Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (67 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Nehring stood in front of the situation map, studying the red arrows and loops in the notorious 50-mile breach in the front between Kaluga and Belev—the breach which had been the nightmare of all headquarters personnel for the past fortnight.

"And what is to happen?" Nehring asked.

Liebenstein answered, "We've no other choice but to detach units from our Orel front, hard-pressed though we are ourselves, in order to stabilize the situation in the gap. We must link up with Gilsa again and strengthen his defensive front. And that is where you come in with your well-tried 18th. Needless to say, you'll be given some further forces, to be put under your command. We have in mind 12th Rifle Regiment, 4th Panzer Division, and Major-General von Scheele's 208th Infantry Division, which has just arrived from France and is at present employed as flank cover south of Belev. Admittedly, we've taken 309th and 337th Infantry Regiments away from the division because they were urgently needed by Ninth Army in the Sychevka area."

Nehring, an experienced commander in many critical situations, was not exactly pleased with the assignment. But he realized the need for the action.

The regiments took ten days to cover the roughly 125-mile journey from their sector via Orel, Bryansk, and Ordzhonikid-zegrad to the assembly area near Zhizdra. Their journey in a temperature of 40 degrees below zero, through three-foot-deep snow and mountainous drifts, was sheer hell.

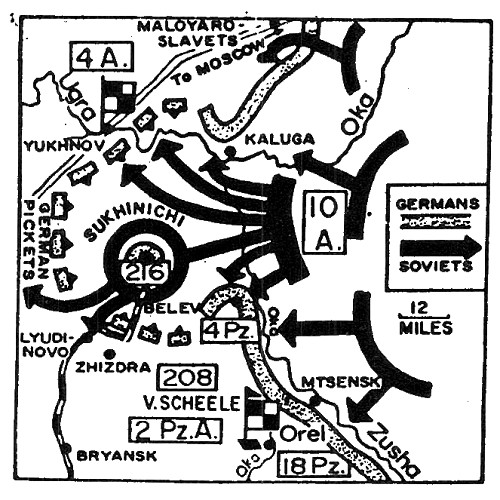

Map 21.

The Soviet break-through between Fourth Army and Second Panzer Army in January 1942. Sukhinichi acted as a breakwater behind the breached front.

Captain Oskar Schaub from Vienna, a battalion commander in 12th Rifle Regiment, has described the way the units struggled through open country. The narrow wheels of guns and supply vehicles, he recalls, sank into the snow up to their axles. Lorries kept getting stuck. On the whole, the horse-drawn units managed best. The tough little farm-horses averaged about three miles an hour with their carts or sledges. The motorized troops with their tracked and wheeled vehicles managed barely more than a mile—half as much as a pedestrian would cover under normal conditions. The horse, in fact, was greatly superior to motor vehicles and armour in these conditions. The result was that all Panzer

divisions were equipping themselves with horses during the winter.

On 16th and 17th January the reinforced 18th Panzer Division got ready to move off from Zhizdra. Its left wing was covered by 12th Rifle Regiment under Colonel Smilo von Lüttwitz, while the right flank was protected against enemy surprise attacks by units of 208th Infantry Division. Strong patrols on skis screened the area of the advance. Makeshift snow-ploughs cleared the road for the marching columns. Operation Sukhinichi got going. It was one of the most extraordinary, harebrained, and risky operations of the winter war.

Nehring's present comment is: "A piece of strategic impertinence."

He was right. In the Sukhinichi area there were no fewer than thirty Soviet rifle divisions operating, as well as six rifle brigades, four armoured brigades, two air-borne brigades, and four cavalry divisions. That was a truly gigantic force— an elephant about to be attacked by a mouse.

However, cunning, skill, and daring succeeded in out-manceuvering the Russians. The mouse slipped into the elephant's trunk.

Colonel Kuzmany, the one-armed Austrian commander of 338th Infantry Regiment, was standing up on his little peasant sledge. He was driving at the head of his combat group. Under him were three battalions, reinforced by tanks and artillery. His thrust was in the middle of the attack, via Bukan and Slobodka towards Sukhinichi. Colonel Jolasse, commanding 52nd Rifle Regiment, cleared some elbow-room for Kuzmany on the left flank and in the rear, and with his combat group attacked the strongly defended township of Lyu-dinovo. His force consisted of two battalions, the Panzer Company von Stunzner, the 2nd Company Panzerjäger Battalion 88, and a battery of 208th Artillery Regiment. The Russians were completely taken by surprise: they had not expected an attack so far from the fighting-line by German forces emerging like phantoms from the snowy wastes.

The companies of Jolasse's combat group dislodged the enemy from Lyudinovo and chased him into the forests and the snow-covered lake district. In ferocious street fighting against Soviet emergency units the battalions Wolter and Aschen cleared a road through the town. This first engagement yielded a considerable quantity of captured weapons, 150 prisoners, and over 500 killed.

Kuzmany meanwhile also battered his way through a surprised enemy. Wherever the Russians attempted to offer resistance they were smashed by concentrated fire from all weapons.

First Lieutenant Klauke, commanding 2nd Battery, 208th Artillery Regiment, stood on a sledge directing the fire of field howitzers. Attacking battalions were dispersed and machine-gun and mortar positions smashed at point-blank range.

There was no time for the gunners to aim their guns by calculation. "A quick look through the barrel, and you knew the direction was all right" is how Corporal Werner Bur-meister, a gun-layer in 2nd Battery, recalls the situation.

Colonel von Lüttwitz meanwhile with his reinforced 12th Rifle Regiment was working his way forward in the deep western flank of Nehring's formations. Captain Schaub records in his report of engagement: "The wheels kept getting stuck in the chest-deep snow. Working till late at night, the 2nd Company shovelled their way through to a signal-box on the Ordzhoni-kidzegrad-Sukhinichi line. The temperature was 40 degrees below. Rifles and machine-guns had to be wrapped up as carefully as the men's noses and hands, or else the oil would freeze—and that could be fatal."

Every yard of their way had to be shovelled clear. And at any moment the enemy might appear from the right, from the left, from behind or from in front. Out of this situation Lüttwitz evolved a novel fighting method. Schaub describes it as follows: "The point company would struggle through the deep snow along both sides of the road to the nearest village and attack the enemy in this narrow deep formation, working like an assault detachment. The attack would be opened with concentrated mortar-fire. After that the hand-grenade was the principal weapon—or, at close quarters, the trenching-tool. Meanwhile the remaining companies would shovel the road clear for the motor vehicles. Thus our combat group resembled a slowly moving hedge-hog."

The front line was everywhere. Even the divisional headquarters personnel had to fight for their lives on 20th January,

when, late in the evening, a Russian battalion charged Slobodka in the snowy light. They were saved by a 2-cm. AA gun of the headquarters security detachment until the sapper battalion hurried to the scene to retrieve the situation.

Thanks to this bold improvisation and the continuous alternation of attack and defence, advance, flank-screening, and rear cover, "Operation Sukhinichi" succeeded. Two weak divisions had slashed a 40-mile-long corridor right through an enemy Army, to reach a besieged strongpoint.

On 24th January at 1230 hours Colonel Kuzmany shook hands with a battle outpost of the combat group under Freiherr von und zu Gilsa. A bridge had been built to the cut-off 216th Infantry Division and the formations subordinated to it. It was a narrow bridge, but it held.

The following morning Nehring drove into the town to discuss the situation with Gilsa. A thousand wounded were lying in the cellars of the ruined houses: to get them out was one of the most urgent tasks. This, like everything else about this operation, was done in an unconventional way. Five hundred local sledges with Russian peasants and prisoners as drivers were available in Lyudinovo. Each sledge could accommodate only one wounded man. Every driver, therefore, had to make the 40-mile trip through no-man's-land four times. But not a single one dropped out. Every one of them stood up to the tremendous demands made by the night-time sleigh-ride through biting frost, blizzard, and enemy patrols.

In command of this mercy fleet was a corporal—a village priest in civilian life. His assistant was a cavalry sergeant. Their helpers were 500 Russians. The two Iron Crosses which Nehring had earmarked for them were never awarded: the two good Samaritans disappeared in the turmoil of battle. Their names are not known.

The importance of Operation Sukhinichi in the general situation is reflected by the fact that Hitler paid tribute to it in a special announcement. This was his way of demonstrating that surrounded units which obeyed his order and held on as breakwaters regardless of being bypassed by the enemy would not be forgotten. This demonstration was an important prerequisite for the troops' perseverance at other points of the front where major or lesser formations were encircled, as, for example, at Kholm and Demyansk.

"They'll get us out": this unshakable belief of surrounded troops and their officers was justified time and again during that winter of 1941-42. It is a point that must be remembered by all those who to-day shake their heads in uncomprehending amazement at the blind faith shown a year later by the encircled German Sixth Army at Stalingrad.

Sukhinichi was a decisive strategic success. Nevertheless, in a sound appreciation of the situation, Lieutenant-General Freiherr von Langermann-Erlenkamp, commanding XXIV Panzer Corps, decided to evacuate the exposed town of Sukhinichi itself. This move made it possible to establish a more favourable defensive front across that notorious breach which was now being closed again. The nightmare of the German High Command was at an end. Conditions had been created for smashing the southern prong of the Soviet offensive.

After weeks of heavy fighting, lasting well into the spring, the bulk of the divisions of the Soviet Tenth and Thirty- third Armies, the I Guards Cavalry Corps, and the 4th Parachute Commando which had penetrated, were annihilated south-east of Vyazma. That was the great battle in the Ugra bend, with its focal points at Ukhnov, Kirov, and Zhizdra. In this battle downright superhuman feats were performed by the divisions from Brandenburg and Bavaria, from Schleswig-Holstein and Mecklenburg, the Upper Palatinate and Hanover, from Hesse and Saxony, as well as by the independent 4th "Death's Head" SS Regiment and the Parachute Assault Regiment Meindl.

What this savage fighting looked like from the other side is revealed by two impressive documents—both of them captured diaries of Soviet officers. They afford a glimpse of the morale of the Russian front-line troops in the Sukhinichi-Yukhnov-Rzhev area.

The first diary is that of Lieutenant Goncharov, a company commander and temporary battalion commander in 616th Rifle Regiment. He was killed in action north-west of Yukhnov on 9th February 1942.

The second diary is that of a lieutenant of 385th Rifle Division whose name had been proposed for the title of "Hero of the Soviet Union." Since it is not certain whether he is alive, his name shall not be given here. Both diaries are extant

in the original and come from the archives of the Intelligence Officer of the German XL Panzer Corps.

Goncharov's notes reveal a simple soul-a man who believed in Stalin's political slogans, was annoyed with his superiors, and passed on all kinds of front-line gossip. The entries are revealing in many ways:

2nd January 1942. When the 4th Battalion withdrew from Yerdenovo we had to leave our dead and wounded behind. The wounded were killed by the Germans.

5th January 1942. I talked to the civilian population about the Germans. Generally speaking, they all tell the same tale— looting, executions, rape. But it strikes me that they relate these fascist atrocities without revulsion. They talk about them just as though they are reporting a lecture by the collective farm chairman. And yet, how revolting is everything about that Aryan race! No sense 'of decency. They strip themselves naked in the presence of women and kill their lice. We have always regarded the Aryans as people of culture. Now it is clear that these Aryans are dull, stupid, shameless bourgeois.

10th January 1942. I have read Molotov's note to-day about the German atrocities. One's hair stands on end when one reads the few examples listed. In my opinion the world has not room enough for retribution for all that this Nordic race has inflicted on us. But we shall have our revenge—we shall have it of their whole race—in spite of our very humane and moderate leader Stalin. To hell with international considerations! Sooner or later we shall have to fight England as well.

Other books

Bend Me, Break Me by Cameron, Chelsea M.

Urban Assassin by Jim Eldridge

Damned: Seven Tribesmen MC by Glass, Evelyn

The Devils Novice by Ellis Peters

Scandalous by Melanie Shawn

Earth and High Heaven by Gwethalyn Graham

La sangre de los elfos by Andrzej Sapkowski

Götterdämmerung by Barry Reese

Shadow Man by Grant, Cynthia D.

Hell Fire by Aguirre, Ann