Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (20 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Bayerlein confirmed the anxieties of his Commander. "I was on the phone to Second Army yesterday. Freiherr von Weichs seems to be worried about it too. Lieutenant-Colonel Feyera-bend, their chief of operations, has had reports from long-range reconnaissance about the Russians beginning to withdraw from the Dnieper front below Kiev. At the same time, work has been observed in progress on positions in the Donets area."

"Well, there you are." Guderian was getting heated. "Bu-dennyy has learnt his lesson at Uman. He's slipping through the noose. Everything now depends on which of us is quicker."

But Guderian and Weichs need not have worried. True, Budennyy had realized the danger threatening his Army Group in the Dnieper bend around Kiev from a German thrust jointly from the north and the south. He had planned his withdrawal and was building up new lines of interception along the Donets. But Stalin would not hear of a withdrawal. On the contrary, he squeezed another twenty-eight major formations into the already packed river-bend. Whatever came off the assembly lines of the famous tank factories in Kharkov was thrown into the Dnieper bend—the modern

T-34s, the T-28s, super-heavy self-propelled guns, heavy artillery, and multiple mortars.

"Not a step back. Hold out and, if necessary, die," was Stalin's order. And Budennyy's Corps obeyed. Rundstedt's divisions on the northern wing of his Army Group soon discovered it. The experienced 98th Infantry Division from Franconia and the Sudetenland lost 78 officers and 2300 other ranks within eleven days of fighting for the key point of Korosten. The battle on the Desna between Guderian's and Yeremenko's divisions also went on for eight days. It was a terrible battle—a fierce struggle for every inch of ground. "A bloody boxing match," was Guderian's description. But then came the moment, a lucky accident exploited by a bold operation, when the tide was definitely turned against Budennyy.

In the afternoon of 3rd September the Intelligence officer of XXIV Panzer Corps placed a dirty and charred bundle of papers on the desk of his Corps commander, General Geyr von Schweppenburg. The papers came from the bag of a Soviet courier aircraft that had been shot down. Geyr read the translation, studied the map, and beamed. The papers clearly revealed the weak link between the Soviet Thirteenth and Twenty-first Armies. At once Geyr moved his 3rd Panzer Division against that gap. Guderian was informed by telephone.

The next morning Guderian turned up at Geyr's headquarters. It had taken him four and a half hours by car to cover the 48 miles: such was the condition of the roads after only a short rainfall. But he was cheered by the news awaiting him at Geyr's headquarters. General Model's 3rd Panzer Division had in fact driven into the gap in the Soviet lines. His tanks had torn open the flanks of the two Soviet Armies. As through a burst dam, the rifle regiments and artillery battalions were now spilling through to the south.

Guderian at once drove to Model. "This is our chance, Model." There was no need for him to add anything. Model's units were already racing to the Seym and towards Konotop in a headlong chase. Three days later, on 7th September, the advanced battalion of 3rd Panzer Division under Major Frank succeeded in crossing the Seym and establishing a bridgehead.

On 9th September the 4th Panzer Division likewise crossed the river. Stukas, supporting the experienced 35th Panzer Regiment and the 12th and 33rd Rifle Regiments, blasted the way for them through units of the Soviet Fortieth Army which had been freshly launched against the bridgehead. The Russians began to fall back.

Meanwhile Model's 6th Panzer Regiment was still outside Konotop. At the "Wolfsschanze" in East Prussia and in Bock's headquarters in Smolensk Guderian's headlong rush was being followed intently. It was important that Colonel- General von Kleist, down in the south, should be given his starting order at the right moment.

Major Frank had thrust past Konotop.

Army Group at once rang up Guderian: "Final order: drive towards Romny. Main pressure on the right." That meant that the pocket around Budennyy was to be closed in the Romny area. It was there that Guderian's and Kleist's tanks were to meet.

Romny had been the headquarters of King Charles XII of Sweden in December 1708; 93 miles away was Poltava,

where Tsar Peter the Great inflicted a crushing defeat on the Swedes in 1709. The battle was the death-blow to Sweden's Nordic empire, and marked the emergence of Russia as a modern great power in history. Was this era now to come to an end again at Romny?

Everything went like clockwork. Guderian's tanks achieved the decisive breakthrough at Konotop. It was pouring with rain. But victory lent the troops new strength. The spearheads of 3rd Panzer Division were racing towards Romny.

They were far in the rear of the enemy. But where was Kleist? Where was the second prong of the vast pincers? He had been held back wisely so that the Russians should not realize prematurely the disaster that was about to overtake them.

In the evening of 10th September Kleist's XLVIII Panzer Corps, commanded by General Kempf, reached the western bank of the Dnieper near Kremenchug, where the Soviet Seventeenth Army was holding a small bridgehead. Here, too, the ground and the roads had been turned into quagmires by violent late-summer thunderstorms and torrential rain.

Nevertheless a temporary bridge was finished by noon of llth September. Parts of 16th Panzer Division crossed over. Throughout the night the division from Rhineland—Westphalia drove or marched through complete darkness and heavy rain over to the other bank. On the following morning at 0900 Hübe's tanks moved into the attack. Against a stubbornly resisting enemy the division gained 43 miles in 12 hours, over roads knee-deep in mud. It was followed by General Hubicki's 9th (Viennese) Panzer Division.

On 13th September the 16th Panzer Division stormed Lubny. The town was defended by anti-aircraft units and workers' militia, as well as formations of the NKVD, Stalin's secret police. The 3rd Company of the Engineers Battalion, 16th Panzer Division, captured the bridge over the Sula in a surprise coup. Using "Stukas on foot"— howling smoke mortars—they confused and blinded the Russians and in a spirited assault took the suburbs of the town. Behind them came the 2nd Battalion, 64th Rifle Regiment. Savage street fighting developed. The Soviet commander in the field had called the entire Russian civilian population to arms. Firing came from roofs and cellar windows. Behind barricades combat units armed with Molotov cocktails pelted the tanks. The eerie fighting continued throughout the day.

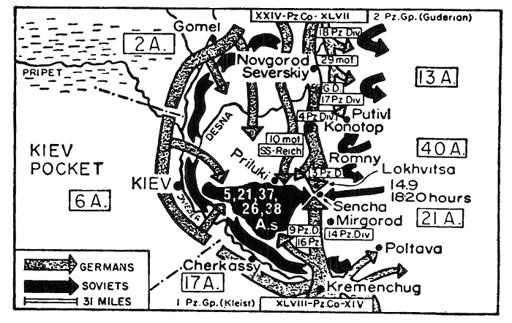

Map 7.

The battle of Kiev was a typical pincer operation with two armoured prongs. Guderian struck from thenorth, while Kleist moved in from the south. While the Russians were involved in heavy defensive fighting in the Dnieper bend, the German fast troops closed the trap behind them.

On 14th September, a Sunday, 79th Rifle Regiment joined action. In the afternoon Lubny was in German hands. By the evening the division's reconnaissance detachment was still 60 miles away from the spearheads of 3rd Panzer Division.

The Russians meanwhile had realized their danger. Aerial reconnaissance by the German Second and Fourth Air Fleets reported that enemy columns of all types were on the move from the Dnieper front against Guderian's and Kleist's formations, in the direction of the open gap. That gap had to be closed unless large parts of the Soviet forces were to get away.

Striking from the north, Guderian's divisions had taken Romny and Priluki. Model, with a single regiment, was struggling over muddy roads to Lokhvitsa. The rest of the division was still stuck in the mud a long way back. Major Pomtow, the chief of operations of 3rd Panzer Division, was tearing his hair.

There was still a gap of 30 miles between the two Panzer Groups. A 30-mile-wide loophole. Russian reconnaissance aircraft were circling over the gap, directing supply columns through the German lines. Hurriedly assembled groups of tanks were moving ahead to clear a path for them. General Geyr von Schweppenburg at his advanced battle headquarters suddenly found himself under attack by one of these Russian columns trying to break through the German ring. The headquarters turned itself into a strongpoint. An SOS was sent to 2nd Battalion, 6th Panzer Regiment. But they were still 12 miles away. In the nick of time Lieutenant Vopel's 2nd Company succeeded in snatching the general commanding XXIV Panzer Corps from almost certain death. The offensive towards the south continued.

The time was 1200 hours, the scene a muddy road near Lokhvitsa. "First Lieutenant Wartmann to the commander!" The order was passed on through the column. Wartmann, commanding a tank company, waded through the mud to the command tank of Lieutenant-Colonel Munzel, the new OC 6th Panzer Regiment. A quarter of an hour later the tanks started up their engines and the armoured infantry carriers of 3rd Platoon, 1st Company, 394th Regiment, under Sergeant Schroder, moved over to the right to make way for the tanks. The tankmen removed the camouflage from their vehicles: Lieutenant Wartmann was organizing a strong detachment for a reconnaissance towards the south. His orders were: "Drive through the enemy lines and make contact with advanced formations of Kleist's Panzer Group."

At 1300 hours the small combat group passed through the German pickets near Lokhvitsa. Stukas escorted them for a short distance. The sun shone down from a cloudless sky. The undulating country stretched far to the horizon. In front were the dark outlines of a wood. They had to pass through it. Suddenly a hastily retreating Russian column crossed their path—supply vehicles, heavy artillery, engineering battalions, airfield ground crews, cavalry units, administrative services, fuel-supply columns. The vehicles were hauled by tractors and horses. They carried drums of petrol and oil.

"Turret one o'clock. H.E. shells. Fire!" The fuel vehicles burned like torches. The horses broke loose. The Russians scuttled into the forest and behind the thatched farmhouses of a village. There was chaos on the road.

The German detachment moved on. Their job was not to fight the enemy, but to make contact with the forward units of Army Group South. They were still in radio contact with Division. There Major Pomtow was sitting next to the radio operator, intently following the recce unit's report on enemy dispositions, terrain, and bridges. Pomtow read: "Stiffening enemy opposition." Then there was silence. What had happened?

From Wartmann's tank, meanwhile, the situation looked like this. Horse-drawn carts and tractors were standing on the road, abandoned. Machine-gun and anti-tank fire was coming out of sunflower fields. Wartmann halted his tanks. He looked through his binoculars. A windmill on a near-by hill caught his attention. It was behaving rather strangely: one moment its sails would go round one way and then again the other way. Then they would stop altogether. Wartmann let out a soft whistle. Clearly an enemy observer was there, directing operations. "Tanks forward!" A moment later the 5-cm. shells slammed into the windmill. Its sails turned no longer. Forward.

Pomtow's radio operator, earphones clamped on his head, was writing: "1602 hours. Have reached Luka, having crossed Sula river over intact bridges." Pomtow was smiling. That was good news. Wartmann's detachment moved on

—through uncanny terrain with deep sunken lanes, swamps, and sparse forest. Whichever way he turned he saw enemy columns.

Wartmann's tanks had covered 30 miles. The day was drawing to its end. Suddenly radio contact was lost. Over to the south the silhouette of a town could be made.out against the evening sky. That no doubt was Lubny, the area where 16th Panzer Division was operating. They could hear the noise of battle. Evidently they had got close to the fighting lines of the southern front. But which way was the enemy? Was he in front or were they about to run into his flank?

Cautiously the armoured scout cars accompanying the tanks picked their way across a vast cornfield with the harvested grain piled in stocks. They dodged from one stock to the next. Suddenly an aircraft appeared overhead. "Look—a German reconnaissance plane!" "White Very light!" Wartmann commanded. With a whoosh the flare streaked up from the turret of the tank. White signals always meant: Germans here. A tense moment. Yes, the plane had seen it. He dipped down low. He circled. He circled again. "He's touching down!" And already the machine was rolling to a stop among the stooks in the cornfield—right among the enemy lines. There was much laughter and handshaking.

To-day nobody knows who the three resolute airmen were. They informed Lieutenant Wartmann about the situation on the front: less than six miles away were units of Kleist's 16th Panzer Division. A moment later the aircraft took off again. Wartmann's men could see it dip down low beyond the wide ravine, dropping a message.

Other books

Pink Slips and Glass Slippers by Hansen, J.P.

Ruby's War by Johanna Winard

Astonishing Splashes of Colour by Clare Morrall

Damn Him to Hell by Jamie Quaid

Nine Inches by Tom Perrotta

Dead Angels by Tim O'Rourke

The Use and Abuse of Literature by Marjorie Garber

The Viral Storm by Nathan Wolfe

The Battle by Barbero, Alessandro

50 Simple Soups for the Slow Cooker by Lynn Alley