Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (74 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

The main effort was to be made by Dietl's Austrian Mountain Jägers of the 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions. On the day the campaign began they would have to cross the Finnish frontier from Kirkenes in Norway and occupy the Petsamo area. Seven days later "Operation Platinum Fox" was to start —the attack through the tundra against the town and harbour of Murmansk.

It is not known who persuaded Hitler to disregard Dietl's weighty arguments. The only lasting effect they produced was the dispatch of twelve efficient and terribly hardworking detachments of the Reich Labour Service into Dietl's zone of operations. They were the Reich Labour Service groups K363 and K376 under the command of Chief Labour Leader Welser. The courier who brought Dietl Hitler's orders on 7th May also brought with him the necessary maps. On these maps things no longer looked quite so bad. Only a small border strip of the zone of operations was shown as lacking all roads or tracks. A few miles inside the country, however, roads and tracks began to be marked—one from the bridge over the Titovka frontier river over to the Litsa, and another farther south from Lake Chapr to Motovskiy; indeed, from there there was another road running north again to Zapadnaya Litsa. AH these roads connected with the main roads leading into Murmansk. Things were looking more hopeful.

The date was 22no! June. The time was 0200 hours, but the sun, veiled by a light haze, hung over the horizon like a large pale full moon, steeping the country in a watery light. Right across the continent, from the Baltic to the Black Sea 3,000,000 soldiers along a 1250-mile front were waiting at that moment for the order to start a great war. But up north, before Murmansk, under the midnight sun, the element of surprise had to be waived from the start. There was Finnish territory between the German troops' starting-lines in Norway and the Soviet frontier. In Petsamo, moreover, there was a Soviet Consul. He would have noticed any occupation prior to 22nd June and would have alerted Moscow. The surprise element of the whole Operation Barbarossa might have been jeopardized.

For that reason, with the consent of the Finns, a single company of sappers had crossed into Finnish territory during the night of 20th/21st June, in small groups and wearing civilian clothes, in order to prepare for the crossing of the Petsamo river.

In outward appearances the Finns acted most correctly. The Finnish frontier guards waited with bureaucratic pedantry for the hands of their watches to move to 0231 hours eastern time. All right now: the war against Russia had started a minute before. The barrier went up. The men from Styria, the Tyrol, and Salzburg moved off—into their great adventure north of the Arctic Circle.

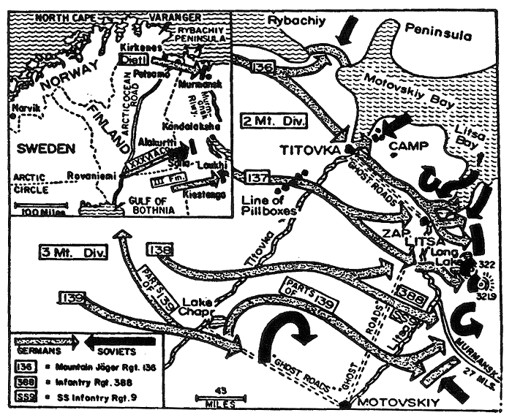

Map 24.

Outline sketch of the front in the Far North and situation map of the operations of 2nd and 3rd Mountain Divisions of the Mountain Corps Norway between 29th June and 18th September 1941.By 24th June the ground had been reconnoitred as far as the frontier. Local Finnish guides conducted the German patrols across rock and scree, over glistening red granite, through streams and snow-drifts.

The first major obstacle was the Titovka, an icy mountain river. Near its estuary, on its eastern bank, close by the little town of the same name, the Soviets had an Army camp with units of a NKVD frontier regiment. Finnish scouts had also established the existence of an airfield.

A particular problem was the Rybachiy Peninsula—or Fishermen's Peninsula. It was not known whether it was held in strength. Major-General Schlemmer was instructed to cut it off quickly at its narrow neck with units of his 2nd Mountain Division, in order to protect the Corps' flank against surprise attack. Simultaneously, battalions of his 136th Mountain Jäger Regiment were to take the Titovka bridge hard by the river's mouth into the fjord.

At first all went well. The 136th sealed off the Rybachiy Peninsula. They captured the bridge and crossed the river. The Army camp and the airfield were deserted. The battalions of the 137th Mountain Jäger Regiment found things more difficult. They came up against a well-prepared Soviet line of defences along the frontiers. Fortunately for them fog descended. While preventing the German artillery and Stukas from supporting the infantry in their attack on the pillboxes, it also enabled them to break through the positions without appreciable casualties. The pillboxes were bypassed, to be subsequently subdued with Stuka and AA gun support.

The resistance offered by the Siberian and Mongolian pillbox crews was a foretaste of what the attackers might come up against later. The defenders did not yield an inch. Even flamethrowers did not induce them to surrender. They fought until they were shot dead, beaten dead, or burnt to death. Only a hundred prisoners were taken.

There was little Soviet air activity. The Russians had left their hundred Rata machines unprotected and uncamouflaged on their two airfields near Murmansk, even after 22nd June. Attacks by a German bomber squadron on the airfields resulted in the destruction of most of the Soviet fighters.

In the evening of 30th June the most forward units of Major-General Schlerrimer's 2nd Mountain Division were on the Litsa river. The regiments of Major-General Kreysing's 3rd Mountain Division laboriously struggled forward past Lake Chapr, looking for the road to Motovskiy which was shown on their map. If all went well they should presently link up with the 1st Company of Major von Burstin's Special Purpose Tank Battalion 40, which was equipped with captured French tanks, and advance to Murmansk along the new Russian road.

But everything did not go well. There was no trace of a road to be found. There was much excitement and to-ing and fro-ing of runners. A signal was sent to Corps headquarters. The Luftwaffe was ordered to investigate. Presently aerial reconnaissance confirmed that there was no road to Motovskiy— not even a track or mule-path. Very soon afterwards 2nd Mountain Division also realized that in its sector there was no road from the Titovka to Zapadnaya Litsa, and no road from there down to Motovskiy.

The German map analysts in the High Command of the Armed Forces had taken the conventional signs to mean the same as they did in Central Europe: they had interpreted the dotted double lines on the Russian maps as tracks. In actual fact these were the routes of telegraph-lines and the approximate movements of the tundra nomads, the Lapps, during the winter.

That was the end of the originally planned employment of the 3rd Mountain Division. Without a road there could be no advance. Admittedly, penetrations of 5 to 10 miles could be made into pathless country if necessary, but it was not possible to hold out, let alone advance, in such country unless cart-tracks were built for the most urgently needed supplies.

Everything therefore had to be regrouped. Without respite, the young Labour Service men, hardly more than boys, were building cart- and mule-tracks,

On 3rd July the 1st Battalion, 137th Mountain Regiment reached the fishing village of Zapadnaya Litsa on the western bank of the Litsa river, just above its estuary. In inflated rubber dinghies the Jägers crossed the river. They came to an abandoned Army camp, where they found hard bread, groats, makhorka tobacco, and, unexpectedly, 150 lorries. There was great astonishment: where there were lorries a road could not be far off. A moment later a great cheer went up.

Down along the valley floor ran a magnificent modern road—the road to Murmansk.

Anxiously the Jägers waited for supplies, for ammunition, for artillery. At last, on 6th July, the attack across the Litsa was mounted on a broad front. The 3rd Mountain Division crossed over in inflated dinghies. The sappers of Lieutenant-Colonel Klatt's Mountain Engineers Battalion 83 tirelessly paddled the dinghies from bank to bank. Now and again they had to pick up their carbines to ward off Russian attacks. The Soviets were shelling the crossing-point. Worse still, they were employing ground-attack aircraft. The German Luftwaffe was absent. The units of Fifth Air Fleet had been withdrawn in order to support the second prong of the attack against Salla and the Murmansk railway 250 miles farther south.

The road to Murmansk was almost within an arm's reach of the 138th Mountain Jäger Regiment. If only they had had a dozen Stukas, a dozen tanks, and some heavy guns they could have burst through the Soviet barrier. But as it was they failed. They were defeated by the terrain: the horse-drawn guns could not get through. The two mountain batteries which had got to the front were down to forty shells. Infantry support did not materialize either. Two-thirds of the division had to be employed on supplies, leaving only one-third to do the fighting. The Russians, on the other hand, brought up their reinforcements in long columns of lorries right to the battlefield. Battalion after battalion was unloaded and deployed for counter-attack to protect the road.

At this tense moment a further piece of alarming news arrived at Dietl's Corps headquarters in Titovka: the Russians were using naval units to land three battalions in the Litsa Bay in the flank and rear of 2nd Mountain Division. The landing was repulsed—but only at the cost of reducing the fighting strength of Major-General Kreysing's Mountain Jäger Regiments, which were by now greatly over-extended.

But the men from Styria and Carinthia did not give in. A flanking attack against the dominating high ground was to gain them breathing-space. With this

tour de force

Dietl wanted to gain access to the road. Meanwhile the German 6th Destroyer Flotilla under Lieutenant-Commander Schulze-Hinrichs was to hold the Soviet forces in the Litsa Bay in check. It was an excellent plan.Detailed orders were sent down from Corps to the regiments. Those for 136th Regiment were carried by the regiment's motor-cycle orderly. But among the rocks and scree he missed regimental headquarters. The German sentry called out after him, yelled, and finally fired his rifle into the air to warn him. It was no use: the noise of the engine drowned it all. At six miles an hour, the dispatch-rider struggled forward until, suddenly, he found himself faced by Russians. He whipped his machine round. One of the Russians fired. The orderly was hit. Three Russians dragged him into a Soviet dugout. The Germans mounted an immediate counter-attack, but it came too late. The orderly and the Russians had gone. The plans for the attack were in Russian hands.

On 13th July Dietl tried another plan. A penetration was made into the Soviet positions, but it was not a break-through. The Soviets just did not budge from the strongly fortified commanding Hills 322 and 321.9 by the "Long Lake." Those infuriating hills were less than a thousand feet high, but the Germans could not take them. They lacked artillery, they lacked dive-bombers, they lacked reserves.

Headquarters personnel, Labour Service men, and the mule attendants worked ceaselessly and practically without sleep. To take one wounded man to the rearward dressing station two relays of four men each were needed, since he had to be carried for up to ten hours. Entire battalions were used up in this way.

In the evening of 17th July Dietl decided with a heavy heart to suspend his attack and go over to the defensive. He was only 28 miles from Murmansk. The chronicler to-day must shake his head in disbelief: why was a job which clearly required a steam-hammer tackled with a bare fist? Dietl, after all, had put Hitler in the picture. And Hitler himself had spoken so heatedly about the importance of Murmansk. Why then was the operation conducted with insufficient weight behind it? Why were three separate sectors of the front attacked with two divisions each, and why was the Luftwaffe switched first one way and then another, instead of all available ground and air forces being concentrated at one focal point?

The answer to the question is that the Finns had miscalculated and had badly advised the Germans. Field-Marshal Mannerheim's High Command had declared that for reasons of terrain it was not possible at any point of the Lapland Front to employ and supply more than two divisions. That had been the reason behind Hitler's plan to attack in three sectors with two divisions each. But the result was that no penetration was made at any of the three sectors.

The two divisions of XXXVI Corps under General of Cavalry Feige, the 169th Infantry Division and the SS Combat Group "North," which mounted their attack 250 miles south of Dietl on 1st July, with the objective of reaching the Murmansk railway at Kandalaksha, admittedly got as far as Ala-kurtti, having fought then- way through Salla, 22 miles from their objective, but at that point their strength gave out, and there they got stuck.

Major-General Siilasvuo's Finnish III Corps with its 6th and 3rd Divisions similarly got no farther than Ukhta and Kestenga, and got stuck about 43 miles from the railway.

Other books

Force Me - Death By Sex by Karland, Marteeka, Azod, Shara

My Point ... And I Do Have One by Ellen DeGeneres

The Giant Among Us by Denning, Troy

The Engagement Game (Engaged to a Billionaire) by Gardner, A.

Marked: A Two Halves Novella by Marta Szemik

How To Bring Your Love Life Back From The Dead by Wendy Sparrow

The Devil Will Come by Justin Gustainis

Garden of Dreams by Melissa Siebert

As It Is in Heaven by Niall Williams