Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (69 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

But the attack they had repulsed at the mouth of the Tigoda was not the expected Soviet full-scale attack. During those first few days of the New Year there was fierce local fighting everywhere between Kirishi and Novgorod. The Russians were prodding the Volkhov front to find its weak points; they were carrying out reconnaissance in force to identify German positions and units; they were searching for a gap through which they could thrust. The old-timers could feel it in their bones: something was in the air, a large-scale attack was imminent. When would it come? And where? Those were the agonizing questions.

Major Rüdiger, commanding the Intelligence detachment of 126th Infantry Division, heaved a sigh of relief when a monitoring company NCO knocked at his door late in the evening of 12th January and brought him an intercepted and decoded signal from the Soviet Fifty-second Army to its 327th Rifle Division: "Positions to be held at all costs.

Offensive postponed. Continue feinting attacks."

So there was not going to be an offensive after all—at least not in this sector, Rüdiger concluded. He immediately rang up Lieutenant-General Laux, his C.O. Laux, an experienced officer, thanked him for the information, but added, "I wouldn't trust those fellows too far."

The contents of the intercepted radio signal soon spread about. When, therefore, Soviet artillery started shelling the German positions over a broad front at 0800 hours on the following morning, 13th January, the troops did not take it too seriously.

But after a while things began to look suspicious. The heavy bombardment did not look like a blind. The guns then lengthened their range beyond the German lines. The time was 0930. Under the massive artillery umbrella numerous

packs of infantry emerged from the haze of the dawning winter day, and ski detachments came gliding over the ice of the Volkhov. "The Russians are coming!"

The radio signal of the night before had been a Soviet ruse to deceive the German command. The battle of the Volkhov had begun: it had started north of Novgorod, at the junction between 126th and 215th Infantry Divisions.

By 1030 hours the Soviets had established their first bridgehead across the Volkhov at Gorka, in the sector of 422nd Infantry Regiment, and had broken into the German main fighting-line.

Colonel Harry Hoppe, the conqueror of Schlüsselburg, mounted an immediate counter-attack with units of 424th Infantry Regiment and sealed off the penetration. But he did not succeed in regaining the old main fighting-line.

In the morning of 14th January the enemy attacked again, and strong formations succeeded in infiltrating through the snow-bound forests into the rear of the German positions. By nightfall the spearheads of fast Soviet ski battalions stood in front of the gun emplacements of the divisional artillery. The German gunners defended themselves with trenching-tools, carbines, and pistols and repulsed the Soviets. But for how long?

While Division and Corps were still convinced that the main weight of the Soviet attacks was in the sector of 422nd Infantry Regiment, a far greater disaster was unrolling farther north, in the Yamno-Arefino area. It was there, at the junction between 126th and 215th Infantry Divisions, where the sectors of the two wing regiments, 426th and 435th Infantry Regiments, abutted, that the Soviets had concentrated their main effort.

On a very narrow front, therefore, the crack Soviet 327th Rifle Division and the superbly equipped independent 57th Striking Brigade charged across the Volkhov against the positions of the three weakened battalions of a single German regiment—426th Infantry Regiment under Lieutenant-Colonel Schmidt.

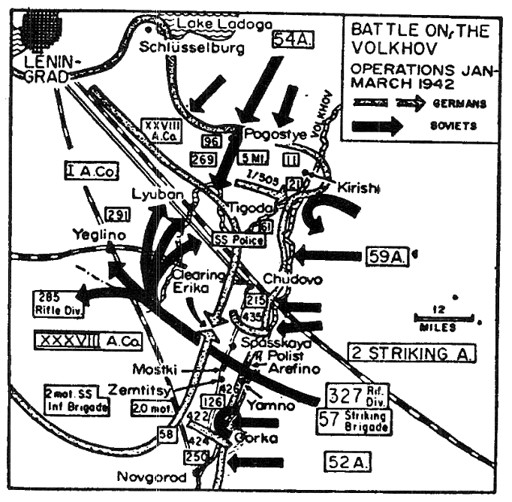

Map 22.

The Volkhov battle and the operations from the beginning of January to the end of March 1942. The bulk of the Soviet Second Striking Army, having broken through the German front, was pinched off at the clearing "Erika."

Simultaneous Soviet attacks on 435th Infantry Regiment, lying on the left of the 426th, prevented help being sent from there. Skilfully takieg advantage of deep hollows in the ground in front of the German main fighting-line, the Soviets punched their way into the German positions, cracked the line of strongpoints, and, with the bulk of XIII Cavalry Corps of the Second Striking Army, swept like a tidal wave through the burst dike into the hinterland. Ceaselessly the Russians pumped reinforcements through the two-to-three-mile gap and pressed on towards the Novgorod-Chudovo road.

In a cutting cold of 50 degrees below zero the dispersed German companies hung on to clearings in the woods and to high snowdrifts and made the Soviets pay heavily for their slow advance. It took the Russians four days to cover the five-mile distance to the road. And when they did reach the road they had not gained much, for three German strong- points continued to hold out firmly along it like pillars against the battering waves—Mostki, Spasskaya Polist, and Zemtitsy.

Surrounded by the enemy, these strongpoints held on for weeks in the rear of the Soviet flood. They became focal points in the fighting for the vital road, the north-south link of the Volkhov front.

By 24th January the Russians had pumped sufficient forces into the penetration to launch their drive in depth. With cavalry, armour, and ski battalions they raced boldly through the narrow—in fact, all too narrow—bottleneck towards the north-west. It was a perfect breakthrough. But its basis was dangerously narrow.

What were the Russians after? Were their operations aimed against Leningrad, or did they have other, more far- reaching intentions? That was the question agitating the German Staff. They did not have to worry their heads very long. After eight days the spearheads of the Soviet assault regiments were already 55 miles behind the German front. If they were aiming at Leningrad they had covered half the distance.

On 28th January Russian forward detachments attacked Yeglino. The direction of the attack, therefore, was towards the north-west, bypassing Leningrad in the South, towards the Soviet-Estonian frontier. We know to-day that the big drive outflanking Leningrad was in fact originally intended to go as far as Kingisepp—a more than optimistic idea. But then the Russians suddenly stopped at Yeglino and, instead of continuing westward, swung north-east towards Lyuban, on the Chudovo—Leningrad road. Were they aiming at Leningrad after all?

General of Cavalry Lindemann, who had succeeded to the command of Eighteenth Army when Field-Marshal von Küchler took over Army Group North on 15th January, needed only one glance at the large situation map in order to read the Russian intentions. Their penetration area, the bottleneck through which they were pouring, was too narrow and their exposed flanks were too long. To advance farther would have been foolhardy.

Since the Soviet Fifty-fourth Army was just then attacking the German 269th Infantry Division at Pogostye, south of Lake Ladoga, the Russian intentions were clearly revealed by the map: to begin with, the German I Corps was to be annihilated in a pincer operation.

"We must be prepared for anything and not lose our nerve," remarked General of Infantry von Both, commanding the East Prussian I Corps in Lyuban, as the commander of the Corps headquarters started issuing carbines and machine pistols to the officers and clerks. Not to lose one's nerve— that was the problem.

The 126th Infantry Division has been severely blamed for allowing the Russians to break through in its sector. That is unfair. No regiment of any other weakened division on the Eastern Front could have held this concentrated Soviet attack. In judging the 126th Infantry Division one should remember not so much the Soviet break-through as the fact that this division continued to hold the flanks and cornerstones of this barely 20-mile-wide gap day after day against the onslaught of Soviet combat groups, and by doing so prevented the penetration from being widened.

In spite of continuous costly attacks the Russians did not succeed in widening their narrow corridor. They left some 15,000 dead in front of the positions of 126th Infantry Division. This circumstance presently had dramatic consequences.

It was Colonel Harry Hoppe, the hero of Schlüsselburg, and his 424th Infantry Regiment who enabled a new main fighting-line to be established along the southern edge of the penetration.

The northern edge was held with admirable steadfastness by the 215th Infantry Division under Lieutenant-General Kniess. A vital contribution was made by the stubborn defence of the strongpoints Mostki, Spasskaya Polist, and Zemtitsy. There the "Brigade Köchling," an

ad hoc

collection of units from fifteen different divisions, defended the strongpoints throughout, many weeks.

Exemplary resistance was offered in Zemtitsy by Captain Klossek with his 3rd Battalion, 422nd Infantry Regiment. If any proof was needed that Hitler's blunt and uncompromising hold-on order and its self-sacrificing observance by the men could in certain conditions avert disaster and create the prerequisite for future successful operations, then this proof was supplied by the battle on the Volkhov.

Some 125 miles away from the Volkhov front, meanwhile, the 58th Infantry Division from Lower Saxony was still holding the Leningrad suburb of Uritsk—the same division which nearly six months previously had reached the first tram-stop of Leningrad and thus, virtually, the cradle of the Red revolution.

"All unit commanders to report to Divisional HQ at 1100 hours for a conference!" Telephones rang. "Conference with the General," the telephonists informed their friends at battalion and company level. "Something's up," they added.

The date was 1st March 1942, General Altrichter, the OC 58th Infantry Division, greeted his officers. They all suspected that their division was to be once again employed on some special mission.

"Bound to be Volkhov," the officers muttered to each other. A fortnight previously Lieutenant Strasser with his 9th Battery, 158th Artillery Regiment, had moved off towards Volkhov together with the Emergency Battalion Lörges as a "ski battery." A week later further batteries had been dispatched towards Novgorod.

Their surmise was quickly confirmed. "Gentlemen," Al-trichter opened the conference, "we have been assigned a task which will have a vital effect on the overall situation."

"Volkhov after all," Colonel Kreipe, commanding 209th Infantry Regiment, said softly to his neighbour, Lieutenant- Colonel Neumann.

General Altrichter had heard him. He nodded and continued: "58th Division has been chosen to be the striking division for sealing off the Volkhov penetration from the south and encircling the enemy forces which have broken through."

Friedrich Altrichter, a doctor of philosophy and the author of interesting essays on military education, formerly on the staff of the Dresden Military College, was good at explaining strategic problems. Many a German officer had passed through his class. He died in Soviet captivity in 1949.

Altrichter stepped up to the large situation map and began his lecture: "You see what the situation is: the enemy has already driven deep into our lines, and in strength. Frontal engagement can no longer lead to success since we don't have the inexhaustible reserves that would be necessary for that kind of operation. Our only chance is to strike at the Russians at the basis of their operation, at the breakthrough point—to pinch them off and thus to isolate the forces which have penetrated. Fortunately, the 126th and 215th Infantry Divisions have once more established firm fronts along the edges of the bottleneck, and we shall be able to assemble under their cover. We shall strike at the gap from the south. The SS Police Division will attack from the north. Rendezvous is the clearing known as Erika. The regiments of 126th Infantry Division and all other formations employed there, including the battalions of the Spanish Blue Division, which have fought splendidly so far, will be subordinated to us. With these forces we should be able to manage it. And we've got to manage it—otherwise Eighteenth Army is lost. But if we succeed in closing the trap, then we shall have the bulk of two Soviet Armies in the bag."

There was silence in the small room. Then a clicking of heels. Outside it was still bitterly cold.

Other books

The Second Confession by Stout, Rex

Death and the Maiden by Gladys Mitchell

Oaxaca Journal by Oliver Sacks, M.D.

Mortal Fall by Christine Carbo

Interview with a Playboy by Kathryn Ross

An Act of Deceit: Book 2 of the Sarah Woods Mysteries by Jennifer L. Jennings

Memnon by Oden, Scott

Honeytrap: Part 3 by Kray, Roberta

Operation Hellfire by Michael G. Thomas