Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (84 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

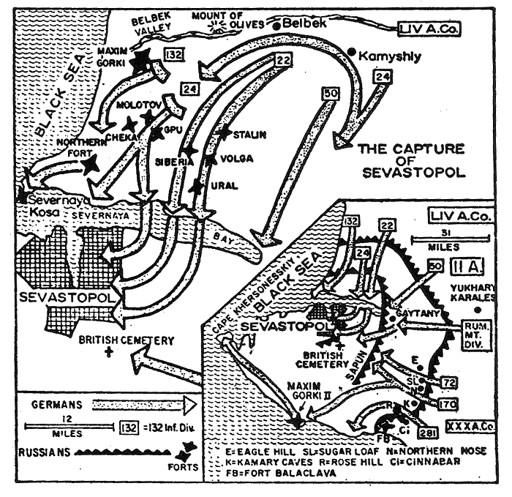

The second belt of defences was about a mile deep and included, especially in its northern sector between the Belbek Valley and Severnaya Bay, a number of extremely heavy fortifications to which the German artillery observers had given easily remembered names—"Stalin," "Molotov," "Volga," "Siberia," "GPU," and—above all—"Maxim Gorky I," with its heavy 12-inch armoured batteries. The companion piece of this fort, "Maxim Gorky II," was south of Sevastopol and similarly equipped.

The eastern front of the fortress was particularly favoured by nature. Difficult country with deep, rocky ravines and fortified mountain-tops provided ideal ground for the defenders. "Eagle's Nest," "Sugar Loaf," "Northern Nose," and "Rose Hill" are the names that will always be remembered by those who fought on the eastern sector of the Sevastopol front.

A third belt of defences ran immediately round the town. This was a veritable labyrinth of trenches, machine-gun posts, mortar positions, and gun batteries.

According to Soviet sources, Sevastopol was defended by seven rifle divisions, one cavalry division on foot, two rifle brigades, three naval brigades, two regiments of marines, as well as an assortment of tank battalions and independent formations—a total of 101,238 men. Ten artillery regiments and two battalions of mortars, an anti-tank regiment and forty-five super-heavy coastal-defence naval gunnery units with altogether 600 guns and 2000 mortars were holding the defensive front. It was truly a fire-belching fortress that Manstein intended to take with his seven German and two Rumanian divisions.

The night of 6th/7th June was hot and sultry. Towards the morning a light sea-breeze sprang up. But it did not carry in any sea air—only dust from the churned-up approaches of Sevastopol. Clouds of this dust and smoke from the blazing ammunition dumps in the southern part of the town were drifting over the German lines.

At daybreak the German artillery bombardment once more stepped up its volume. Then the infantry leapt to their feet. Under this tremendous artillery umbrella assault parties of infantry and sappers charged against the enemy's main fighting-line at 0350 hours.

The main effort was made on the northern front. There the LIV Corps attacked with 22nd, 21st, 50th, and 132nd Infantry Divisions and with the reinforced 213th Infantry Regiment, which belonged to 73rd Infantry Division and formed the Corps reserve.

XXX Corps attacked from the west and south. But all that was not yet the main drive. The 72nd Infantry Division, the 28th Light Infantry Division, and the 170th Infantry Division, together with the Rumanian formations, were merely to gain a starting-line for the main attack scheduled for a few days later.

Up in the Belbek Valley and the Kamyshly Ravine the sappers were clearing lanes through the minefields, to enable the assault guns of Battalions 190 and 249 to be employed as quickly as possible in support of the infantry. Meanwhile the infantrymen were contending for the first enemy field positions. Although the artillery had smashed trenches and dugouts, the surviving Russians were resisting desperately. They had to be driven out of their well-camouflaged firing- pits with hand-grenades and smoke canisters,

Major-General Wolff's 22nd Infantry Division from Lower Saxony was once again assigned the difficult task of seizing Fort Stalin. During the previous winter the assault companies of 16th Infantry Regiment had scaled the outer ramparts of the fortress, but had then been compelled to withdraw again and had been taken back to the Belbek Valley.

Now they were to travel that costly road once more. Their first attempt, on 9th June, misfired. On 13th June the 16th, under the command of Colonel von Choltitz, again attacked the fort. Fort Stalin was a heap of shattered masonry, but fire was still coming from all directions. In the Andreyev wing the fortress commandant had employed only Komsomol and Communist Party members. In the operations report of the 22nd Infantry Division we read: "This was probably the toughest opponent we ever encountered."

Ta quote just one of many examples. Thirty men had been killed in one pillbox which had received a direct hit against its firing-slit. Nevertheless the ten survivors fought like demons.

They had piled up their comrades' dead bodies like sandbags behind the shattered embrasures.

Map 27.

The capture of Sevastopol. After five days of "annihilation bombardment" by artillery and Luftwaffe, Eleventh Army on 7th June 1942 launched its attack on the world's strongest fortress. The last fort fell on 3rd July 1942.

"Sappers forward!" the infantrymen shouted. Flame-throwers directed their jets of fire against this horrible barricade. Hand-grenades were flung. Some German troops were seen vomiting. But not until the afternoon did four Russians, trembling and utterly finished, reel out of the wreckage. They gave up after their political officer had shot himself.

The two attacking battalions of 16th Infantry Regiment suffered heavily in this savage fighting. Before long all their officers had fallen. A second lieutenant from the "Leaders' Reserve" took over command of the remnants of the rifle

companies of the two battalions.

The fierce fighting for the second belt of defences raged in a sweltering heal: until 17th June. An unbearable stench hung over the battlefield, which was covered with countless bodies over which flies buzzed in great clouds. The Bavarian 132nd Infantry Division on the right of the Lower Saxons had suffered such heavy casualties that it had to be temporarily withdrawn from the line. Its place was taken by the 24th Infantry Division, which—relieved in turn by the Rumanian 4th Mountain Division—was inserted between the 132nd and 22nd Infantry Divisions.

The situation was far from rosy for the German formations. Casualties were mounting ever higher, and an acute shortage of ammunition made it necessary from time to time to call a halt in the fighting. Already some commanding officers were suggesting that the attack should be suspended until new forces had been brought up. But Manstein knew very well that he could not count on any reinforcements.

On 17th June he gave orders for a renewed general attack along the entire northern front. The battered regiments once again went into action, firmly determined to take the main obstacles this time.

In the Belbek Valley, two and a half miles west of the "Mount of Olives," two 14-inch mortars were being moved into position. They belonged to the heavy motorized Army Artillery Battalion 641, and their instructions were to smash the armoured cupolas of "Maxim Gorky I." This Soviet fort's 12-inch shells were controlling the Belbek Valley and the way down to the coast.

It was a terrible job to get the two giants into firing position. After four hours of hard work by a construction party the battery commander. Lieutenant von Chadim, was at last able to give his first firing orders.

With a thunderous roar the monsters came to life. After the third salvo Sergeant Meyer, who was lying as the forward observer in the foremost line of 213th Infantry Regiment, reported that the hits scored by the concrete-piercing missiles had so far produced no effect on the armoured cupola.

"Special Röchling bombs," Chadim commanded. The nearly 12-feet-long projectiles, weighing one ton each, were handled into position with the aid of cranes. The "Röchlings" had already proved their value in the Western campaign, against the fortifications of Liège. They exploded not on impact, but only after they had penetrated some way into the resisting target.

Sergeant Friedel Förster and his fourteen comrades at No. 1 gun clapped their palms over their ears as the lieutenant raised his arm. "Fire!"

Twenty minutes later the operation was repeated. "Fire!"

Shortly afterwards came Sergeant Meyer's signal: "Armoured cupola blown off its hinges!"

"Maxim Gorky" had had its head cracked. The barrels of its 12-inch naval guns could be seen pointing at an angle at the sky. The battery was silent.

Now was the moment for Colonel Hitzfeld, the conqueror of the Tartar Ditch of Kerch. At the head of the battalions of his 213th Regiment he charged against the fort and occupied the armoured turrets and approaches.

"Maxim Gorky I" was no longer able to fire. But the Soviet defenders inside the vast chunk of concrete, which was over 300 yards long and 40 yards wide, did not surrender. Indeed, groups of them even staged lightning-like sorties through secret exits and ventilation-shafts.

The second company of Engineers Battalion 24 was ordered to put an end to the opposition. Demands for surrender were answered by the Soviets with machine-pistol fire. The first major blasting operation was staged with a mountain of dynamite, incendiary oil, and smoke canisters. When the fumes and smoke had dispersed the Soviets were still firing from embrasures and openings.

The second blasting eventually tore the concrete block wide open. Its vast interior was revealed to the sappers. "Maxim Gorky I" was three storeys deep—a veritable town.

The fort had its own water and power supply, a field hospital, canteen, engineering shops, ammunition lifts, arsenals, and deep battle stations. Every room and every corridor was protected by double steel doors. Each of these had to be blasted open individually.

The sappers flattened themselves against the walls. When the steel doors burst they flung their hand-grenades into the smoke and waited for the fumes to disperse. Then they went on to the next door.

The corridors were littered with Soviet dead. They looked like monsters, since they all wore gas-masks. The smoke and the stench had made this necessary.

In the next corridor the Germans suddenly came under machine-pistol fire. Hand-grenades were flung; pistol-shots rang out. Then a steel door slammed. The savage game started anew. Thus it went on hour after hour, as the fighting approached the nerve centre of the fortress—the command post.

The fighting in the fort "Maxim Gorky" was closely followed also in Sevastopol, in the battle headquarters of

Vice-Admiral Oktyabrskiy, near the harbour. The wireless officer, Lieutenant Kuznetsov, was sitting at his receiver in the wireless-room listening. Every thirty minutes a report came through from "Maxim Gorky" on the situation. The Admiral's order to all commanders and commissars had been: "Resistance to the last man."

There was the signal. Kuznetsov listened and took it down: "There are forty-six of us left. The Germans are hammering at our armoured doors and calling on us to surrender. We have opened the inspection hatch twice to fire at them. Now this is no longer possible."

Thirty minutes later came the last signal: "There are twenty-two of us left. We're getting ready to blow ourselves up. No more messages will be sent. Farewell."

They were as good as their word. The brain centre of the fort was blown up by its surviving defenders. The battle was over. Of the fort's complement of 1000 only fifty men were taken prisoners, and they were wounded. This figure speaks for itself.

On 17th June, while the battle for "Maxim Gorky I" was still raging, the Saxon battalions of 31st Infantry Regiment, 24th Infantry Division, took the forts "GPU," "Molotov," and "Cheka."

Major-General Wolff's 22nd Infantry Division from Bremen likewise made some headway towards the south, on the left of the Saxons, and on 17th June, with 65th Infantry Regiment, reinforced by 2nd Battery Assault Gun Battalion 190, took the fort "Siberia." The 16th Infantry Regiment cracked the forts "Volga" and "Ural." The 22nd were the first to reach Severnaya Bay on 19th June—the last barrier to the north of the southern part of Sevastopol.

Major-General Friedrich Schmidt's 50th Infantry Division from Brandenburg and Mecklenburg, together with General Laszar's Rumanian 4th Mountain Division, had the thankless task of making their way laboriously through the shrub- grown, rocky terrain from the north-east towards the high ground of Gaytany. They succeeded, and thus reached the eastern corner of Severnaya Bay.

Other books

Chasing Superwoman by Susan DiMickele

Spider Wars: Book Three of the Black Bead Chronicles by J.D. Lakey

Acts of God by Mary Morris

The Heat Is On by Katie Rose

I Hadn't Understood (9781609458980) by De Silva, Diego

Classics Mutilated by Conner, Jeff

A History of Zionism by Walter Laqueur

Stoking the Embers (New Adult Romantic Suspense): The Complete Series by Johnson, Leslie

Twisted by Rebecca Zanetti

Six Month Rule (Kingston Ale House) by A.J. Pine