Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (86 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

Consequently, a certain element of doubt continues to attach to the incident to this day.

For the German Command at the end of June 1942 it was, of course, of decisive importance to know whether Reichel was dead or whether he was alive in Russian captivity. If he was dead, then the Russians could know only what they had found on his map and in the typed note—the first phase of "Operation Blue." If they had caught the major alive, then there was the danger that GPU specialists would make him reveal all he knew. And Reichel, naturally, knew very nearly everything, in broad outline, about the grand plan for the offensive. He knew that it aimed at the Caucasus and at Stalingrad. The idea that the Soviet secret service had got Reichel and might make him talk did not bear thinking about. Yet there was every ground for suspecting that just that had happened.

It was no secret that Soviet front-line troops had strict orders to handle any officer with crimson stripes down his trousers—

i.e.,

every General Staff officer—like a piece of china and to take him at once to the next higher headquarters. Any German General Staff officers killed in action had to be brought in if at all possible, because in this way the Germans would be kept guessing uneasily whether they were alive or not. This uncertainty was deliberately fomented by skilful front-line propaganda.Why should the Soviets suddenly make an exception? And even if they did, why the burial?

There is only one logical solution to the mystery. Reichel and his pilot had been taken prisoners by a Soviet patrol and subsequently killed. When the leader of the patrol brought the map and the briefcase to his commander the latter must have realized at once that this had been a senior German staff officer. To avoid unpleasantness and any possible questions about the bodies, he had sent the patrol back with orders to bury the two officers they had killed.

Needless to say, Stumme had to report the Reichel incident to Army at once. Lieutenant-Colonel Franz had already made a telephonic report during the night of 19th/20th June towards 0100 hours, to the thief of staff of Sixth Army, Colonel Arthur Schmidt, subsequently Lieutenant-General Schmidt. And General of Panzer Troops Paulus had no other choice but to report the matter, though with a heavy heart, via Army Group to the Fuehrer's Headquarters in Rastenburg.

Fortunately Hitler was just then in Berchtesgaden, and the report did not come to his ears straight away. Field-Marshal Keitel was in charge of the initial investigations. He was inclined to recommend to Hitler to take the severest measures against "the officers culpable as accomplices."

Keitel of course guessed Hitler's reaction. The Fuehrer's order had laid it down quite clearly that senior staffs must pass on operational plans only by word of mouth. In his Directive No. 41 Hitler had once again laid down strict security regulations for that vital operation, "Operation Blue." Hitler was constantly afraid of spies, and on every possible occasion had emphasized the principle that no person must know more than was absolutely necessary for the discharge of his task.

General Stumme, together with his chief of staff, Lieutenant-Colonel Franz, and General von Boineburg-Lengsfeld, the

commander of 23rd Panzer Division, were relieved of their posts three days before the offensive, and Stumme and Franz were tried by a Special Senate of the Reich Military Court. Reich Marshal Goering presided. The indictment consisted of two charges—premature and excessive disclosure of orders.

In a twelve-hour hearing Stumme and Franz were able to prove that there could be no question of a "premature" issuing of orders. Moving the Panzer Corps into the Vol-chansk bridgehead over the only available Donets bridge alone required five of the short June nights. That left the charge of "excessive disclosure of orders," and this became the core of the prosecution's case. It was pointed out that Corps had warned its Panzer divisions that, after crossing the Oskol and turning northward, they might encounter Hungarian formations in khaki uniforms similar to the Russian ones. This warning had been necessary since there was a danger that the German Panzer formations might otherwise mistake the Hungarians for Russians.

But the tribunal did not accept this excuse. The two defendants were sentenced to five and two years' fortress detention respectively. True, at the end of the hearing, Goering went and shook hands with both prisoners and said, "You argued your case honestly, courageously, and without subterfuge. I shall say so in my report to the Fuehrer."

Goering seems to have kept his promise. Field-Marshal von Bock likewise put in a good word for the two officers in a personal conversation with Hitler at the Fuehrer's Headquarters. Whose intervention it was that softened Hitler's heart it is impossible to establish to-day. But after four weeks Stumme and Franz were informed in identical letters that in view of their past services and their outstanding bravery the Fuehrer had remitted their sentences. Stumme went to Africa as Rommel's deputy, and Franz followed him as chief of staff of the Afrika Corps. On 24th October General Stumme was killed in action at El Alamein. He lies buried there.

Following Stumme'is recall, the XL Corps was taken over by General of Panzer Troops Leo Freiherr Geyr von Schwep-penburg, the successful commander of XXIV Panzer Corps. He inherited a difficult task.

There was no doubt left: by 21st June, at the latest, the Soviet High Command knew the plan and order of battle for the first phase of the great German offensive. It was also known at the Kremlin that the Germans intended to make a direct west-east thrust from the Kursk area with extremely strong forces, and to gain Voronezh in an outflanking move by Sixth Army from the Kharkov area, in order thus to annihilate the Soviet forces before Voronezh in a pocket between Oskol and Don.

What the Soviets were not able to see from the map and piece of paper which the unfortunate Reichet had had with him was the fact that Weichs' Army Group was subsequently to drive south and southeast along the Don, and that the great strategic objectives were Stalingrad and the Caucasus Unless, of course, Reichel had after all been taken alive by the Russians, and grilled, and the body in the grave by the aircraft had been some one else's.

Considering the cunning of the Soviet Intelligence Service, this possibility could not be entirely ruled out. The question, therefore, which the Fuehrer's Headquarters had to answer was: Should the plan of operation and the starting date be upset?

Both Field-Marshal von Bock and General Paulus opposed this suggestion. The deadline for the offensive was imminent, which meant that it was too late for the Soviets to do very much about countering the German plans. Moreover, General Mackensen had mounted his second "trail-blazing operation" on 22nd June, and, with the objective of gaining a suitable starting-line for Sixth Army, had fought a successful minor battle of encirclement together with units of First Panzer Army in the Kupyansk area, resulting in the taking of 24,000 prisoners and the gaining of ground across the Donets to the Lower Oskol.

The launching platforms for "Operation Blue" had thus been gained. To interfere now with the complicated machinery of the great plan would mean to jeopardize everything. The machine, once started and so far running smoothly, must be allowed to run on. Hitler therefore decided to mount the offensive as envisaged: D-Day for Weichs' Army Group on the northern wing was 28th June, and for Sixth Army with XXL Panzer Corps it was 30th June. The die was cast.

What followed is closely connected with the tragic affair of Major Reiche! and contains the seed of the German disaster in Russia. It marks the beginning of a string of strategic mistakes which led inescapably to the disaster of

Stalingrad, to the turning-point of the war in the East, and hence to Germany's defeat. To understand this turning- point, this change of fortunes which struck the German Armies in the East so suddenly, at the very peak of their success, it is necessary to look more closely at the involved strategic moves of "Operation Blue."

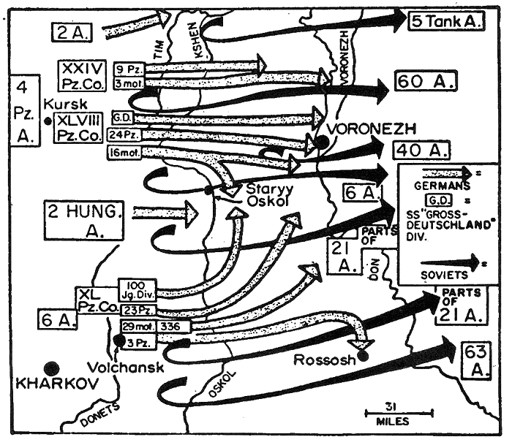

The basis of phase one of the German offensive in the summer of 1942 was the capture of Voronezh. This town, situated on two rivers, was an important economic and armaments centre, and controlled both the Don, with its numerous crossings, and the smaller Voronezh river. The town, moreover, was a traffic junction for all central Russian north-south communications, by road, rail, and river, from Moscow to the Black Sea and the Caspian. In "Operation Blue" Voronezh figured as the pivot point for movements to the south, and as a support base for flank cover.

On 28th June von Weichs' Army Group launched its drive against Voronezh with Second Army, the Hungarian Second Army, and the Fourth Panzer Army, Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army acting as the main striking force. Its core, in turn, its battering-ram as it were, was XLVIII Panzer Corps under General of Panzer Troops Kempf with 24th Panzer Division in the middle and 16th Motorized Infantry Division and the "Grossdeutschland" Division on the right and left respectively.

The 24th Panzer Division—formerly the East Prussian 1st Cavalry Division and the only cavalry division in the Wehrmacht to be re-equipped as a Panzer division during the winter of 1941-42—was assigned the task of taking Voronezh.

The division, under Major-General Ritter von Hauenschild, struck with all its might. Under cover of fire provided by VIII Air Corps the Soviet defences were over-run, the Tim river was reached, the bridge across it stormed, and the fuse, already lit for the demolition of the bridge, ripped out just in time. Then the divisional commander raced across in his armoured infantry carrier, ahead of the reinforced Panzer Regiment.

With the dash of cavalry the tanks raced down towards the Kshen river. Artillery and transport columns of the Soviet 160th and 6th Rifle Divisions were smashed. Another bridge was seized intact. It was a headlong chase. Divisional commander and headquarters group were right in front, regardless of exposed flanks, in accordance with Guderian's motto: "An armoured force is led from in front and is in the happy position of always having exposed flanks."

Whenever a refuelling halt had to be made the force was regrouped and quickly assembled combat groups raced on. By the evening of the first day of the attack motor-cyclists and units of 3rd Battalion, 24th Panzer Regiment, were charging the village of Yefrosinovka.

"Well, well, what have we got here?" Captain Eichhorn said to himself. On the edge of the village was a veritable forest of signposts, as well as radio vans, headquarters baggage trains, and lorries. This must be a senior command.

The motor-cyclists narrowly missed making a really big catch: the headquarters staff of the Soviet Fortieth Army, which had been stationed there, escaped at the last minute. But although they got away, their Army with the dispersal of its headquarters had lost its head.

In this fashion 24th Panzer Division, in the scorching summer of 1942, revived once more those classic armoured thrusts of the first few weeks of the war, and thereby demonstrated what a well-equipped, fresh, and vigorously led Panzer division was still capable of accomplishing against the Russians. Only a cloudburst stopped the confident formations for a while. They formed 'hedgehogs,' waited for the Grenadier regiments to follow up, and then the spearheads drove on under Colonel Riebel.

Map 28.

The opening move of Operation Blue (28th June-4th July 1942). Voronezh was to be taken, and the first pocket to be formed in the Staryy Oskol area in co-operation between Fourth Panzer Army and Sixth Army. But for the first time the Soviet Armies refused battle and swiftly moved back across the Don.By 30th June the 24th Panzer Division had covered half the distance to Voronezh. It was facing a well-prepared Soviet position held by four rifle brigades. Behind them two armoured brigades were identified. Things were getting serious.

The Soviets employed three armoured Corps in their attempt to encircle the German formations which had broken through, and to cover Voronezh. Lieutenant-General Fedor-enko, Deputy Defence Commissar and Commander-in- Chief of Armoured Troops, personally took charge of the operation. Clearly the Russians were aware of the significance of the German drive on Voronezh.

But Fedorenko was unlucky. His grandly conceived armoured thrust against the spearhead of Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army proved a failure. Superior German tactics, extensive reconnaissance, and a more elastic form of command ensured victory over the more powerful Soviet T-34 and KV tanks.

On 30th June, also, the day when 24th Panzer Division went into its first great tank battle, the German Sixth Army, 90 miles farther south, launched its drive towards the northeast, with Voronezh as its objective. The great pincers were being got ready to draw Stalin's first tooth. The operation was supported from the air by IV Air Corps, under Air Force

Other books

Black Flagged Apex by Konkoly, Steven

The Darkest Surrender by Gena Showalter

Lucky Stars by Kristen Ashley

Camp Wild by Pam Withers

Killing The Blood Cleaner by Hewitt, Davis

Douglass’ Women by Rhodes, Jewell Parker

Feuding Hearts by Natasha Deen

Last Chance Hero by Cathleen Armstrong

Razor's Edge: Men in Blue, Book 2 by Jayne Rylon

Trouble Brewing by Dolores Gordon-Smith