by the continuous postponements of the German attack.

About mid-August the morale of the Soviet troops and the civilian population had been at a dangerously low point following the lightning-like German victories. No one then believed that the city could be defended. Even Zhdanov appears to have toyed with the idea of evacuating it. The delays in the German attack subsequently provided the respite needed by the propaganda machine for stiffening Soviet resistance.

General Zakhvarov was appointed Commandant of the city. For the defence of the city centre he raised five brigades of 10,000 men each. From Leningrad's 300,000 industrial workers some twenty divisions of Red Militia were formed. These factory legionaries continued to be armament workers, but at the same time they were soldiers—workmen in uniform, available for military action at a moment's notice.

In ceaseless day and night toil troops and civilians, including children, were made to build an extensive system of defences around the city. Its main features were two rings of fortifications—the outer and the inner defences.

The outer or first line of defence ran in a semicircle, roughly 25 miles from the city centre, from Peterhof [Now Petrodvorets.] via Krasnogvardeysk to the Neva river. The inner or second line of defence was a semicircle of fortifications in considerable depth, barely 15 miles from the city centre, with the Duder-hof [Now Mozhayskiy.] Hills as their keypoint. The industrial suburb of Kolpino and the ancient Tsarskoye Selo were its cornerstones.

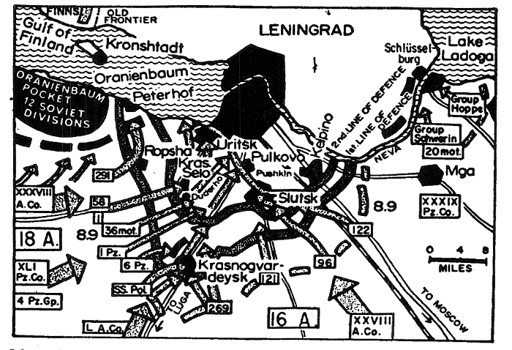

Map 12.

The battle of Leningrad between 8th and 17th September 1941.Aerial reconnaissance had identified a vast number of field fortifications, and behind them enormous anti-tank ditches. Hundreds of pillboxes with permanently emplaced guns supplemented the systems of trenches. This was real assault- troop country, the proper terrain for the infantry. Armour could do no more than drive through the breached defences as a second wave, providing fire cover for the advancing infantry.

The main thrust of Hoepner's Panzer Group against the centre of Leningrad's defences in the area of the Duderhof Hills was to be made by Reinhardt's XLI Panzer Corps. The 36th Motorized Infantry Division formed its spearhead. Behind it 1st Panzer Division was standing ready to follow up the first strike. On the right the regiments of 6th Panzer Division were standing ready for assault. Along the highway from Luga the old Luga divisions—the SS Police Division and the 269th Infantry Division—were to attack towards Krasnogvardeysk under L Army Corps. On the left wing the East Prussian 1st, the 58th, and the 291st Infantry Divisions were employed, as the leading divisions of Eighteenth Army. On the right wing, on the Izhora river, the 121st, the 96th and the 122nd Infantry Divisions were standing ready under the command of XXVIII Army Corps as the striking force of Sixteenth Army. On the extreme eastern wing, along the southern edge of Lake Ladoga, the reinforced 20th Motorized Infantry Division, together with the combat groups Harry Hoppe and Count Schwerin, as part of XXXIX Panzer Corps, had the task of clearing up the bridgeheads of Annenskoye and Lobanov. Their eventual aim was the capture of the town and area of Schlüsselburg.

[Shlisselburg, now Petrokrepost.]

It was on the Duderhof Hills that the Tsars of Russia used to watch the Guards regiments of St Petersburg hold their manœuvres outside the city. The Guards and the Tsars had long passed away, but their experience was alive in the Red Army: every dip in the ground, every patch of woodland, every rivulet, every approach route, and all distances were known with the greatest accuracy. The artillery had the exact range of all the principal points in the terrain. In the infantry dugouts, in the concrete pillboxes, and in the anti-tank ditches all round the Duderhof Hills Zhdanov, Leningrad's Red Tsar, had deployed his Guards—active crack regiments, fanatical young Communists, and the best battalions of Leningrad's Workers' Militia.

Step by step the assault companies of the German 118th Infantry Regiment, 36th Motorized Infantry Division, had to fight their way forward. The entire Corps artillery as well as 73rd Artillery Regiment, 1st Panzer Division, were pounding the Soviet positions, but the Russian pillboxes were magnificently camouflaged and very solidly built.

"We need Stukas," radioed the division's 1st Battalion from where it was pinned down. Lieutenant-General Ottenbacher rang XLI Panzer Corps. The 4th Panzer Group sent an urgent signal to First Air Fleet through its liaison officer. Half an hour later the squadrons of JU-87s of Richthofen's VIII Air Corps came roaring over the sector of 118th Infantry Regiment, banked steeply, plummeted down almost vertically, with an unnerving whine skimmed quite close above the ground, and dropped their bombs on the Soviet pillboxes, machine-gun posts, and infantry gun emplacements. Flashes of fire shot skyward. Smoke and dust followed, forming a dense curtain in front of the still intact enemy strongpoints.

That was the right moment. "Forward!" shouted the platoon commanders. The grenadiers leapt to their feet and charged. Machine-guns clattered. Hand-grenades exploded. The flame-throwers of the sappers sent searing tongues of burning oil through the firing-slits of the pillboxes. Strong-point after strongpoint fell. Trench after trench was rolled up. The men leapt into the trenches. A burst of machine-gun fire along the trench to the right, and another to the left. "Ruki verkh!" ("Hands up!") As a rule, however, the Russians continued to fire until they were hit themselves. In this fashion the 118th Infantry Regiment broke into Leningrad's first line of defence and took Aropakosi. Only when darkness fell did the fighting abate.

On the morning of 10th September the infantry and sappers of the assault battalions had the towering Duderhof Hills in front of them—the bulwark of Leningrad's last belt of defences. This was the key of the second ring round the city. Heavily armed reinforced-concrete pillboxes, casemates with naval guns, mutually supporting machine-gun posts, and a deeply echeloned system of trenches with underground connecting passages covered the approaches of the two all- commanding hills—Hill 143 and, east of it, "Bald Hill," marked on the maps as Hill 167.

Progress was again only yard by yard. Indeed, a dangerous crisis developed for 6th Panzer Division, which was attacking on the right of 36th Division. Alongside 6th Panzer Division, the SS Police Division had been held up in front of a heavily fortified blocking position. But 6th Panzer Division, under Major-General Landgraf, had driven on. The Russians grasped the situation and struck at its flank. Within a few hours the gallant division lost four commanding officers. At close quarters the Westphalians and Rhinelanders struggled desperately to hold the positions they had gained.

From this situation developed the great opportunity of 1st Panzer Division. General Reinhardt turned the 6th Panzer Division towards the east, against the flanking Soviets, and moved 1st Panzer Division into the gap thus created on the right of 36th Motorized Infantry Division.

Lieutenant-General Ottenbacher, with his headquarters staff, was meanwhile close behind the headquarters of 118th Infantry Regiment. His assault battalions were pinned down by heavy fire from the Russians. Ottenbacher once more concentrated his divisional artillery and 73rd Artillery Regiment for a sudden heavy bombardment of the northern ridge of the Duderhof Hills.

At 2045 hours the last shell-bursts died away. The company commanders leapt out of their foxholes. Platoon and section leaders waved their men on. They charged right into the smoking inferno from which rifle and machine-gun fire was still coming. The grenadiers panted, flung themselves down, fired, got to their feet again, and stumbled on. A machine-gunner heeled over and did not rise again. "Franz," his No. 1 called. "Franz!" There was no reply. In a couple of steps he was by his side and flung himself down next to him. "Franz!"

But the second machine-gunner of 4th Company, 118th Infantry Regiment, was beyond the noise of battle. His hands were still clutching the handles of the boxes with the ammunition belts. The box with the spare barrels had slipped over his steel helmet as he fell.

Twenty minutes later No. 1 Platoon of 4th Company leapt into the sector of trench along the northern ridge of the Dud-erhof Hills. The penetration was immediately widened and extended. A keystone of Leningrad's defences had been prised open with Hill 143.

The llth September dawned—a brilliant late-summer day. It was to be a great day for 1st Panzer Division. Colonel Westhoven, commanding 1st Rifle Regiment and an experienced leader of combat groups, led his force against Bald Hill. The main thrust was made by Major Eckinger with his lorried infantry in armoured personnel carriers, the 1st Battalion, 113th Rifle Regiment. It was reinforced by 6th Company, 1st Panzer Regiment, and by one platoon of Panzer Engineers Battalion 37, and supported by 2nd Battalion, 73rd Artillery Regiment.

Major Eckinger enjoyed the reputation of having a good nose. He could smell an opportunity, scent the most favourable spot, and, moreover, had that gift of lightning-like reaction and adaptable leadership that won battles.

Plan and execution of the coup against Hill 167 were a case in point. While 1st Rifle Regiment provided flank cover to the east, the reinforced 113th Rifle Regiment drove along the road to Duderhof and threw back the Russian defenders to the anti-tank ditch of the second line. Eckinger's foremost carrier-borne infantry drove right in among the withdrawing Russians. Sergeant Fritsch with his Panzer sapper platoon burst into the great anti-tank ditch, dislodged the Soviet picket covering the crossing, leapt over it, prevented them from blowing it up, and kept it open for the German units. With the aid of trench ladders they negotiated the steep faces of the ditch to the right and left. They put down beams and planks, and provided crossings for the bulk of the armour and armoured infantry vehicles which followed hard on their heels. The companies of Eckinger's battalion were riding into the line on top of the tanks and armoured troop carriers.

It was a thrilling spectacle. Above the battalion's spearhead, as it raced forward, roared the Stukas of VIII Air Corps. They banked and accurately dropped their bombs 200 to 300 yards in front of the battalion's leading tanks, right on top of the Russian strongpoints, dugouts, ditches, tank-traps, and anti-tank guns.

Luftwaffe liaison officers were in the tanks and armoured infantry carriers of the spearhead and also with the

commander of the armoured infantry carrier battalion. A Luftwaffe signals officer, sitting behind the turret of Second Lieutenant Stove's tank No. 611, maintained radio contact with the Stukas. A large Armed Forces pennant on the tank's stern clearly identified him as the "master bomber." In the thick of enemy fire the Luftwaffe lieutenant directed the Stuka pilots through his throat microphone.

Other books

Angel on Fire (Motorcycle Club Romance) by Lawson, Kelly

Wedding Cake Wishes by Dana Corbit

Blind Ambition by Gwen Hernandez

Game for Marriage by Karen Erickson

Tracking Bear by Thurlo, David

The Pledge by Laura Ward, Christine Manzari

Wet Ride (Toys-4-Us) by Cayto, Samantha

Christmas at Evergreen Inn by Donna Alward

Into the Sea of Stars by William R. Forstchen

Knight (Political Royalty Book 1) by Evelyn Adams