Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (22 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

To return to the battle. One might have expected that Guderian's offensive on the Bryansk flank would encounter a well-prepared opponent and therefore stiff resistance. After all, General Yeremenko had begun building up his famous

front as early as 12th August, immediately after his conversation with Stalin, when an attack seemed imminent, and he had been reinforcing it ever since.

To this day Marshal Yeremenko maintains in his memoirs that at the end of August Guderian could never have broken through his defensive front, and that his drive to the south, to Kiev, had essentially been a second-best choice. For the fox Guderian the grapes of Moscow had hung too high: that was why he had gone to Kiev instead. Strangely enough, they were now, six weeks later, very much within his reach. Boldly and unconcernedly Guderian reached out for them by his drive to Bryansk, the important rail and road junction.

Even at the time of Guderian's drive into the Ukraine, in August, the town of Bryansk had been a kind of mysterious and sinister threat in his flank. It was known, from the evidence of prisoners, that General Yeremenko and his staff resided there, together with special contingents and crack units. It was known that the town was a key point in the Soviet defence of Moscow. It lay embedded in thick forests, protected by swampy lowlands. From it attacks were launched repeatedly against Guderian's exposed flank. And now that the decisive blow at Moscow was beginning to take shape from the Roslavl-Smolensk area, Bryansk and the Soviet armies in its vicinity again represented a grave threat to Guderian's flank. To remove this threat was as much a prerequisite for the main attack on Moscow as was the liquidation of the strong covering forces in the Vyazma area.

That was the tactical meaning of the double battle of Vyazma and Bryansk.

To every one's surprise Guderian's attack against Yere-menko's defensive front succeeded at the first attempt. The break-through was accomplished in the area of the Soviet Thirteenth Army.

It was fine autumn weather. The roads in the area of Second Panzer Group were still dry. The spearhead of XXIV Panzer Corps, the 4th Panzer Division, raced ahead as if the devil were at their heels. As he was chasing after his advanced detachment—already being led against Dmitrovsk-Orlovskiy by Major von Jungenfeldt—Guderian met the Corps commander and the commander of 4th Panzer Division, Generals Freiherr Geyr von Schweppenburg and Freiherr von Langermann-Erlenkamp. The great question was: should the advance be continued in order to knock out completely the Soviet Thirteenth Army, which was already in confusion, or should the troops be halted and given time to re-form and stock up with fuel? Both generals counselled caution: they had been getting reports that fuel was running short and that the men were tired out.

A little later, near the windmill hill of Sevsk, Guderian met Colonel Eberbach, the commander of the Panzer brigade. "I hear you're forced to halt, Eberbach," said Guderian. "Halt, Herr Generaloberst?" the colonel asked in surprise. He added drily: "We're just going nicely, and it would be a mistake to halt now." "But what about the juice, Eberbach? I'm told you're running out." Eberbach laughed. "We're running on the juice that hasn't been reported to Battalion." Guderian, who knew his men, joined in the laughter. "All right, carry on," he said.

That day the tanks of 4th Panzer Division covered 80 miles, fighting all the way. The Soviet Thirteenth Army was completely dislodged. What Yeremenko had thought impossible happened: the town of Orel, 12 miles behind the Bryansk front, was taken by Eberbach's tanks at noon on 3rd October. The pickets outside the town were taken so much by surprise that they did not fire a single round. The first vehicle the German tanks encountered was a tram full of people. The passengers clearly thought that Soviet troops were moving into the town and waved delightedly.

Things were now going badly for Yeremenko's Bryansk front. The 17th and 18th Panzer Divisions of XLVII Panzer Corps wheeled towards Karachev and cut the Bryansk-Orel road behind Yeremenko's headquarters. On 5th October the 18th Panzer Division took Karachev. The trap was closing. Yeremenko saw the impending disaster. He telephoned the Kremlin and asked for permission to break out. But Shaposh-nikov, the Chief of General Staff, put him off. He urged him to wait a little longer.

Yeremenko waited.

But Guderian's armoured spearheads did not.

With an advanced detachment of the reinforced 39th Panzer Regiment Major Gradl struck towards Bryansk from

Karachev—that is, from behind, 30 miles past Yeremenko's headquarters. And on 6th October General von Arnim's 17th Panzer Division did what not even the greatest optimist would have considered possible: they took the town of Bryansk and the bridge over the Desna by a swift coup. Bryansk was taken. The town crammed full with troops, heavy artillery, and police units had quite simply fallen. In vain were 100,000 Molotov cocktails lying in the stores. In vain had the strict order been issued: not a single house to be surrendered without opposition. One of the most important railway junctions of European Russia was in German hands. The link-up between Guderian's Second Panzer Group and the Second Army, which was coming up from the west, had been accomplished. Around Karachev and north of it the 18th Panzer Division and, subordinated to it, the "Grossdeutschland" Motorized Infantry Regiment were providing cover. Farther south, to both sides of Dobrik, the 29th Motorized Infantry Division was covering the Corps' flanks. The trap had been closed behind three Soviet Armies—the Third, the Thirteenth, and the Fiftieth. The date was 6th October.

During the following night the first snow fell. For a few hours the vast landscape was shrouded in white. In the morning it thawed again. The roads were turned into bottomless quagmires. The great highways became skid-pans. "General Mud" took over. But he was too late to save Stalin's armies in the Vyazma—Bryansk area. Entire infantry divisions were detailed for road-clearing. They worked like men possessed in order to keep the advance going.

Farther north, along the Smolensk-Moscow highway, the offensive had likewise started successfully. Hoepner's Fourth Panzer Group sluiced three Panzer Corps—XL, XLVI, and LVII Corps—through the Soviet front south of the

highway at Roslavl behind the 2nd Panzer Division. They fanned out and with their left wing thrust northward in the direction of the motor highway.

On 6th October the spearhead of 1 Oth Panzer Division was only 11 miles south-east of Vyazma, skirmishing with retreating Soviet units. The battle of Vyazma had reached its peak. During the night there was a succession of Soviet attempts to break out of the ring. At nightfall the whole vast forest area seemed to come to life. Firing came from everywhere. Ammunition was blowing up. Ricks of straw were blazing. Signal flares eerily lit up the scene for a few seconds. The area swarmed with Red Army soldiers who had lost their units. The advance command post of XL Panzer Corps had to fight for their lives. Where was the front line? Who was surrounding whom? When the long night at last drew to its end a Soviet cavalry squadron tried to break through in the grey light of dawn of 7th October.

Behind it came a convoy of lorries carrying Red Army women. Machine-gun positions of 2nd Panzer Division foiled the attempted break-out. It was a painful and sickening picture—horses and their riders collapsing and dying under the bursts of machine-gun fire.

In the morning of 7th October the most forward parts of General Fischer's 10th Panzer Division penetrated through the slush into the suburbs of Vyazma and finished off Soviet resistance inside the burning town. Beyond the northern edge the men of the 2nd Battalion, 69th Rifle Regiment, crawled into the abandoned Russian fox-holes. The spearheads of General Stumme's XL Panzer Corps, followed by 2nd Panzer Division and 258th Infantry Division, had thus reached the objective of the first phase of the operation.

South of them followed XLVI Panzer Corps under General von Vietinghoff, with llth and 15th Panzer Divisions as well as 252nd Infantry Division. Behind them, in turn, were LVII Panzer Corps under General Kuntzen with 20th Panzer Division, the "Reich" Motorized SS Infantry Division, and the 3rd Motorized Infantry Division.

Hoth's two Panzer Corps—LVI and XLI Corps—and VI Infantry Corps, having broken through on high ground west of Kholm, encountered very stiff resistance north of the Moscow highway from several well-dug-in infantry divisions as well as Russian armoured brigades. Because of the extremely unfavourable terrain Colonel-General Hoth united the tanks of LVI Panzer Corps—most of them Mark Ills— into the "Panzer Brigade Koll," which after fierce fighting pierced the Soviet positions on the Vop along a firm causeway made from branches and planks thrown into the mud. Following behind, XLI Panzer Corps provided cover for the northern flank by attacking Sychevka with 1st Panzer Division and 36th motorized Infantry Division.

Meanwhile the 6th and 7th Panzer Divisions reached the undamaged Dnieper bridges at Kholm, and likewise wheeled round towards Vyazma. In the evening of 6th October the battle-hardened 7th Panzer Division, Rommel's old striking force from the French campaign, was on the Moscow highway behind the enemy's rear, facing west for the third time

in fifteen weeks. On 7th October Hoth's tanks linked up with Hoepner's in Vyazma. The pocket around six Soviet Armies with 55 divisions was closed.

Simultaneously with the breakthrough towards Vyazma, von Manteuffel's combat group had reached the Moscow highway by a surprise advance and cut it. Field-Marshal von Brau-chitsch, Commander-in-Chief of the Army, thereupon sent a signal to the division: "I express my special commendation to the splendid 7th Panzer Division which by its swift advance to Vyazma has, for the third time in this campaign, made a major contribution to the encirclement of the enemy."

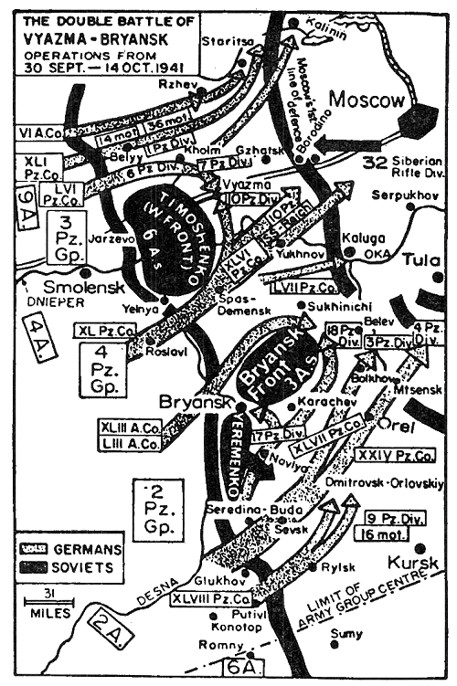

Map 8.

The double battle of Vyazma and Bryansk was a perfect pincer operation. The jaws of the pincers were formed by the fast formations of three Panzer Groups. Infantry divisions of three Armies co-operated. Theforces defending the Soviet capital were encircled and smashed: the road to Moscow was clear.

At Bryansk also, Guderian's two Corps had meanwhile trapped Yeremenko's three Armies of 26 divisions in a northern and a southern pocket. Now followed difficult days for the infantry—opposing fierce Russian attempts to break out of the pockets, splitting up the pockets, reducing individual strongpoints, and dealing with prisoners as, towards the end, the Soviets surrendered in entire regiments. The fighting continued until 17th October. Naturally, parts of the trapped forces succeeded in breaking out, especially from the southern pocket at Bryansk. Among those who succeeded were General Yeremenko and his staff. Yeremenko himself was seriously wounded and had to be flown out by aircraft.

The great battle was over. The first act of Operation Typhoon had been played out. Some 663,000 prisoners had been taken, and 1242 tanks and 5412 guns destroyed or captured.

Only three weeks after the battle of Kiev, when half a dozen Soviet Armies of Budennyy's Army Group had been crushed in the south and more than 665,000 Soviet troops taken prisoner, another vast fighting force of nine Armies with 70 to 80 divisions and brigades had now been annihilated on the Central Front.

These were the Armies which were to have protected Moscow. In endless, pitiful columns they were now trudging into captivity over the muddy roads. Moscow had lost its shield and its sword. A wide gap had been torn in its defences. The German Army Group Centre had gained freedom of manœuvre for the bulk of its armoured and motorized formations against Stalin's capital. The second phase of Operation Typhoon could now begin—the pursuit of the enemy right into the city. Tank rally in Red Square!

On they drove. Or, rather, they did not drive—they struggled through the mud. Entire companies were pulling bogged- down lorries out of the mud of the roads. The motor-cyclists made wooden skids for their machines from boards and planks and pulled them along behind them.

Major Vogt, commanding the support units of 18th Panzer Division, was in despair. How did the Russians manage with these muddy roads year after year? He hit on the answer. He got hold of the small tough horses he had seen the local peasants use, as well as their light farm-carts, and used them for sending his divisions' supplies forward, a few hundredweight on each cart. It worked. The motorized convoys were stuck in the mud, but the small peasant carts got through. The prize of Moscow spurred the men to a supreme effort.

Other books

Taken By Him (Obsessed With Him, Book Four) by Hannah Ford

Witcha'be by Anna Marie Kittrell

The Black Hearts Murder by Ellery Queen

Badlanders by David Robbins

The Portal (Novella) by S.E. Gilchrist

The Loblolly Boy and the Sorcerer by James Norcliffe

Surfacing by Margaret Atwood

Saint Anything by Sarah Dessen

As Sweet as Honey by Indira Ganesan

Soul Mates Kiss by Ross, Sandra