Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (19 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

"It's still there!" Buchterkirch called out. Driver, radio-operator, and gunner all beamed. "Anti-tank gun by the bridge! Straight at it!" the lieutenant commanded. The Russians fled. Second Lieutenant Storck and his men leaped from their armoured carriers. They raced up on to the bridge. They overcame the Russian guard. There, along the railings, ran the wires of the demolition charges. They tore them out. Over there were the charges themselves. They pushed them into the water. Drums of petrol were dangling from the rafters on both sides. They slashed the ropes. With a splash the drums hit the water. They ran on—Storck always in front. Behind him were Sergeant Heyeres and Sergeant Strucken. Corporal Fuhn and Lance-corporal Beyle were dragging the machine-gun. Now and again they ducked, first on one side then on the other, behind the big water-containers and sand-bins.

Suddenly Storck pulled himself up. The sergeant did not even have to shout a warning—the lieutenant had already

seen it himself. In the middle of the bridge lay a heavy Soviet aerial bomb, primed with a time-fuse. Calmly Storck unscrewed the detonator. It was a race against death. Would he make it? He made it. The five of them combined to heave the now harmless bomb out of the way.

They ran on. Only now did they realize what 800 yards meant. There did not seem to be an end to the bridge. At last they reached the far side and fired the prearranged flare signal for the armoured spearhead. Bridge clear.

Buchterkirch in his tank had meanwhile driven cautiously down the bank and moved under the bridge. Vopel with the rest of the tanks provided cover from the top of the bank.

That was just as well. For the moment the Russians realized that the Germans were in possession of the bridge they sent in demolition squads—large parties of 30 or 40 men, carrying drums of petrol, explosive charges, and Molotov cocktails. They ran under the bridge and climbed into the beams.

Coolly Buchterkirch opened up at them with his machine-gun from the other side. Several drums of petrol exploded. But wherever the flames threatened to spread to the bridge squads of engineers were on the spot instantly, putting them out. Furiously, Soviet artillery tried to smash the bridge and its captors. It did not succeed. Störck's men crawled under the planking of the bridge and removed a set of charges—high explosives in green rubber bags. A near-by shell-burst would have been enough to touch them off.

Half an hour later tanks, motor-cycle units, and self-propelled guns were moving across the bridge. The much-feared Desna position, the gateway to the Ukraine, had been blasted open. A handful of men and a few resolute officers had decided the first act of the campaign against the Ukraine. Russia's grain areas lay wide open ahead of Guderian's tanks. Under a brilliant sunny late-summer sky they rolled southward.

Second Lieutenant Störck was just getting a medical orderly to stick some plaster on the back of his injured left hand when General Model's armoured command-vehicle came over the bridge.

The Second Lieutenant made his report. Model was delighted. "This bridge is as good as a whole division, Störck." At the same moment the Russian gunners again started shelling the bridge. But their gun-laying was bad, and the shells fell in the water. The General drove down the bank. Tanks of 1st Battalion, 6th Panzer Regiment, followed by 2nd Company, 394th Rifle Regiment, were moving into the bridgehead. The noise of battle in front grew louder—the plop of mortars and the rattle of machine-guns, interspersed by the sharp bark of the 5-cm. tank cannon of Lieutenant Vopel's 2nd Company. The Russians rallied what forces they could and, supported by tanks and artillery, threw them against the still small German bridgehead. They tried to eliminate it and recapture the bridge of Novgorod Severskiy— or at least destroy it.

But Model knew what the bridge meant. He did not need Guderian's reminder over the telephone: "Hold it at all costs!" The bridge was their chance of getting rapidly behind Buden-nyy's Army Group South-west by striking from the north. If Kleist's Panzer Group, operating farther south, under Rund-stedt's Army Group South, pushed across the lower Dnieper and wheeled north, a most enormous pocket would be formed, one beyond the wildest dreams of any strategist.

- The Battle of Kiev

Rundstedt involved in heavy fighting on the southern wing— Kleist's tank victory at Uman—Marshal Budennyy tries to slip through the noose—Stalin's orders: Not a step back!—Guderian and Kleist close the trap: 665,000 prisoners.

BUT where was Colonel-General von Kleist? What was the situation on Field-Marshal von Rundstedt's front? Where were the tanks and vehicles with the white 'K,' the mailed fist of Army Group South? What had been happening on the Southern Front while the great battles of annihilation were fought on the Central Front at Bialystok, Minsk, Smolensk, Roslavl, and Gomel?

What Smolensk meant for Army Group Centre, Kiev was to Army Group South. The Ukrainian capital on the right bank of the lower Dnieper, there about 700 yards wide, was to be captured following the annihilation of the Soviet

forces west of the river—in exactly the same way as Smolensk had been taken following the battle of encirclement in the Bialy-stok-Minsk area.

For Rundstedt's Army Group South, however, the plan did not go so smoothly as in the centre. There were several nasty surprises. Since, for political reasons, no operations were to be mounted initially on the 250 miles of Rumanian frontier in the Carpathians, the entire weight of the offensive had to be borne by the left wing—

-i.e.,

the northern wing—of the Army Group. There General von Stülpnagel's Seventeenth Army and Field-Marshal von Reichenau's Sixth Army were to break through the Russian lines along the frontier, to drive deep through the enemy positions towards the south-east, and then—with Kleist's Panzer Group leading—turn towards the south and encircle the Soviets, with Kleist's Panzer Corps acting as pincers. Or, rather, as one jaw of a pair of pincers. For, unlike Army Group Centre, Rundstedt had only one Panzer Group. The second jaw of the pincers, very much shorter, was to be provided by Colonel-General Ritter von Schobert's Eleventh Army, which was in the south of Rumania. This army was to cross the Prut and Dniester and drive to the east, in the direction of Kleist's armour—in order to close the huge pocket behind Budennyy's 1,000,000-strong Army Group.

It was a good plan, but the enemy facing Rundstedt was no fool. Besides, more important, he was twice as strong. Buden-nyy was able to oppose Kleist's 600 tanks with 2400 armoured fighting vehicles of his own—including some of the KV monsters. And he had entire brigades of the even more terrifying T-34.

On 22nd June the German divisions had successfully crossed the frontier rivers also in the south, and had pushed through the enemy's fortified positions along the border. But the planned rapid break-through on the northern wing did not materialize. To make a single Panzer Group the striking force for the conquest of so large and so well defended an area as the Ukraine had been a planning mistake. The rapid successes on the Central Front had been achieved by revolutionary tactical skill. There the two powerful Panzer Groups, boldly led, had encircled and liquidated the bulk of the Soviet defending forces. In the south and in the north, on the other hand, the absence of a two-pronged attack made it impossible to reach the intended targets. There simply were not enough armoured formations for the kind of vast- scale operation Hitler expected his armies in the east to perform along the entire front. Failure to reach the scheduled targets in the south was not due to any lack of skill on the part of the commanders, nor to any lack of courage, nor, least of all, to a lack of staying power on the part of the troops. It was simply due to the fact that there were too few armoured units—to a numerical shortage of the very service branch intended to carry the whole of Operation Barbarossa.

Not till after eight days of very heavy fighting, on 30th June, did the Soviet lines begin to waver. Rundstedt's northern wing rushed forward. But presently it was halted again by a new position—the hitherto unknown "Stalin Line." Heavy thunderstorms had turned the roads into quagmires. The tanks struggled forward. Bale after bale of straw was collected by the grenadiers from the villages and flung down in the mud. Even the infantry got stuck with their vehicles and made only very slow progress.

In the early light of 7th July Kleist's Panzer Group succeeded in penetrating the Stalin Line on both sides of Zvyagel. The llth Panzer Division under Major-General Crüwell pierced the line of pillboxes and fortifications in full depth and by a bold stroke took the town of Berdichev at 1900 hours. The Russians withdrew. But they did not retreat everywhere. The 16th Motorized Infantry Division got stuck in the line of pillboxes near Lyuban. There the Russians even counter-attacked with armour. General Hübe's 16th Panzer Division likewise encountered stiff resistance at Starokonstan-tinov. The troops ran out of ammunition. Transport aircraft had to bring up supplies for the tanks.

Bombers, Stukas, and fighter bombers of Fourth Air Fleet came to the division's assistance and smashed concentrations of Soviet armour. The combat group Hof er of 16th Panzer Division drove farther to the east and over-ran retreating artillery regiments. The 1st Battalion, 64th Rifle Regiment, experienced its most costly day of close combat at Stara Bayzymy. Within two hours the 1st Company lost three successive company commanders.

At long last, with the help of 21-cm. mortars, the bulk of 16th Panzer Division broke through the Stalin Line at Lyuban on 9th July. General Hube heaved a sigh of relief: only another 125 miles to the Dnieper.

The only pleasant feature of these weeks was the abundance of eggs. Early in July the division had captured an enormous Red Army food store with a million eggs. The quartermasters replenished their stocks. For a long time the

only worry of the NCO cooks was inventing new ways of serving eggs.

The officers at Divisional, Corps, and Army Group Headquarters had different worries. Anyone thinking that the crack units entrusted by Stalin with the defence of the Ukraine were on the point of collapse was soon disillusioned.

Defeated at one moment, they rallied again at the next. They hung on to their positions. They withdrew, and a moment later they stood and fought again. Fierce fighting flared up around Berdichev. The Russians used all the artillery they could lay hands on. The German artillery was completely smothered by the Soviet fire. Only by a supreme effort did Crüwell succeed in keeping them down with his reinforced llth Panzer Division. Things were similar throughout the southern sector. The Russians were indomitable. Rundstedt did not succeed in trapping Kirponos.

The fighting had been going on for over twenty days, and no decisive success had so far been achieved. There was some impatience at the Fuehrer's headquarters. Things were moving too slowly for Hitler. Suddenly he got the idea that "small pockets" would be a better plan. He therefore demanded that Kleist's Panzer Group should operate as three separate combat groups with the object of forming smaller pockets. One combat group was to form a tiny pocket near Vinnitsa, in conjunction with Eleventh Army coming up from the south.

Another group was to drive towards the south-east in order to cut off any enemy forces intending to withdraw from the Vinnitsa area. A third combat group, finally, was to drive towards Kiev, together with Sixth Army, and to gain a bridgehead on the eastern bank of the Dnieper.

Field-Marshal von Rundstedt emphatically objected to having his one and only Panzer Group split up in such a manner. This, he argued, was an unforgivable sin against the spirit of armoured warfare. "Operations in driblets won't give results anywhere," he telephoned to Hitler's headquarters. Hitler relented.

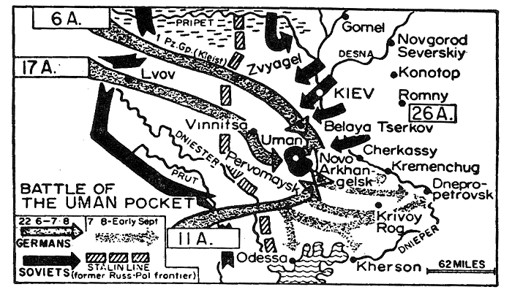

Map 6.

The battle of encirclement of Uman was developed with only one prong and in a fluid movement. Kleist's Armoured Corps circumnavigated twenty-five Soviet divisions and forced them against a wall of German infantry, composed of units of Sixth, Seventeenth, and Eleventh Armies. Three Soviet Armies were smashed.On the western bank of the Dnieper Kleist's Panzer Group pushed past Kiev towards the south-east with concentrated forces, and thus created the prerequisite either for describing a smaller arc towards Vinnitsa or a larger one towards Uman.

Everything was set for a small and for a large pocket south of Kiev. All the factors had been carefully taken into account, except one—Budennyy. The Marshal with the bushy moustache, who had been appointed Commander-in- Chief Army Group South-west Sector on 10th July, now played his final card. From the impenetrable Pripet Marshes, impassable to armour, he sent the divisions of his Fifth Rifle Army under Major-General Potapov against the northern flank of Reiche-nau's Sixth Army. These tactics, just as in the area of Army Group Centre, gave rise to severe and critical defensive fighting on Reichenau's left flank. But here, too, all went well in the end.

On 16th July Kleist's tanks reached the key centre of Belaya Tserkov. The first major battle of encirclement offered itself. Rundstedt wanted a large-scale outflanking movement and a big pocket. But Hitler ordered the lesser alternative, and for once he was right. A break in the weather favoured the movements of the Panzer divisions. Kleist struck accurately at the retreating enemy forces. On 1st August he reached Novo Arkhangelsk, and immediately moved on to attack Pervomaysk. Then he wheeled to the west and, in conjunction with the infantry divisions of Seventeenth and Eleventh Armies, closed the ring around the Russian forces in the Uman area.

It was not a huge pocket as at Bialystok, Minsk, or Smolensk. Nevertheless three Soviet Armies were smashed—the Sixth, the Twelfth, and the Eighteenth. The commanders-in-chief of the Sixth and Twelfth Armies surrendered. But 'only' 103,000 prisoners were taken as a result of this classical battle of encirclement with reversed front, fought under such exceedingly difficult conditions. Considerable enemy forces succeeded in breaking out, even though the 1st and 4th Mountain Divisions, as well as the 257th Infantry Division from Berlin, repeatedly tried hard to seal the gaps.

Major Wiesner's 1st Artillery Battalion, 257th Infantry Division, fired as accurately as if on the practice range and blasted column after column trying to break out of the pocket. The scale of the fighting is reflected in a single figure: the four guns of 9th Battery, 94th Mountain Artillery Regiment, fired 1150 rounds during the four days of the battle of Uman. That was more than the total rounds fired by the battery throughout the campaign in France. The enemy weapons destroyed or captured testified to the fierceness of the fighting: 850 guns, 317 tanks, 242 anti-tank and anti- aircraft guns were abandoned by the Russians on the battlefield.

Yet the significance of the battle of Uman considerably surpasses these numerical results. The strategic implications of the victory won by Army Group South were considerably greater than the number of prisoners suggested.

The road to the east, into the Soviet iron-ore region of Krivoy Rog and to the Black Sea ports of Odessa and Niko- layev, was open. Above all, Kleist's Panzer Corps was now able to push through to the lower Dnieper and to gain the western bank of the Dnieper bend from Cherkassy to Zaporozhye. This move, moreover, offered the chance of a great battle of annihilation around Kiev—a chance which so mesmerized Hitler that he halted Army Group Centre's offensive against Moscow and diverted Guderian's tanks to the south, towards Kiev. These two great armoured prongs were now to embark on a new gigantic battle of encirclement against the Soviet South-west Front with its one million men.

On 29th August Guderian's Fieseier Storch aircraft took off from Novgorod Severskiy and described a bold arc over the Russian front. Above the Russian lines, right on top of Yere-menko's divisions attacking the German bridgehead, he dipped down low, then banked, and across the Desna returned to Unecha, to Panzer Group headquarters. The time was just before 1800.

Guderian had been to see his 3rd and 4th Panzer Divisions which were trying to extend their bridgehead in order to continue their thrust to the south. But the troops were pinned down. He had also been to XLVI Corps, whose 10th Motorized Infantry Division and 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions were busy repelling fierce Soviet attacks from the flank. The situation there was not too rosy either. Too much was being demanded of the men. They were short of tanks and short of sleep.

Next to Guderian sat Lieutenant-Colonel Bayerlein, the situation map spread out on his knees. Thick red arrows and arcs on the map indicated the strong Russian forces in front of the German spearheads and along their flanks. "Yeremenko is going all out to reduce our bridgehead," Guderian was thinking aloud. "If he succeeds in delaying us much longer, and if the Soviet High Command discovers what we are trying to do to Budennyy's Army Group, the whole splendid plan of our High Command could misfire."

Other books

Rebel Roused (Untamed #5) by Victoria Green, Jinsey Reese

Undue Influence by Steve Martini

Nan Ryan by The Princess Goes West

Forest Fire by J. Burchett

Tug by K. J. Bell

Dead In The Hamptons by Zelvin, Elizabeth

Survival by Piperbrook, T.W.

Promises After Dark (After Dark #3) by Kahlen Aymes

All She Ever Wanted by Barbara Freethy

The Sanctuary by Arika Stone