Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (81 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

At that very hour, when Manstein was gazing across to his great objective, 400 miles farther north, in the Kharkov area, the divisions of von Kleist's Army Group were mounting their attack which was to gain them the vital starting-line on the Donets for their summer offensive.

After many sleepless nights and anxious calculations, prompted by a Soviet surprise attack, Colonel-General von- Kleist was now unleashing an offensive which has no parallel in terms of daring arid strategic concept.

"Three o'clock," said Second Lieutenant Teuber, a Company Commander in 466th Infantry Regiment. No one made any reply. What was there to say? After all, it was a statement of fact. It meant that there were another five minutes to go.

In the east the sky was turning red. It was a cloudless sky. There was complete silence—so much so that the men's breathing could be heard. And also the ticking of the second lieutenant's large wrist-watch as he supported his hand against the edge of the trench. The seconds were ticking away —drops of time into the sea of eternity.

At last the moment had come. A roar of thunder filled the ah". To the raw soldiers on the battlefield it was just an unnerving, deafening crash, but the old soldiers of the Eastern Front could make out the dull thuds of the howitzers, the sharp crack of the cannon, and the whine of the infantry pieces.

From the forest in front of them, where the Soviets had their positions, smoke was rising. Fountains of earth spouted into the air, tree-branches sailed up above the shell-bursts— the usual picture of a concentrated artillery bombardment preceding an offensive.

This then was the starting-line of the "Bear" Division from Berlin—but the picture was the same in the sectors held by the regiments of 101st Light Division, the Grenadiers of 16th Panzer Division, and the Jägers of 1st Mountain Division, the spearhead of attack of von Mackensen's III Panzer Corps. Along the entire front between Slavyansk and Lozo-vaya, south of Kharkov, the companies of von Kleist's Army Group were, on that morning of 17th May 1942, standing by to mount their attack under the thunderous roar of the artillery.

At last the barrage in front of the German assault formations performed a visible jump to the north. At the same moment Stukas of IV Air Corps roared over the German lines.

"Forward!" called Second Lieutenant Teuber. And, like him, some 500 lieutenants and second lieutenants were, at that very second, shouting out their command: "Forward!"

The question which had been worrying officers and men during the past few days and hours was forgotten—the great question of whether the German forces would succeed in striking at the root of the Russian offensive that had been moving westward for the past five days.

What was happening on that 17th May? What was the objective of the attack by Kleist's Army Group? To answer this question we must cast our eyes back a little.

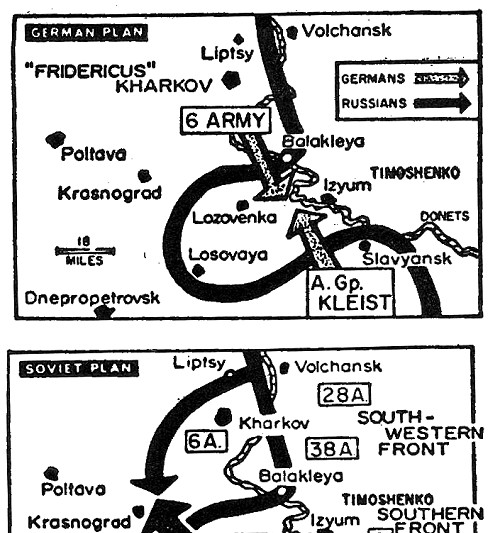

For the purpose of gaining a proper starting-line for the great summer offensive of 1942 from the Kharkov area in the direction of the Caucasus and Stalingrad, Fuehrer Directive No. 41 had ordered that the Soviet bulge on both sides of Izyum, which represented a permanent threat to Kharkov, should be eliminated by a pincer operation. For this operation the C-in-C Army Group South, Field-Marshal von Bock, had made a simple plan: the Sixth Army under General Paulus was to attack from the north, and von Kleist's Group with units of First Panzer Army and Seventeenth Army was to attack from the south. In this way Timoshenko's well-filled bulge was to have been pinched off and the Soviet Armies assembled in it annihilated in a battle of encirclement. The code word for this plan was "Fridericus."

But the Russians too had a plan. Marshal Timoshenko wanted to repeat his January offensive, and therefore he had prepared an attack with even stronger forces, an attack he hoped would decide the outcome of the war. With five Armies and a whole armada of armoured formations he intended to strike from the Izyum bulge and, north of it, from the Volchansk area, where his January offensive had ground to a halt, and burst through the German front with two wedges. In a big outflanking operation the town of Kharkov, the administrative centre of the Ukrainian heavy industry, was to have been retaken. This would have deprived the Germans of their vast supply base for the southern front, a base where enormous stores were situated.

Simultaneously Timoshenko wanted to repeat his earlier attempt of snatching Dnepropetrovsk from the Germans, as well as Zaporozhye, 60 miles farther on, with its huge hydroelectric power station which, in the forties, was a kind of eighth wonder of the world.

The realization of this plan would have been even more disastrous to the German Army Group South than the mere loss of their rearward base of Kharkov. Through Dnepropetrovsk and Zaporozhye ran the roads and railways to the lower reaches of the Dnieper; the river here was more like a string of lakes, and between those towns and the Black Sea there was no further certain crossing over it. All supplies for the German Armies on the southern wing, for the forces east of the Dnieper in the Donets area and in the Crimea, had to pass through these two traffic centres. Their loss would have precipitated disaster.

Thus in the spring of 1942 the attention of both sides was focused on the great bulge of Izyum, the fateful setting of future decisive battles for Bock as well as for Timoshenko. The question was merely: who would strike first, who would win the race against tune—Timoshenko or Bock?

The German time-table envisaged 18th May as the day for the attack, but Timoshenko was quicker.

Map 26.

The great battle south of Kharkov in the early summer of 1942, the curtain-raiser to Operation Blue.

On 12th May he mounted his pincer operation against General Paulus's Sixth Army with surprisingly strong forces. The northern jaw of the pincers, striking from the Volchansk area, was represented by the Soviet Twenty-eighth Army with sixteen rifle and cavalry divisions, three armoured brigades, and two motorized brigades. That was an overwhelming force against two German Corps—General Hollidt's XVII Corps and General von Seydlitz-Kurzbach's LI Army Corps—with altogether six divisions.

Timoshenko's southern jaw struck with even more concentrated power from the Izyum bulge. Two Soviet Armies, the Sixth and the Fifty-seventh, pounced with twenty-six rifle and eighteen cavalry divisions, as well as fourteen armoured brigades, against the positions held by General of Artillery Heitz's VIII Corps and the Rumanian VI Corps, Half a dozen German and Rumanian infantry divisions, initially without a single tank, were finding themselves faced by a vastly superior enemy attacking with colossal armoured support.

There was no hope at all of intercepting the Russian thrust at its two focal points. The German lines were over-run. At the same time, just as during the winter battle, numerous German strongpoints held out in the rear of the advancing enemy.

General Paulus employed all available units of his Sixth Army against the Russian torrent bursting through his lines. Twelve miles before Kharkov he eventually succeeded, literally at the last moment, in halting Timoshenko's northern prong by striking at its flank with the hurriedly brought up 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions and 71st Infantry Division.

But Timoshenko's tremendously strong southern prong, striking from the Izyum bulge, was not to be stopped. Disaster seemed imminent. The Russians pursued their breakthrough far to the west, and on 16th May their cavalry formations were approaching Poltava, Field-Marshal von Bock's headquarters, more than 60 miles west of Kharkov. The situation was becoming dangerous. Bock was faced with a difficult decision.

In two days' time "Fridericus" was due to start. But the Soviet offensive had completely changed the situation. General

Paulus's Sixth Army was pinned down and engaged in desperate defensive fighting. As an offensive striking force it had therefore to be written off. This meant that a pincer operation had become impossible.

Should he therefore drop the whole plan, or should he carry out "Operation Fridericus" with only one jaw? Bock's Chief of Staff, General of Infantry von Sodenstern, was urging him to adopt the "single-prong" solution. In view of the enemy's strength it would be a risky move—but an argument in its favour was the fact that with every mile he advanced farther westward Timoshenko's flank was getting more dangerously exposed.

That was Bock's chance. And in the end the Field-Marshal decided to take it, He decided to carry out "Operation Fridericus" with only one arm. To deny the Russians the possibility of screening their long flank he even advanced the date of attack by one day.

Thus von Kleist's Group—now called an Armeegruppe, or an Army-sized combat group—mounted its attack in the morning of 17th May from the area south of Izyum with units of First Panzer Army and Seventeenth Army. Eight infantry divisions, two Panzer divisions, and one motorized infantry division constituted Kleist's striking force.

Rumanian divisions were covering its left wing.

At 0315 hours Second Lieutenant Teuber leapt out of his trench at the head of his company and with his men charged the Russian positions on the edge of the wood. Stukas screamed overhead, diving and dropping bombs on identified Soviet strongpoints, dugouts, and firing positions.

Some 2-cm. Army anti-aircraft guns on self-propelled carriages were driving along with Teuber's platoons, making up for their lack of tanks. Firing point-blank, these 2-cm. guns of Army Flak Battalion 616 slammed their shells into centres of Soviet resistance. The infantrymen were fond of this weapon and of their fearless crews who invariably rode with them into attack in the foremost line.

The first well-built Soviet positions collapsed under a hail of bombs and shells. Nevertheless those Russians who survived the artillery bombardment offered stubborn resistance. An assault battalion into whose position the 466th Infantry Regiment had driven held out to the last man. Four hundred and fifty killed Russians testified to the ferocity of the fighting.

Only slowly was the regiment able to gain ground through thick undergrowth, through minefields, and over obstacles made from tree-trunks. Second Lieutenant Teuber and his company found themselves up against the particularly stubbornly defended positions of the Mayaki Honey Farm, which was situated a short distance behind the main fighting-line. The Russians were using machine-guns, carbines, and mortars. The company made no headway at all.

"Demand artillery support," Teuber called over to the Artillery Liaison Officer. By walkie-talkie the Liaison Officer sent a message back: "Fire on square 14." A few minutes later a fantastic fireworks display broke out. Russian artillery, in turn, put down a barrage in front of the collective farm.

Teuber and his men charged. Over there was the Russian trench. The Soviets were still in it, cowering against its side. The charging German troops leapt in and likewise ducked close to the wall of the trench, seeking cover from the shells which were dropping in front, behind, and into the trench.

There they were crouching and lying shoulder to shoulder with the Russians. Neither side did anything to fight the other. Each man was clawing himself into the ground. For that moment they were just human beings trying to save themselves from the murderous screaming red-hot splinters of steel. It was as though enmity between man and man had been swept away by the insensate elemental force hammering down upon Russians and Germans.

Other books

The Devil Incarnate (The Devil of Ponong series #2) by Braden, Jill

Ransom by Jon Cleary

Love by Beth Boyd

Hundreds and Thousands by Emily Carr

Sweet Revenge by Katherine Allred

The Secrets of Paradise Bay by Devon Vaughn Archer

Always Mine by Sophia Johnson

Like Jazz by Heather Blackmore

City Lives by Patricia Scanlan

Debra Burroughs - Paradise Valley 02.5 - The Edge of Lies by Debra Burroughs