Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 (90 page)

Read Hitler Moves East, 1941-1943 Online

Authors: Paul Carell

- Simultaneously another force, to be composed of fast formations, will take the area around Groznyy, with some of its units cutting the Ossetian and Georgian Military Highways, if possible in the passes. Subsequently this force will drive along the Caspian to take possession of the area of Baku. . . .

The Italian Alpini Corps will be assigned to the Army Group at a later date.

This operation of Army Group A will be known under the code name "Edelweiss."

- Army Group B—as previously instructed—will, in addition to organizing the defence of the Don line, advance against Stalingrad, smash the enemy grouping which is being built up there, occupy the "city itself, and block the strip of land between Don and Volga.

As soon as this is accomplished fast formations will be employed along the Volga with the object of driving ahead as far as Astrakhan in order to cut the main arm of the Volga there too.

These operations of Army Group B will be known by the code name of "Heron."

This was followed by directives for the Luftwaffe and the Navy.

Field-Marshal List, a native of Oberkirch in Bavaria, a man with an old Bavarian General Staff training and with distinguished service in the campaigns in Poland and France, was the General Officer Commanding Group A. He was a clever, cool, and sound strategist—not an impulsive charger at closed doors, but a man who believed in sound planning and leadership and detested all military gambles.

When a special courier handed him Directive No. 45 at Stalino on 25th July, List shook his head. Subsequently, in captivity, he once remarked to a small circle of friends that only his conviction that the Supreme Command must have exceptional and reliable information about the enemy's situation had made the new plan of operations seem at all comprehensible to him and his chief of staff, General von Greif-fenberg.

Always form strongpoints—that had been the main lesson of Clausewitz's military teaching. But here this lesson was being spectacularly disregarded. To quote just one instance: moving up behind Sixth Army, which was advancing towards Stalingrad and the Volga valley, were formations of the reinforced Italian Alpini Corps with its excellent mountain divisions. List's Army Group A, on the other hand, which was now faced with the first real alpine operation of the war in the East—the conquest of the Caucasus—had at its disposal only three mountain divisions, two of them German and one Rumanian. The Jäger divisions of Ruoff's Army-sized combat group (the reinforced Seventeenth Army) were neither trained for alpine warfare nor did they possess the requisite clothing and equipment. Four German mountain divisions— hand-picked men from the Alpine areas and thoroughly trained in mountain warfare—were employed piecemeal all over the place. A few weeks later, when it was too late, the Fuehrer's Headquarters was to be painfully reminded of that fact when General Konrad's Mountain Jäger battalion found themselves pinned down along the ridges of the Caucasus, within sight of their objective.

Allowing for the forces at his disposal, Field-Marshal List turned Directive No. 45 into a passable plan of operations. Ruoff's group, the reinforced Seventeenth Army, was to strike south frontally from the Rostov area towards Krasnodar. The fast troops of Kleist's First Panzer Army—followed on their left wing by Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army—were given the task of bursting out of their Don bridgeheads and driving on Maykop as the outer prong of a pincer movement. In this way, by the collaboration between Ruoff's slower infantry divisions and Kleist's fast troops, the enemy forces presumed to be south of Rostov were to be encircled and destroyed.

Colonel-General Hoth's Fourth Panzer Army on the eastern wing was to provide flank cover for this operation. Its first objective was Voroshilovsk.

[Now Stavropol.]

This then was the plan for the attack towards the south, for an operation which followed a highly dramatic course and proved decisive for the whole outcome of the war in the East.

While Ruoff's group was still fighting for Rostov some of the units of the First and Fourth Panzer Armies had advanced as far as the Don. By 20th July the Motor-cycle Battalion of 23rd Panzer Division had succeeded in crossing the river at Nikolayevskaya and establishing a bridgehead on the southern bank of the Don. Three days later a combat group of 3rd Panzer Division thrust south and crossed the Sal at Orlovka. From there the XL Panzer Corps drove against the Manych sector with 3rd and 23rd Panzer Divisions.

The Soviet Command was clearly determined not to allow its forces to be encircled again. The Soviet General Staff and the commanders in the field stuck strictly to their new strategy—essentially the old strategy that had defeated Napoleon —of enticing the enemy into the wide-open spaces of their vast country in order to make him fritter away his strength until they could pounce upon him on a broad front at the right moment.

The German formations encountered entirely novel combat conditions south of the Don. Ahead of them lay 300 miles of steppe, and beyond it one of the mightiest mountain ranges in the world, extending from the Black Sea to the Caspian, right across the path of the attacking German armies.

The steppe north of the Caucasus provided the enemy with excellent opportunities for elastic resistance. The countless water-courses, big and small, running from the watershed of the Caucasus towards the Caspian as well as towards the Black Sea, were obstacles which could be held by defenders with relatively slight forces.

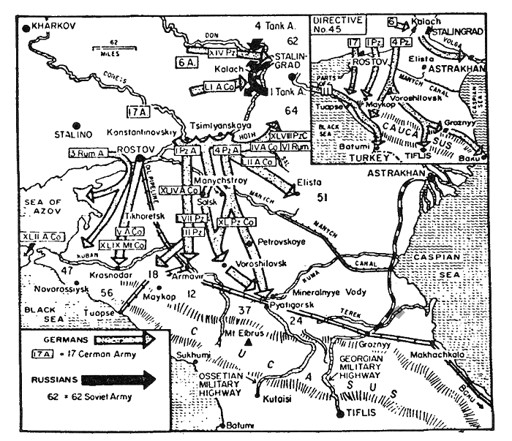

Map 29.

The situation on the southern front between 25th July and early August 1942. The inset map shows the position envisaged in Directive No. 45.As in the desert, the route of advance through the steppe was dictated to the attacker by watering-points. The war was moving into a strange and unfamiliar world. The more than 400-mile-long Manych, eventually, formed the boundary between Europe and Asia: to cross it meant to leave Europe.

The Westphalian 16th Motorized Infantry Division of the III Panzer Corps and the Berlin-Brandenburg 3rd Panzer Division of XL Panzer Corps were the first German formations to cross into the Asian continent.

General Breith's 3rd Panzer Division, the spearhead of XL Panzer Corps, had pursued the retreating Russians from the Don over the Sal as far as Proletarskaya on the Karycheplak, a tributary of the Manych. Breith's Panzer troops had thus reached the bank of the wide Manych river. Strictly speaking, this river was a string of reservoirs backed up by dams; these lakes were often nearly a mile wide. The reservoirs and massive dams formed a hydroelectric power system known as Manych-Stroy.

On the far bank, well dug in, were the Soviet rearguards. The Manych was an ideal line of defence for the Soviets, a solid barrier across the approaches to the Caucasus.

"How are we going to get across there?" General Breith anxiously inquired of his chief of operations, Major Pom-tow,

and of the commander of 3rd Rifle Regiment, Lieutenant-Colonel Zimmermann.

"Where the river is narrowest the Russian defences are strongest," replied Pomtow, pointing to a file of aerial reconnaissance reports.

"According to prisoners' evidence, the far bank is held by NKVD troops," Zimmermann added. "And well dug in, too, by the look of these aerial pictures," Breith nodded.

"Why not outwit them by choosing the widest spot—near the big dam, where the river is nearly two miles across? They won't expect an attack there," Pomtow suggested.

It was a good idea, and it was adopted. Fortunately, the Panzer Engineers Battalion 39 was still dragging twenty-one assault boats with them. They were brought up. The scorching heat had so desiccated them that, when they were tried out, two of the boats sank like stones at once. The other nineteen were also leaky, but would be all right provided the men baled vigorously.

Second Lieutenant Moewis and a dozen fearless "Brandenburgers" reconnoitred two suitable crossing-points, almost exactly at the widest point of the river. Both crossings were upstream from the small town of Manych-Stroy, which was situated directly at the far end of the dam. The dam itself appeared to have been blocked and mined in a few places only. The small town would have to be taken by surprise, so as to prevent any Soviet demolition parties from wrecking the dam completely.

For this action a combat group was formed from units of 3rd Panzer Grenadier Brigade. The 2nd Battalion, 3rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, attacked on the left and the 1st Battalion on the right. A strong assault company was formed from units of 2nd Battalion, 3rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, and put under the command of First Lieutenant Tank, the well- tried commander of 6th Company. Its orders were: "Under cover of darkness a bridgehead will be formed on the far bank of the reservoir. Following the crossing by all parts of the combat group, the enemy's picket line will be breached and the locality of Manych-Stroy taken by storm."

To ensure effective artillery support from the north-eastern bank an artillery observer was attached to the combat group. The bold attack by XL Panzer Corps across the Manych was successful. At the focal point of the action 3rd Panzer Division feinted an attack from the north-west with one battalion of 6th Panzer Regiment, while the 1st Battalion, 3rd Panzer Grenadier Regiment, actually struck across the river. The action was prepared by a sudden concentrated bombardment by divisional artillery between 2400 and 0100 hours.

Tank's men were lying on the bank. The sappers had pushed their craft into the water. The shells were whining overhead, crashing on the far bank and enveloping it in smoke and dust.

"Now!" ordered Tank. They leapt into the boats and pushed off. They had to bale feverishly with empty food-tins to prevent the boats being flooded. The noise of the motors was drowned by the artillery bombardment. Not a shot was fired by the Russians.

The river was crossed without casualties. The keels of the nineteen boats scraped over the gravel on the far bank. Tank was the first to leap ashore. He was standing in Asia.

"White Very light," Tank called out to the squad commander. The white flare soared skyward from his pistol. Abruptly the German artillery lengthened range. The sappers got into their boats again to bring over the next wave.

Tank's men raced over the flat bank. The Soviets in the first trench were completely taken by surprise and fled. Before they could raise the alarm in the next trench Tank's machine-guns were already mowing down the enemy's outposts and sentries.

But by then the Russians to the right and left of the landing-point had been alerted. When the assault craft came over with their second load they were caught in the crossfire of Soviet machine-guns. Two boats sank. The remaining

seventeen got across, with 120 men and supplies of ammunition, as well as the 2nd Battalion headquarters.

But that was the end of the ferrying. Major Boehm, the battalion commander, succeeded in extending the bridgehead on the southern bank of the Manych. Then he was severely wounded. Lieutenant Tank, the senior company commander in 2nd Battalion, assumed command in the bridgehead. The Russians were covering the entire bank with enfilading fire. Soviet artillery of all calibres pounded the area. In any case, with increasing daylight all further ferrying operations had to come to an end.

Lieutenant Tank and his men were still lying on the flat ground by the river, in the captured Soviet trenches and in hurriedly dug firing-pits. The Russians were mortaring and machine-gunning them, and also launched two counterattacks which got within a few yards of Tank's position.

The worst of it was that they were running out of ammunition. The machine-gun on the right wing had only two belts left. Things were not much better with the others. The mortars had used up all their ammunition.

"Why isn't the Luftwaffe showing up?" Tank's men were asking as they looked at the hazy, overcast sky. Towards 0600 hours, almost as if the commodore commanding the bomber Geschwader had heard their prayers, German fighter-bombers roared in, just as the sun was breaking through, the sun which a short while earlier had dispersed the fog from their airstips. They shot up the Soviet artillery emplacements and machine-gun nests. Under cover of the hail of bombs and machine-gun fire a third wave of infantry was eventually ferried across the river.

Lieutenant Tank made good use of their waiting time. He skipped from one platoon commander to another, instructing them in detail. Then the attack was launched, platoon by platoon—against Manych-Stroy.

- Simultaneously another force, to be composed of fast formations, will take the area around Groznyy, with some of its units cutting the Ossetian and Georgian Military Highways, if possible in the passes. Subsequently this force will drive along the Caspian to take possession of the area of Baku. . . .

Other books

Deadly Reunion (The Taci Andrews Deadly Series) by Manemann, Amy

The Soldiers of Wrath MC 1 Owned by the Bastard by Jenika Snow, Sam Crescent

Tip and the Gipper: When Politics Worked by Chris Matthews

First Kiss (Emma's Arabian Nights, #1) by Mayburn, Ann

Lost Nation by Jeffrey Lent

Chance Assassin: A Story of Love, Luck, and Murder by Nicole Castle

Her Soldier (That Girl #3) by H. J. Bellus

Don't Read in the Closet volume one by various authors

Drama Queen by Chloe Rayban

The Gingerbread Boy by Lori Lapekes